Towards resilient growth

Abstract

Over the past year, the global economy has strengthened further. Growth has approached long-term averages, unemployment rates have fallen towards pre-crisis levels and inflation rates have edged closer to central bank objectives. With nearterm prospects the best in a long time, this year's Annual Report examines four risks that could threaten the sustainability of the expansion in the medium term: a rise in inflation; financial stress as financial cycles mature; weaker consumption and investment, mainly under the weight of debt; and a rise in protectionism. To a large extent, these risks are rooted in the "risky trinity" highlighted in last year's Annual Report: unusually low productivity growth, unusually high debt levels, and unusually limited room for policy manoeuvre. Thus, the most promising policy strategy is to take advantage of the prevailing tailwinds to build greater economic resilience, nationally and globally. Raising the economy's growth potential is critical. At the national level, this means rebalancing policy towards structural reforms, relieving an overburdened monetary policy, and implementing holistic frameworks that tackle the financial cycle more systematically. At the global level, it means reinforcing the multilateral approach to policy - the only one capable of addressing the common challenges the world is facing.

Full text

What a difference a year can make in the global economy, in terms of both facts and, above all, sentiment. The facts paint a brighter picture. There are clear signs that growth has gathered momentum. Economic slack in the major economies has diminished further; indeed, in some of them unemployment rates have fallen back to levels consistent with full employment. Inflation readings have moved closer to central bank objectives, and deflation risks no longer figure in economic projections. But sentiment has swung even more than facts. Gloom has given way to confidence. We noted last year that conditions were not as dire as typically portrayed. Now, concerns about secular stagnation have receded: all the talk has been about a revival of animal spirits and reflation on the back of buoyant financial markets. And with the outcome of the US presidential election as a turning point, political events have taken over from central bank pronouncements as the main financial market driver.

Yet, despite the best near-term prospects for a long time, paradoxes and tensions abound. Financial market volatility has plummeted even as indicators of policy uncertainty have surged. Stock markets have been buoyant, but bond yields have not risen commensurately. And globalisation, a powerful engine of world growth, has slowed and come under a protectionist threat.

Against this backdrop, the main theme of this year's Annual Report is the sustainability of the current expansion. What are the medium-term risks? What should policy do about them? And, can we take advantage of the opportunities that a stronger economy offers?

The Report evaluates four risks - geopolitical ones aside - that could undermine the sustainability of the upswing. First, a significant rise in inflation could choke the expansion by forcing central banks to tighten policy more than expected. This typical postwar scenario moved into focus last year, even in the absence of any evidence of a resurgence of inflation. Second, and less appreciated, serious financial stress could materialise as financial cycles mature if their contraction phase were to turn into a more serious bust. This is what happened most spectacularly with the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Third, short of serious financial stress, consumption might weaken under the weight of debt, and investment might fail to take over as the main growth engine. There is evidence that consumption-led growth is less durable, not least because it fails to generate sufficient increases in productive capital. Finally, a rise in protectionism could challenge the open global economic order. History shows that trade tensions can sap the global economy's strength.

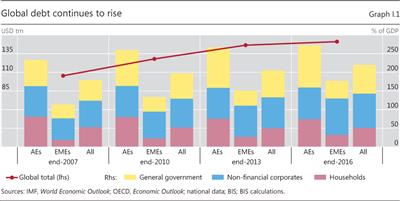

These risks may appear independent, but they are not. For instance, policy tightening to contain an inflation spurt could trigger, or amplify, a financial bust in the more vulnerable countries. This would be especially true if higher policy rates coincided with a snapback in bond yields and US dollar appreciation: the strong post-crisis expansion of dollar-denominated debt has raised vulnerabilities, particularly in some emerging market economies (EMEs). Indeed, an overarching issue is the global economy's sensitivity to higher interest rates given the continued accumulation of debt in relation to GDP, complicating the policy normalisation process (Graph I.1). As another example, a withdrawal into trade protectionism could spark financial strains and make higher inflation more likely. And the emergence of systemic financial strains yet again, or simply much slower growth, could heighten the protectionist threat beyond critical levels.

