International liquidity standards and banks' demand for central bank reserves

Box extracted from chapter "Monetary policy operational frameworks – a new taxonomy"

International prudential standards that strengthen banks' liquidity management could in principle interact with the implementation of monetary policy by affecting the demand for reserves – the liquid asset par excellence.  This box conceptually reviews whether the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) or other prudential standards may give rise to such interactions.

This box conceptually reviews whether the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) or other prudential standards may give rise to such interactions. The review shows that Basel III does not impose any explicit regulatory requirements on reserve holdings but does create scope for supervisors to do so. By affecting cost-benefit trade-offs, prudential standards could also generate incentives for banks to hold more reserves. The materiality of the various effects hinges on the monetary policy operational framework.

The review shows that Basel III does not impose any explicit regulatory requirements on reserve holdings but does create scope for supervisors to do so. By affecting cost-benefit trade-offs, prudential standards could also generate incentives for banks to hold more reserves. The materiality of the various effects hinges on the monetary policy operational framework.

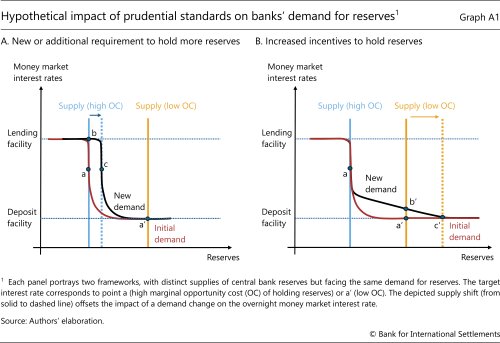

The operational framework determines which part of the demand for reserves is relevant. Banks' demand decreases with the difference between the overnight money market rate and the rate at the central bank deposit facility – that is, with the marginal opportunity cost of holding an additional unit of reserves (see the stylised example in Graph A1). Under a prototypical framework with a high opportunity cost, the quantity demanded is low, reflecting mostly what banks need to hold (eg for payment purposes or to meet requirements): the blue supply curves cross the steep part of the demand curve. Under a low-opportunity cost framework, by contrast, the supply (green line) crosses the flat part of the demand curve at a high level of reserves that banks choose to hold in view of the relative returns on similar assets. Importantly, the different parts of the demand for reserves would respond differently to prudential requirements and to stronger incentives to hold reserves.

Under a low-opportunity cost framework, by contrast, the supply (green line) crosses the flat part of the demand curve at a high level of reserves that banks choose to hold in view of the relative returns on similar assets. Importantly, the different parts of the demand for reserves would respond differently to prudential requirements and to stronger incentives to hold reserves.

A prudential requirement would create interest-insensitive demand for reserves, shifting the curve outward (Graph A1.A). The resulting impact on the overnight interest rate would be stronger, all else being equal, under frameworks imposing a high opportunity cost (a rise from point a to b). This creates a greater need for countervailing central bank actions – an increase in the supply of reserves – to ensure interest rate control (at point c). Conceptually, the demand and supply adjustments would resemble those under standard central bank reserve requirements.

Standards that increase the regulatory or supervisory benefits of holding a certain level of reserves – but do not impose requirements – would have different implications. Such standards would be inconsequential either at a high opportunity cost that dwarfs the new benefits or when banks already hold the amount necessary to achieve these benefits. In intermediate cases, however, the incentives stemming from the standards would raise the demand for reserves (Graph A1.B). This would prompt the central bank to pre-empt an interest rate rise (from point a' to b') by supplying more reserves (at point c'), thus ensuring interest rate control.

The above conceptual considerations notwithstanding, the LCR and NSFR are not designed to affect the demand for reserves. Neither formulates an explicit requirement for reserve holdings. Further, the LCR treats equally reserves and other Level 1 high-quality liquid assets (HQLA), eg domestic sovereign bonds. While the NSFR in principle treats reserves slightly more favourably than other Level 1 HQLA, many jurisdictions eliminate this difference. Thus, in practice, these two standards also do not alter banks' incentives to hold reserves.

Thus, in practice, these two standards also do not alter banks' incentives to hold reserves.

