Common lenders in emerging Asia: their changing roles in three crises

The "common lender channel" is a mechanism that facilitates the spread of financial shocks around the globe. Creditor banks withdraw from previously unaffected countries when highly exposed to the epicentre of a crisis. At the time of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, Japanese banks dominated lending to emerging Asia. When Japanese banks cut their credit sharply, less exposed European banks took over as leading lenders. When the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09 and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2010 struck, it was euro area lenders' turn to pull back from Asia owing to their extensive exposures. By contrast, less exposed Japanese banks expanded their lending. Today, Chinese banks have a sizeable and growing global footprint. In the face of future shocks at home or abroad, they are likely to take their turn as important common lenders.

JEL classification: F34, F36, G21.1

Several recent financial crises have exhibited a common lender channel. This is the tendency for crisis conditions to spread from one country to another as creditor banks pull back from previously unaffected countries because of a shock they have suffered in a crisis-hit country.

The common lender channel played an especially important role in the Asian financial crisis (AFC) of 1997-98, when a series of countries suffered severe financial stress with significant real consequences. In this highlights feature, we analyse the ebb and flow of international bank credit in emerging Asia around the time of the AFC as well as around the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-09 and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12. The composition of creditor banks in the region has changed in important ways over the past two decades (McGuire and van Rixtel (2012)). These episodes thus present three different patterns of lending countries' exposures to crisis-stricken countries, and three different examples of how the common lender channel can affect credit to emerging market economies (EMEs).

After briefly setting out the concepts underlying the common lending channel, we explore how this channel operated in emerging Asia during the three crisis episodes. The AFC stands as a polar case, featuring shocks to both the demand and the supply of credit. The GFC gives a mixed picture. The demand for credit within Asia hardly changed, while the supply effects differed across creditor banks. During the European sovereign debt crisis, demand effects in Asia were also mild, while supply effects again paint a more nuanced picture. Finally, we examine the current composition of lenders in the region, including the growing global footprint of Chinese banks.

Lenders and borrowers in emerging Asia

The common lender channel

When several countries borrow from just a few big international banks, these borrowers face the risk of what is called the "common lender channel". Unexpected losses in one country may induce banks to withdraw from other borrower countries as banks restructure their asset portfolio in an attempt to rebalance overall risks and satisfy regulatory constraints (Kaminsky and Reinhart (1999)). Contagious spillovers can thereby spread the turmoil around the globe. Researchers have tended to lay particular emphasis on the transmission of shocks emanating from the common lenders' home countries.

The rich dimensionality structure of the BIS international banking statistics allows us to examine more complex relationships involving several borrower and lender countries. For example, we can look at how shocks in a given borrower country might affect how exposed banks in a lending country choose to alter their lending to other, unaffected countries. This allows us to study how the dynamics of the common lender channel play out across different relative exposures of the creditor banks.

The borrowers

The two decades since the AFC have seen a broad rise in international credit to EME borrowers in Asia. According to the BIS locational banking statistics,2 cross-border claims of BIS reporting banks more than quadrupled, totalling $2 trillion in 2017. Among the Asian EMEs, we restrict our focus to Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, the countries at the epicentre of the AFC. We will refer to them as "emerging Asia". Together, these five countries accounted for 69% of the region's total cross-border credit in Q2 1997, and 24% in Q3 2017. The considerable decline in their regional share reflects the emergence of China as the largest borrower in the region from BIS reporting banks.