Some of these risks have roots in developments that have unfolded over decades, but they have all been profoundly shaped by the GFC and the unbalanced policy response. Hence the "risky trinity" highlighted in last year's Annual Report: unusually low productivity growth, unusually high debt levels, and unusually limited room for policy manoeuvre. 1

Given the risks ahead, the most promising policy strategy is to take advantage of the prevailing tailwinds to build greater economic resilience, nationally and globally. At the national level, this means rebalancing policy towards structural reforms, relieving an overburdened monetary policy, and implementing holistic policy frameworks that tackle more systematically the financial cycle - a medium-term phenomenon that has been a key source of vulnerabilities. Raising the economy's growth potential is critical. At the global level, it means reinforcing the multilateral approach to policy - the only one capable of addressing the common challenges the world is facing.

In the rest of this introductory chapter, we briefly review the year in retrospect before analysing the medium-term risks to the sustainability of the expansion. We conclude with an exploration of policy options.

The year in retrospect

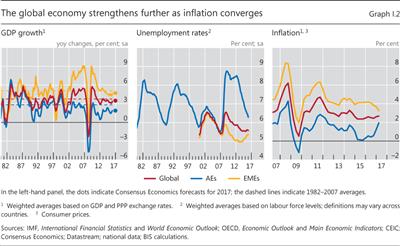

Global growth has strengthened considerably since the release of last year's Annual Report, beating expectations (Chapter III and Graph I.2, left-hand panel). Growth is now projected to reach 3.5% in 2017 (consensus forecast). This rate would be in line with the long-term historical average, although below the close to 4% experienced during the pre-crisis "golden decade". The pickup was especially marked in advanced economies, where, going into 2017, confidence indicators had reached readings not seen in years. Growth was more mixed in EMEs, although there too performance improved, buoyed by higher commodity prices. In particular, the feared sharp slowdown in China did not materialise, as the authorities stepped in once more to support the economy, albeit at the cost of a further expansion in debt.

The maturing economic recovery absorbed economic slack further, especially in labour markets (Chapter III and Graph I.2, centre panel). Unemployment rates in major advanced economies continued to decline. In some that had been at the core of the GFC, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, unemployment returned to pre-crisis levels; in others, such as Japan, it was well below. While still comparatively high, unemployment also ebbed further in the euro area, reaching levels last seen some eight years ago.

Inflation, on balance, moved closer to central bank objectives (Chapter IV and Graph I.2, right-hand panel). Boosted to a considerable extent by higher oil prices, headline rates in several advanced economies rose somewhat; core rates remained more subdued. Inflation actually decreased in some EMEs where it had been above target, not least as a result of exchange rate movements. Consensus forecasts for 2017 point to a moderate increase globally.

The change in financial market sentiment was remarkable (Chapter II). In the wake of the US election, after a short-lived fall, markets rebounded, as concerns about a future of slow growth gave way to renewed optimism. Subsequently comforted by better data releases, the "reflation trade" lingered on in the following months. Equity markets soared and volatilities sank to very low levels, indicative of high risk appetite. The increase in bond yields that had started in July accelerated. On balance, however, bond yields still hovered within historically low ranges, and by May 2017 they had reversed a significant part of the increase, when the reflation trade faded. The US dollar followed an even more see-saw pattern, surging until early 2017 and then retracing its gains.

Equally remarkable was the shift in the main forces driving markets (Chapter II). Politics, notably the UK vote to leave the European Union (Brexit) and above all the US election, took over from central banks. Correspondingly, the "risk-on"/"risk-off" phases so common post-crisis in response to central banks' words and actions gave way to a more differentiated pattern in sync with political statements and events. Hence, in particular, the more heterogeneous movements of financial prices across asset classes, sectors and regions in the wake of the US election and in light of evolving prospects for fiscal expansion, tax cuts, deregulation and protectionism. This shift went hand in hand with the opening-up of an unprecedented wedge between indices of policy uncertainty, which soared, and of financial market volatility, which sank.

That said, central banks continued to exert a significant influence on markets. Largely reflecting the monetary policy outlook and central bank asset purchases, an unusually wide gap opened up between the US dollar yield curve, on the one hand, and its yen and euro equivalents, on the other. This contributed to sizeable cross-currency portfolio flows, often on a currency-hedged basis, helping to explain a puzzling market anomaly: the breakdown of covered interest parity (Chapter II). The corresponding premium on dollar funding through the FX market relative to the money market also signalled a more constrained use of banks' balance sheet capacity. Banks were less willing than pre-crisis to engage in balance sheet-intensive arbitrage (Chapter V).