That said, the Basel III liquidity standards create scope for supervisors to influence the demand for reserves. For instance, the standards prescribe monetisation tests that guide supervisory assessments of banks' ability to liquidate non-reserve HQLA in private markets. Stricter assumptions about market conditions and more dire consequences of failing these tests strengthen banks' incentives to hold reserves, as they help to reduce market liquidity risks and operational limitations. As further similar examples, intraday liquidity considerations or supervisory stress tests that impose losses on non-reserve HQLA could incentivise banks to increase their reserve holdings. In extreme cases, a conservative implementation of the standards or stringent supervisory actions could create interest-insensitive demand for reserves – similar to the effect of a requirement.

As further similar examples, intraday liquidity considerations or supervisory stress tests that impose losses on non-reserve HQLA could incentivise banks to increase their reserve holdings. In extreme cases, a conservative implementation of the standards or stringent supervisory actions could create interest-insensitive demand for reserves – similar to the effect of a requirement.

Factors other than Basel III liquidity standards could also influence banks' incentives to hold central bank reserves. For instance, stricter margining requirements that seek to reduce settlement risk may increase banks' need for central banks reserves in times of market volatility. The anticipation of such needs could lead to a higher precautionary demand for reserves in frameworks with low marginal costs of holding them.

The anticipation of such needs could lead to a higher precautionary demand for reserves in frameworks with low marginal costs of holding them.

Proper assessment of the above mechanisms' quantitative implications for the conduct of monetary policy requires empirical analysis, which is beyond the scope of this box. Importantly, only unpredictable shifts in the demand for reserves could interfere with interest rate control – eg shifts in response to margin calls triggered by a sudden spike in market volatility – as the central bank may be able to address them only with a lag. By contrast, as the monopoly supplier of reserves, a central bank can pre-empt any undesirable effect of predictable demand shifts on the overnight interest rate.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS or its member central banks.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS or its member central banks.  The LCR seeks to ensure that banks maintain sufficient high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to cover net cash outflows over a 30-day stress scenario. The NSFR requires banks to maintain a stable funding profile to reduce reliance on short-term wholesale funding. See also Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), Principles for sound liquidity risk management and supervision, September 2008.

The LCR seeks to ensure that banks maintain sufficient high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to cover net cash outflows over a 30-day stress scenario. The NSFR requires banks to maintain a stable funding profile to reduce reliance on short-term wholesale funding. See also Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), Principles for sound liquidity risk management and supervision, September 2008.  The picture is more complex under an archetypal tiering framework, which is not covered in this box.

The picture is more complex under an archetypal tiering framework, which is not covered in this box.  Minimum reserve requirements are imposed by central banks for liquidity management and monetary policy reasons in many jurisdictions.

Minimum reserve requirements are imposed by central banks for liquidity management and monetary policy reasons in many jurisdictions.  While Basel III sets the stable funding requirement for non-reserve Level 1 HQLA at 5% and for reserves and cash at 0% (see NSFR 30.25 and 30.26), many jurisdictions apply a uniform 0% funding requirement (see eg BCBS, Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP) Assessment of Basel NSFR regulations – European Union, June 2022; or BCBS, RCAP Assessment of Basel NSFR regulations – United States, July 2023.

While Basel III sets the stable funding requirement for non-reserve Level 1 HQLA at 5% and for reserves and cash at 0% (see NSFR 30.25 and 30.26), many jurisdictions apply a uniform 0% funding requirement (see eg BCBS, Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP) Assessment of Basel NSFR regulations – European Union, June 2022; or BCBS, RCAP Assessment of Basel NSFR regulations – United States, July 2023.  The LCR standard requires banks to periodically monetise a representative proportion of the assets to test market access, monetisation processes and collateral availability (see LCR 30.15).

The LCR standard requires banks to periodically monetise a representative proportion of the assets to test market access, monetisation processes and collateral availability (see LCR 30.15).  For example, in response to the March 2020 jump in margin requirements, central bank reserves became a more important source of liquidity in both absolute and relative terms (see BCBS-Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures-International Organization of Securities Commissions, Review of margining practices, 2022).

For example, in response to the March 2020 jump in margin requirements, central bank reserves became a more important source of liquidity in both absolute and relative terms (see BCBS-Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures-International Organization of Securities Commissions, Review of margining practices, 2022).