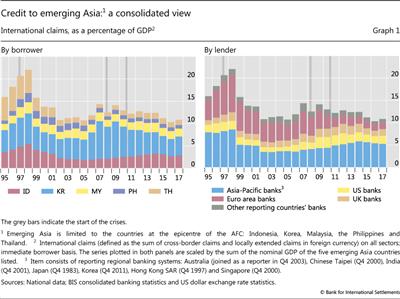

When taking local positions in foreign currency into account, consolidated3 international claims4 on emerging Asia reached 21% of these borrowers' combined GDP on the eve of the AFC in mid-1997. In absolute amounts international credit has risen by two thirds over the past 20 years, while relative to GDP it has ebbed and flowed (Graph 1, left-hand panel). As of Q3 2017, international claims of creditors reporting to the BIS consolidated banking statistics fell to 11% of emerging Asia's GDP, suggesting that the sensitivity of these countries to a sudden withdrawal by international lenders has declined over the past two decades. It should be noted that these data do not include credit granted by banks headquartered in countries that do not report to the BIS consolidated banking statistics, even if the claims have been intermediated through BIS reporting locations.

The lenders

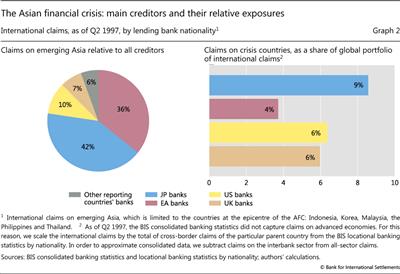

Different countries and regions have taken turns as home to the leading bank lenders to emerging Asia (Graph 1, right-hand panel). Exactly whose turn it was depended on the adjustments made in response to each successive crisis. Japanese banks assumed the role of leading lenders in 1997, reporting about 42% of all international consolidated claims5 on the five AFC countries we focus on (Graph 2, left-hand panel). Slightly behind them, euro area banks held 36%, with German and French banks accounting for the bulk thereof and UK banks for 7%.

In the aftermath of the AFC, the dominance of Japanese banks was increasingly challenged by European banks. By mid-2008, Japanese banks held 15% of international claims, while euro area (35%) and UK (14%) banks jointly held almost half of all claims. The changes in the composition of the lenders within the Asia-Pacific region itself were also significant. Banks headquartered in Australia, Hong Kong SAR and Singapore accounted for about 11% of all regional claims.6

With the onset of the European sovereign debt crisis in 2010, other banks from the Asia-Pacific region found opportunities to make inroads. As of end-2010, the combined share of Japanese banks plus regional banks from offshore centres and EMEs in Asia accounted for almost 32% of all international claims. By that time, the shares of euro area and UK banks amounted to 24% and 15%, respectively.

Incomplete data and changing reporting standards of the consolidated banking statistics make it difficult to track all lenders over time. Hence, we limit our analysis of the three crisis episodes to the roles of the major global banks headquartered in the euro area, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. It should also be noted that in what follows, reflecting the structure of the BIS banking statistics, we look at borrowing and lending exposures at the level of national banking systems rather than that of individual banks. There was of course significant variation across banks, including banks from the same country, in how they adjusted their borrowing and lending positions throughout this period.

The Asian financial crisis

The AFC was triggered by speculative attacks in July 1997 on the currencies of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand.7 These four countries saw sharp currency depreciations, losses of foreign exchange reserves and stock market collapses. In November, the crisis spread to Korea. What made this crisis so severe, among other factors, was the contagion that ensued (Glick and Rose (1999)). Shifts in investor sentiment also contributed to these contagion effects (Cohen and Remolona (2008a)).

The five crisis-hit countries had borrowed most heavily from Japanese banks. These creditor banks, in turn, were significantly exposed to the epicentre of the crisis. On the eve of the AFC, borrowers in emerging Asia owed 42% of their international bank debt to Japan (Graph 2, left-hand panel). The five crisis-stricken countries had also borrowed heavily from euro area banks, which held 36% of the claims. Banks from the United States and the United Kingdom accounted for 10% and 7% of international credit to emerging Asia, respectively. Japanese claims on emerging Asia represented 9% of their global portfolio (Graph 2, right-hand panel). This was higher than the 6% ratio reported by US and UK banks, respectively, and the 4% ratio reported by euro area banks.