The condition and near-term prospects of the financial industry improved but remained challenging (Chapter V). The outlook for higher interest rates and a stronger economy helped bank equity prices to outperform the market. Profits in crisis-hit countries increased somewhat, supporting banks' efforts to further replenish their capital cushions. And profitability was generally higher in countries experiencing strong financial cycle expansions. Even so, market scepticism lingered, as reflected in comparatively low price-to-book ratios or credit ratings for many banks. Euro area banks were especially affected as they struggled with excess capacity and high non-performing loans in some member countries. Profitability in the insurance sector of the main advanced economies changed little, weighed down even more than that of the banking sector by persistently low interest rates.

Sustainability

This brief review of the past year indicates that the global economy's performance has improved considerably and that its near-term prospects appear the best in a long time. Moreover, the central scenario delineated by private and official sector forecasts points to further gradual improvement: headwinds abate, the global economy gathers steam, monetary policy is gradually normalised, and the expansion becomes entrenched and sustainable. Indeed, the financial market sentiment is broadly consistent with this scenario.

As always, however, such outcomes cannot be taken for granted. Market and official expectations have been repeatedly disappointed since the GFC. And there is generally not much of value in macroeconomic forecasts beyond the near term. By construction, they assume a return to long-term trends, which is one reason why they do not anticipate recessions. Moreover, while its pace has been moderate overall, the current expansion is already one of the longest on record.

Against this backdrop, it is worth examining key medium-term risks to the outlook. We next consider, sequentially, an inflation spurt, financial cycle risks, a failure of investment to take over the lead from potentially weaker consumption, and the protectionist threat that could hit trade and roll back globalisation.

Inflation

A rise in inflation, forcing central banks to tighten substantially, has been the typical trigger of postwar recessions. The latest one was an exception: while monetary policy did tighten somewhat, it was the collapse of a financial boom under its own weight that played the main role. Could the more typical postwar pattern reassert itself (Chapter IV)?

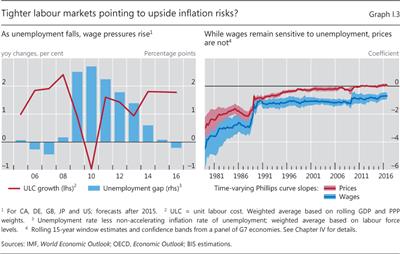

There are prima facie reasons to believe inflation could increase significantly (Graph I.3, left-hand panel). It has already been edging up. More importantly, economic slack is vanishing, as suggested by estimates of the relationship between output and its potential ("output gaps") and, even more so, by labour market indicators. And this is happening in several countries simultaneously - a development not to be underestimated given evidence that global measures of slack help predict inflation over and above domestic ones. These signs suggest that it would be unwise to take much comfort from the fact that higher inflation has recently mirrored mainly a higher oil price: they could point to greater inflation momentum going forward.

At the same time, a substantial and lasting flare-up of inflation does not seem likely (Chapter IV). The link between economic slack and price inflation has proved rather elusive for quite some time now (Graph I.3, right-hand panel). To be sure, the corresponding link between labour market slack and wage inflation appears to be more reliable. Even so, there is evidence that its strength has declined over time, consistent with the loss of labour's "pricing" power captured by labour market indicators (same panel). And, in turn, the link between increases in unit labour costs and price inflation has been surprisingly weak.

The deeper reasons for these developments are not well understood. One possibility is that they reflect central banks' greater inflation-fighting credibility. Another is that they mainly mirror more secular disinflationary pressures associated with globalisation and the entry of low-cost producers into the global trading system, not least China and former communist countries. Alongside technological pressures, these developments have arguably sapped both the bargaining power of labour and the pricing power of firms, making the wage-price spirals of the past less likely.

These arguments suggest that, while an inflation spurt cannot be excluded, it may not be the main factor threatening the expansion, at least in the near term. Judging from what is priced in financial assets, also financial market participants appear to hold this view.

Financial cycle risks

In light of the above, the potential role of financial cycle risks comes to the fore. The main cause of the next recession will perhaps resemble more closely that of the latest one - a financial cycle bust. In fact, the recessions in the early 1990s in a number of advanced economies, without approaching the depth and breadth of the latest one, had already begun to exhibit similar features: they had been preceded by outsize increases in credit and property prices, which collapsed once monetary policy started to tighten, leading to financial and banking strains. And for EMEs, financial crises linked to financial cycle busts have been quite prominent, often triggered or amplified by the loss of external funding; recall, for instance, the Asian crisis some 20 years ago.

Leading indicators of financial distress constructed along the above lines do point to potential risks (Chapter III). Admittedly, such risks are not apparent in the countries at the core of the GFC, where domestic financial booms collapsed, such as the United States, the United Kingdom or Spain. There, some private sector deleveraging has taken place and financial cycle expansions are still comparatively young. The main source of near-term concerns in crisis-hit economies is the failure to fully repair banks' balance sheets in some countries, notably in parts of the euro area, especially where the public sector's own balance sheet looks fragile (Chapter V). Political uncertainties compound these concerns.

Rather, the classical signs of financial cycle risks are apparent in several countries largely spared by the GFC, which saw financial expansions gather pace in its aftermath. This group comprises several EMEs, including the largest, as well as a number of advanced economies, notably some commodity exporters buoyed by the long post-crisis commodity boom. In all of these economies, of course, interest rates have been very low, or even negative, as inflation has stayed low, or even given way to deflation, despite strong economic performance. Financial cycles in this group are at different stages. In some cases, such as China, the booms are continuing and maturing; in others, such as Brazil, they have already turned to bust and recessions have occurred, although without ushering in a full-blown financial crisis.

EMEs face an additional challenge: the comparatively large amount of FX debt, mainly in US dollars (Chapters III, V and VI). Dollar debt has typically played a critical role in EME financial crises in the past, either as a trigger, such as when gross dollar-denominated capital flows reversed, or as an amplifier. The conjunction of a domestic currency depreciation and higher US dollar interest rates can be poisonous in the presence of large currency mismatches. From 2009 to end-2016, US dollar credit to non-banks located outside the United States - a bellwether BIS indicator of global liquidity - soared by around 50% to some $10.5 trillion; for those in EMEs alone, it more than doubled, to $3.6 trillion.

Compared with the past, several factors mitigate the risk linked to FX debt. Countries have adopted more flexible exchange rate regimes: while no panacea, these should make currency crashes less likely and induce less FX risk-taking ex ante. Countries have also built up foreign currency war chests, which should cushion the blow if strains emerge. And the amounts of FX debt in relation to GDP are, on balance, still not as high as before previous financial crises. Indeed, several countries have absorbed large exchange rate adjustments in recent years. Even so, vulnerabilities should not be taken lightly, at least where large amounts of FX debt coincide with outsize domestic financial booms. This is one reason why a tightening of US monetary policy and a US dollar appreciation may signal global financial market retrenchment and higher risk aversion, with the dollar acting as a kind of "fear gauge". 2

More generally, while leading indicators of financial distress provide a general sense of a build-up of risk, they have a number of limitations. In particular, they tell us little about the precise timing of its materialisation, the intensity of strains or their precise dynamics. After all, policymakers have taken major steps post-crisis to improve the strength of regulatory and supervisory frameworks, which could alter the statistical relationships found in the data. For instance, many EMEs have had recourse to a wide array of macroprudential measures to tame the financial cycle. While these have not succeeded in avoiding the build-up of outsize financial booms, they can make the financial system more resilient to the subsequent bust. As the experience of Brazil indicates, this may not prevent a recession, but it may limit the risk of a financial crisis. These limitations suggest that the indicators need to be treated with caution.

Consumption and investment

Short of any serious financial strains, the expansion could end because of weakness in domestic aggregate demand (Chapter III). In many countries, the recent expansion has been consumption-led, with consumption growth outpacing that of GDP. By contrast, investment has been comparatively subdued until recently. Could consumption weaken? And what are the prospects for a sustained strengthening of investment? Naturally, the expansion would be more sustainable if investment became the main growth engine. This would boost productivity and help keep medium-term inflationary pressures in check. Empirical evidence indicating that consumption-led growth is less sustainable is consistent with this view.

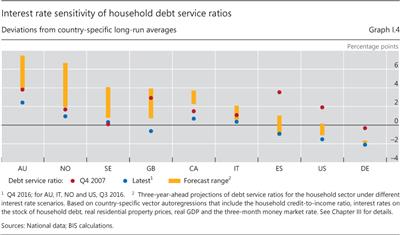

While consumption could weaken as a result of smaller employment gains as capacity constraints are hit, the more serious vulnerabilities reflect the continued accumulation of debt, sometimes on the back of historically high asset prices. Asset price declines could put pressure on balance sheets, especially if they coincided with higher interest rates. Indeed, BIS research has uncovered an important but underappreciated role of debt service burdens in driving expenditures (Chapter III).