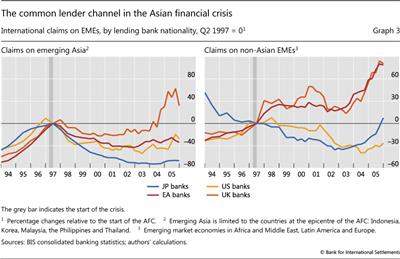

The crisis came at a particularly unfortunate time for Japanese banks. In 1997, these banks were still struggling from the effects of the end-1980s Japanese financial bubble, which left them with a large stock of weak or non-performing domestic corporate and real estate loans (Ueda (2000)). Hence, they were not in a good position to bear additional losses. As McCauley and Yeaple (1994) pointed out, even before the crisis Japanese banks had changed course, making room for other banks, especially in the interbank market. Reflecting this, the pace of Japanese banks' expansion in the five crisis countries slowed relative to that of other global lenders (Graph 3, left-hand panel). With the onset of the crisis, lending by Japanese banks to emerging Asia fell by up to 72% over seven years. Japanese banks also cut the credit they provided to other EMEs, such as those in Africa and the Middle East, Latin America and Europe, by up to 36% as of Q3 2002 (right-hand panel, blue line). While Japanese banks' credit to emerging Asia started to recover only in 2004, their lending to other EMEs reached pre-crisis levels in 2005. The pattern of Japanese banks' lending to non-Asian EMEs in the aftermath of the AFC thus points to the presence of spillover effects as described by the common lender channel.

The adjustment patterns to the AFC exhibited by other major lenders differ substantially, but were in general not as sharp as in the case of Japanese banks. Lending by US banks to emerging Asia also dropped by about 50% over the six years following the AFC (Graph 3, yellow lines). However, in contrast to Japanese banks, their international lending to other EMEs after 1997 remained almost unchanged initially, although they tended to reduce their EME credit significantly after 2001. Euro area banks' lending to emerging Asia declined by up to 43% by end-2002, but started to rebound in 2003 (red lines). Despite their more severe exposure to the crisis-hit borrowers, UK banks actually withdrew the least and had fully recovered by 2004 (orange lines). In contrast to their US and Japanese counterparts, euro area and UK banks never cut their exposure to other EMEs in the wake of the AFC, and in fact increased it, especially from 2003 onwards.

As a result of these shifts, the composition of creditor banks in emerging Asia changed fundamentally in the decade following the AFC. Euro area and UK banks made inroads in this market, and US banks partly followed suit. By contrast, Japanese banks lost market share. In June 2008, on the eve of the GFC, the leading bank creditors of emerging Asia were now the banks from Europe. Banks from the euro area and the United Kingdom jointly held almost 50% of the international consolidated claims on the five Asian countries, while Japanese banks accounted for only 15%.

The Great Financial Crisis

Triggered by defaults in subprime mortgages in the United States, the GFC was amplified by runs in the US repo market and defaults on collateralised debt obligations (Cohen and Remolona (2008b)). In August 2008, the interbank market in Europe froze and the ECB had to step in and provide liquidity. In September, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual collapsed and a number of other institutions were absorbed by competitors or received aid from the official sector. The crisis was centred on the United States, but affected global banks worldwide. For many non-US banks, the crisis manifested itself partly in the form of a dollar shortage that was related to problems in the interbank market (McGuire and von Peter (2009)).

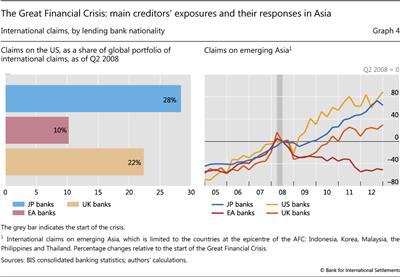

In contrast to the AFC, the top lenders to emerging Asia ahead of the GFC were not at the same time the most exposed lenders to the epicentre of the crisis, the United States. Japanese banks reported the highest overall exposure, with 28% of their international assets being invested in the US. For UK banks, borrowers in the US accounted for 22% of their international claims; for euro area banks, only 10% (Graph 4, left-hand panel). Once we take into account the claims in local currency of these banks' US-based affiliates, the exposure of Japanese creditor banks to the United States rises to 32% of their global portfolio, while that of UK and euro area banks climbs to 30% and 15%, respectively.8