An analysis of the debt service burden-induced interest rate sensitivity of consumption points to vulnerabilities (Chapter III and Graph I.4). These are apparent in economies that have experienced household credit booms post-crisis, often alongside strong property price increases, including several small open economies and some EMEs. Increases in interest rates beyond what is currently priced in markets could weaken consumption considerably. By contrast, in some crisis-hit countries, such as the United States, the safety cushion is considerably larger following the deleveraging that has already taken place.

Investment has been rather weak post-crisis in relation to GDP, at least in advanced economies (Chapter III). The drop has reflected in part a correction in residential investment after the pre-crisis boom, but also a decline in the non-residential component. In EMEs, investment has proved generally more resilient, notably reflecting the surge in China and the associated boost to commodity prices. Post-crisis investment weakness, coupled with resource misallocations, has no doubt contributed to the further deceleration of productivity growth. Could the recent welcome pickup in investment fail to strengthen enough?

While interest rates matter for investment, a bigger role is played by profits, uncertainty and cash flows. From this perspective, while the very high readings of policy uncertainty indicators may be a reason for concern, they have not sapped the recent pickup so far. In EMEs, a cause for concern has been the sharp increase in corporate debt in several economies, sometimes in foreign currency. Indeed, empirical evidence points to a link between US dollar appreciation and investment weakness in many EMEs (Chapter III). China stands out, given the combination of unprecedented debt-financed investment rates and signs of excess capacity and unprofitable businesses. A sharp slowdown there could cause much broader ripples in EMEs, including through a slump in commodity prices.

Deglobalisation

Since the GFC, protectionist arguments have been gaining ground. They have been part of a broader social and political backlash against globalisation. Rolling back globalisation would strike a major blow against the prospects for a sustained and robust expansion. Investment would be the first casualty, given its tight link with trade. But the seismic change in institutional frameworks and policy regimes would have a broader and longer-lasting impact. It is worth exploring these issues in more detail, which is why we devote a whole chapter to them in this year's Report (Chapter VI).

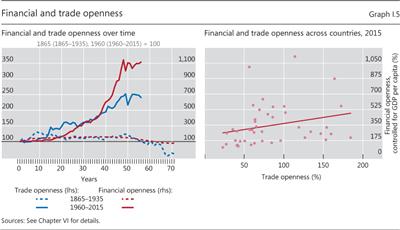

As is well known, the gradual process of tighter integration that the global economy has witnessed since World War II - and which took a quantum leap following the end of the cold war era - is not unprecedented (Graph I.5, left-hand panel). A first globalisation wave took place starting in the second half of the 19th century, became entrenched during the gold standard period, and took a big blow with World War I before collapsing a decade later in the wake of the Great Depression.

There are similarities but also important differences between the two waves. Both periods saw a major rise in real and financial integration, driven by political decisions and supported by technological innovation. But, economically, the more recent wave has been both broader and deeper, even as it has relied less on migration flows. Hence the unprecedented growth in global value chains (GVCs) and cross-border financial claims.

While there is a natural tendency to discuss real and financial globalisation separately, the two are intertwined. Exports and imports rely heavily on international financing. Transnational ownership of companies through foreign direct investment (FDI) boosts trade, spreads organisational and technological know-how, and gives rise to global players. Banks and other service providers tend to follow their customers across the world. Financial services are themselves an increasing portion of economic activity and trade. And the relevance of national borders is further blurred by the overwhelming use of a handful of international currencies, mostly the US dollar, as settlement medium and unit of account for trade and financial contracts.

A look at the data confirms the close relationship between real and financial globalisation. Across countries, the pattern of financial linkages mirrors rather well that of trade (Chapter VI and Graph I.5, right-hand panel). Historically, there have been periods, such as the Bretton Woods era, in which policymakers sought greater trade integration while at the same time deliberately limiting financial integration, so as to retain more policy autonomy. But, over time, the regimes proved unsustainable, and financial integration grew apace.

That said, the financial side has also developed a life of its own. Across countries, this reflects in particular the benefits of agglomeration, which cause financial activity to concentrate in financial centres, and tax arbitrage, which encourages companies to locate headquarters in specific countries. Since the early 1990s financial linkages have far outstripped trade, in contrast to what available data suggest about the first globalisation wave.