However, some banks' positions led to higher losses than others'. European banks' exposures were heavily tilted towards assets that immediately suffered when the US subprime bubble burst. By contrast, the exposure of Japanese banks to US borrowers was concentrated in safe assets such as US Treasury securities. As argued by Amiti et al (2017), Japanese banks had never succumbed to the structured finance boom. Between 2002 and 2007, they were busy restructuring their balance sheets after taking huge write-offs in the early 2000s.9

Facing large and growing losses on their US exposures, euro area and UK banks cut back on their lending to Asian borrowers, again reflecting the common lender channel at work. Over two quarters, UK banks' international credit to emerging Asia saw a decline of about 32%. However, it bounced back in early 2009 and returned to its 2008 level in mid-2010 (Graph 4, right-hand panel). Banks from the euro area also withdrew from emerging Asia. Within three quarters, their outstanding claims fell by 29%, and then remained relatively constant until the outbreak of the European sovereign debt crisis.

By contrast, Japanese creditor banks barely reduced their lending to emerging Asia. As one of the few major banking systems with sufficiently sound balance sheets, they actually expanded internationally. Within a year and a half, these banks' claims were back to where they had stood in mid-2008 and had started growing strongly (Graph 4, right-hand panel).

As in 1997, the composition of creditor banks lending to emerging Asia changed in the aftermath of the crisis. While European banks remained the leading lenders to emerging Asia, their position was not as dominant as before. At the end of 2010, European creditors (comprising euro area and UK banks) jointly accounted for slightly less than 40% of all international claims on emerging Asia. Japanese and US banks remained important creditors, with market shares of roughly 20% each.

The European sovereign debt crisis

Compared with the Asian crisis, the European sovereign debt crisis was a slow-burner. Greece lost its access to the bond market in May 2010, but at first other European countries were not affected. Ireland would lose market access in November 2010 and Portugal in April 2011. Eventually, Italy and Spain would also face difficulties in raising funds. For our purposes, we date the start of the crisis to the last quarter of 2010. The choice of the precise start date does not affect our findings.

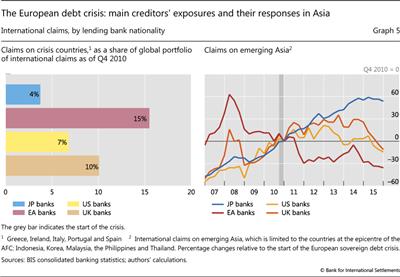

In terms of exposures to the crisis countries - which we define as Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain - euro area banks obviously stand out. Their claims on these five crisis countries made up 15% of all their international claims (Graph 5, left-hand panel). UK and US creditor banks were also quite exposed, with a share of 10% and 7%, respectively. Much less exposed this time were Japanese banks, with a ratio of only 4%.

Credit adjustment patterns in emerging Asia in response to the shock from Europe again point to the presence of a common lender channel. The most exposed banks withdrew, while the less exposed banks stepped in. With the epicentre of the crisis so far away, emerging Asia was unlikely to see a strong contraction of its own demand for credit. Instead, any declines in credit flows are likely to have been due to supply side effects triggered by the common lender channel.

Just as Japanese banks with significant exposures in their home region had cut back on lending elsewhere during the AFC, euro area banks cut their lending to distant borrowers in EMEs the most. Claims held by euro area banks fell by about 30% within one year (Graph 5, right-hand panel).

At the same time, claims held by other major banking systems on emerging Asia grew. UK banks' lending surged initially by around 20% and then stayed above its pre-crisis level for about five years. While Japanese banks' claims on emerging Asia rose rather steadily, by about two thirds over two years, US banks' lending turned out to be more volatile over the same period.

Where emerging Asia finds itself today

At first sight, the common lender risks that emerging Asia faces today seem much less worrisome than before. Relative to regional GDP, emerging Asia is now borrowing much less internationally than it did two decades ago. In 1997, international consolidated claims of BIS reporting banks on the five Asian borrower countries we focus on reached 21% of their total GDP. As of the third quarter of 2017, such claims had shrunk to merely 11% (Graph 1).

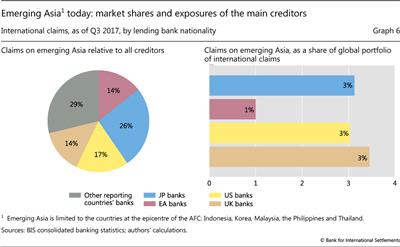

In terms of exposures, traditional creditors' claims on emerging Asia have dropped significantly as a share of their global portfolios over the past two decades. As of Q3 2017, international claims on emerging Asia represented about 3% for banks from the UK, the US and Japan, respectively (Graph 6, right-hand panel). In the case of Japanese banks, this share declined to a mere third of its 1997 level; for US and UK banks, it essentially halved. Over the same period, euro area banks cut their exposure from 4% to 1%.

Moreover, emerging Asia seems to be borrowing from a more diversified set of lenders whose market shares have become more evenly distributed. The region still relies on Japan for about a quarter of its international borrowing (Graph 6, left-hand panel). However, about 17% of international claims are held by US banks, while the euro area and the United Kingdom remain important creditors, with market shares of roughly 14% each.

The reduction in shares held by traditional lenders has been mirrored by a rise in the share of banks from "Other reporting" countries. As Remolona and Shim (2015) point out, the push for regional bank integration by the member countries of ASEAN is likely to lead to even greater intraregional lending. McGuire and van Rixtel (2012) also argue that Chinese banks located in offshore centres like Hong Kong SAR contribute significantly to these new lenders' international credit business in emerging Asia.

Chinese banks have become an increasingly important provider of international bank credit, to borrowers both within and outside Asia. At the moment, China does not report consolidated banking claims. Relying only on the BIS locational data by nationality, which it does report, gives an incomplete picture of the banks' global footprint. Nonetheless, based on the BIS locational banking statistics as of Q3 2017, with cross-border financial assets worth about $2.0 trillion, Chinese banks now rank as the sixth largest international creditor group worldwide. As pointed out by Hu and Wooldridge (2016), Chinese banks are net creditors in the international banking system. Further, when lending abroad, Chinese banks do so largely in US dollars. In absolute terms, Chinese banks are now the third largest provider of US dollars to the international banking system.

Looking forward, the common lender channel would pose its greatest risk to emerging Asia if the shock were to come from Asian borrowers themselves, as it did during the AFC, and if the largest lenders to the region were at the same time highly exposed to the region relative to their broader global portfolios. Among all banks headquartered in advanced economies, Japanese banks do still loom large in terms of these exposures. Over time, however, as the new group of Asian lenders continues to expand both their lending to the region and their global footprint in EMEs, the common lender channel may start to reassert itself through this new group of creditors as a potential mechanism of contagion.

Conclusions

Like in a game of musical chairs, the banks that have dominated the business of lending to emerging Asia have been changing places over the last two decades. Changes in the composition of bank creditors alter how contagion effects from the common lender channel play out during a crisis.

We find that spillovers from the common lender channel have played a role in shaping international banking flows to emerging Asia and the composition of creditor banks in the region over the last 20 years. Empirical evidence suggests that this channel was a source of contagion during the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis, particularly with respect to lending to EMEs outside the Asian region. During the Great Financial Crisis a decade later, euro area banks' toxic exposure to the United States induced them to pull back from lending to Asia. The European sovereign debt crisis of 2010 reinforced their retreat.