There is some evidence that globalisation has slowed post-crisis, but it is not in retreat. Trade in relation to world GDP and GVCs have plateaued. And while financial integration broadly defined seems to have moderated, bank lending has pulled back. However, a closer look at the BIS statistics indicates that the contraction largely reflects a pullback by euro area banks and is regional in nature. Banks from Asia and elsewhere have taken over, and integration has not flagged. Moreover, securities issuance has outpaced bank lending, in line with the rise of institutional investors and asset managers.

From a policy perspective, the reasons for the slowdown matter. The slowdown would be less of an issue if it simply reflected cyclical factors and unconstrained economic decisions. Much of the decline in trade and financial linkages seems to have that character. It would be more of a concern if it reflected national biases. In both trade and finance, there are signs that this too may have started to occur. Hence the increase in trade restrictions and in ring-fencing in the financial sector. No doubt some of those decisions may be justified, but they could herald a broader and more damaging backlash.

Formal statistical evidence, casual observation and plain logic indicate that globalisation has been a major force supporting world growth and higher living standards. Globalisation has helped lift large parts of the world population out of poverty and reduce inequality between countries. It is simply unimaginable that EMEs could have grown so much without being integrated in the global economy. Conceptually, integration spreads knowledge, fosters specialisation and allows production to take place where costs are lower. It is akin to what economists would call a series of major positive supply side shocks that, in turn, promote demand.

At the same time, it is also well known that globalisation poses challenges. First, its benefits may be unevenly distributed, especially if economies are not ready or able to adapt. Trade displaces workers and capital in those sectors that are more exposed to international competition. And it may also increase income inequality in some countries. Opening up trade with countries where labour is abundant and cheap puts pressure on wages in those where it is scarcer and more expensive. It can thus erode labour's pricing power, tilt the income distribution towards capital, and widen the skilled/unskilled labour wedge. Second, opening up the capital account without sufficient safeguards can expose the country to greater financial risks.

The empirical evidence confirms, but also qualifies, the impact on labour markets and income distribution (Chapter VI). Low-skill jobs have migrated to low-cost producers as large industrial segments have been displaced in the less competitive economies. And while studies have found an impact on income inequality, they have generally concluded that technology has been much more important: the mechanisms are similar and naturally interact, but the spread of technology across the whole economy has made its influence more pervasive.

It is also well recognised by now that greater financial openness can channel financial instability. Just as with domestic financial liberalisation, unless sufficient safeguards are in place, it can increase the amplitude of financial booms and busts - the so-called "procyclicality" of the financial system. In the 85th Annual Report, we devoted a whole chapter to this issue, exploring weaknesses in the international monetary and financial system. 3 The free flow of financial capital across borders and currencies can encourage exchange rate overshooting, exacerbate the build-up of risks and magnify financial distress - that is, increase the system's "excess elasticity". The dominant role of the US dollar as international currency adds to this weakness, by amplifying the divergence between the interests of the country of issue and the rest of the world. 4 Hence the outsize influence of US monetary policy on monetary and financial conditions globally.

These side effects of globalisation do not imply that it should be rolled back; rather, they indicate that it should be properly governed and managed (see below). A roll-back would have harmful short-term and long-term consequences. In the short term, greater protectionism would weaken global demand and jeopardise the durability and strength of the expansion, by damaging trade and raising the spectre of a sudden stop in both investment and FDI. In the longer term, it would endanger the productivity gains induced by greater openness and threaten a revival of inflation. In more closed, possibly financially repressed economies, the temptation would be to inflate debts away, and wage-price spirals could again become more likely, raising the risk of a return of the stagflation of yesteryear.

Policy

Given the risks ahead, how can policymakers best turn the current upswing into sustainable and robust global growth? Over the past year, a broad consensus has been emerging about the need to rebalance the policy mix, lightening the burden on monetary policy and relying more on fiscal measures and structural reforms. Still, views differ about policy priorities. If we are to understand how to adjudicate among them, we need to take a step back and consider some broader questions underlying current analytical frameworks.

Much of the current policy discourse revolves around two propositions. The first is that policymakers are able to fine-tune the economy, by operating levers that influence aggregate demand, output and inflation in a powerful and predictable way. The second is that there is a neat distinction between the short run, the preserve of aggregate demand, and the long run, the preserve of aggregate supply.