Recent years have seen a return of regional banking in Asia. Japanese banks have become significant players again, but they do not dominate this lending business to the same extent as they did before 1997. Now, another major group of lenders from the region has emerged. This group includes Chinese banks and possibly other banks located, but not headquartered, in the offshore centres of Hong Kong and Singapore. Most likely, these new lenders will continue to expand in the future.

In the face of shocks, Chinese banks have the potential to play an important role as common lenders. As the sixth largest group of international creditors worldwide, their global footprint encompasses not just emerging market economies, but also advanced economies and offshore centres worldwide.

References

Amiti, M, P McGuire and D Weinstein (2017): "Supply- and demand-side factors in global banking", BIS Working Papers, no 639, May.

Cohen, B and E Remolona (2008a): "Information flows during the Asian crisis: evidence from closed-end funds", Journal of International Money and Finance, vol 27, pp 636-53.

--- (2008b): "The unfolding turmoil of 2007-2008: lessons and responses", in P Bloxham and C Kent (eds), Lessons from the financial turmoil of 2007-2008, Reserve Bank of Australia.

Glick, R and A Rose (1999): "Contagion and trade: why are currency crises regional?", Journal of International Money and Finance, vol 8, pp 603-17.

Hu, H and P Wooldridge (2016): "International business of banks in China", BIS Quarterly Review, June, pp 7-8.

Kaminsky, G and C Reinhart (1999): "The twin crises: the causes of banking and balance-of-payment problems", American Economic Review, vol 89, no 3, pp 473-500.

McCauley, R and S Yeaple (1994): "How lower Japanese asset prices affect Pacific financial markets", Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Review, Spring, pp 19-33.

McGuire, P (2002): "Japanese bank reform: bold ideas tempered", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 5-6.

McGuire, P and A van Rixtel (2012): "Shifting credit patterns in emerging Asia", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 17-8.

McGuire, P and G von Peter (2009): "The dollar shortage in global banking and the international policy response", BIS Working Papers, no 291, October.

Moreno, R, G Pasadilla and E Remolona (1998): "Asia's financial crisis: lessons and policy responses", Asian Development Bank Institute.

Remolona, E and I Shim (2015): "The rise of regional banking in Asia and the Pacific", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 119-34.

Ueda, K (2000): "Causes of Japan's banking problems in the 1990s", in T Hoshi and H Patrick (eds), Crisis and change in the Japanese financial system, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp 59-81.

1 We thank Stefan Avdjiev, Claudio Borio, Stijn Claessens, Benjamin Cohen, Robert McCauley, Patrick McGuire, Swapan-Kumar Pradhan, Hyun Song Shin and Philip Wooldridge for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Zuzana Filková and José María Vidal Pastor for excellent statistical assistance. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the BIS.

2 The locational banking statistics are structured according to the location of banking offices and capture the activity of all internationally active banking offices in the reporting country regardless of the nationality of the parent bank. Banks record their positions on an unconsolidated basis, including those vis-à-vis their own offices in other countries.

3 The consolidated banking statistics are structured according to the nationality of reporting banks and are reported on a worldwide consolidated basis, ie excluding positions between affiliates of the same banking group. Banks consolidate their inter-office positions and report only their claims on unrelated borrowers.

4 International bank claims are the sum of banks' cross-border claims and their local claims denominated in foreign currencies.

5 In fact, as of 1997 Japan was the only country in the region reporting consolidated data.

6 In addition, some loans to emerging Asia were extended by banks that did not report to the BIS banking statistics, as their headquarters were located outside the BIS reporting countries. McGuire and van Rixtel (2012) suggest that these were mainly Chinese banks located in Asian offshore centres. In the current setup, this part of credit to emerging Asia falls outside the scope of our analysis.

7 See Moreno et al (1998) for a review.

8 In the BIS international banking statistics, this broader aggregate is labelled "foreign claims". This category comprises cross-border claims and local claims, where local claims refer to credit extended by foreign banks' affiliates located in the same country as the borrower.

9 For a discussion of Japanese bank reforms, see McGuire (2002).