While there is clearly some truth in both propositions, reality is much more nuanced. As history has repeatedly indicated, it is all too easy to overestimate policymakers' ability to steer the economy. Moreover, aggregate demand and supply interact so that the short and long run blend into each other.

The post-crisis experience is a sobering illustration of these nuances. It has proved much harder than expected to boost growth and inflation despite unprecedented measures. And the recession, itself the legacy of the previous unsustainable financial boom, appears to have left profound scars: output losses have been huge and productivity growth persistently weakened.

This experience highlights the need to evaluate policy in a long-term context. Policy actions taken at a given point in time, regardless of whether they target demand or supply, have long-lasting influences. And by affecting, for instance, the cumulative stock of debt or the room for policy manoeuvre, they help shape the economic environment that policymakers take as given, or "exogenous", when the future becomes today. 5 Unless these effects are properly taken into account, policy options can narrow substantially over time, as appears to have happened over the past decade.

This perspective suggests that, rather than seeking to fine-tune the economy, a more promising approach would be to take advantage of the current strong tailwinds to strengthen the economy's resilience, at both the domestic and global level. The notion of resilience helps avoid the trap of overestimating policymakers' economic steering powers. And it fosters the longer-term horizons so essential to place policy in its proper intertemporal context.

Resilience, broadly defined, means more than just the capacity to withstand unforeseen developments or "shocks". It also means reducing the likelihood that shocks will materialise in the first place, by limiting policy uncertainty and the build-up of vulnerabilities, such as those stemming from financial imbalances. 6 And it means increasing the economy's adaptability to long-term trends, such as those linked to ageing populations, slowing productivity, technology or globalisation. We next discuss how strengthening resilience can help address the current domestic and global challenges.

Building resilience: the domestic challenge

Building resilience domestically is a multifaceted challenge. Consider, in turn, monetary, fiscal and structural policies as well as their role in tackling the financial cycle.

There is a broad consensus now that monetary policy has been overburdened for far too long. It has become, in that popular phrase, "the only game in town". In the process, central bank balance sheets have become bloated, policy interest rates have been ultra-low for a long time, and central banks have extended their direct influence way out along the sovereign yield curve as well as to other asset classes, such as private sector debt and even equity.

Building resilience would suggest attaching particular importance to enhancing policy space, so as to be better prepared to tackle the next recession. This, in turn, would suggest taking advantage of the economy's tailwinds to pursue normalisation with a steady hand as domestic circumstances permit. "As domestic circumstances permit" is an essential qualifier, since how far normalisation is possible depends on country-specific factors, involving both the economy and monetary frameworks. The scope differs substantially across countries. Even so, the broad strategy could be common.

Normalisation presents a number of tough challenges (Chapter IV). Many of them stem from the journey's starting point - the unprecedented monetary conditions that have prevailed post-crisis. As markets have grown used to central banks' helping crutch, debt levels have continued to rise globally and the valuation of a broad range of assets looks rich and predicated on the continuation of very low interest rates and bond yields (Chapter II). On the one hand, heightened uncertainty naturally induces central banks to move very gradually with interest rates, and even more so with their balance sheets, with changes that are well telegraphed. On the other hand, that very gradualism implies a slower build-up of policy space. And it may also induce further risk-taking and promote the conditions that make a smooth exit harder. The risk of a snapback in bond yields, for instance, looms large. 7 Trade-offs are further complicated by the spillovers that domestic actions may have globally, especially in the case of the US dollar.

As a result, the road is bound to be bumpy. Normalisation may well not proceed linearly, but in fits and starts, as central banks test the waters in light of evolving conditions. And yet it is essential for financial markets and the broader economy to shake off their unusual dependence on central banks' unprecedented policies.

Building resilience through fiscal policy has two dimensions. The first is to prioritise the use of any available fiscal space. Several areas spring to mind. One is to support growth-friendly structural reforms (see below). Another is to reinforce support for globalisation by addressing the dislocations it can cause. Here, more general approaches appear superior to targeted ones, since the specific firms and individuals affected may be hard to identify. The basic principle is to save people, not jobs, by promoting retraining and the flexible reallocation of resources. Last but not least, public support for balance sheet repair remains a priority where private sources have been exhausted. Resolving non-performing loans is paramount for unlocking the financing of productive investments (Chapter V). What would be unwise at the current juncture would be simply to resort to deficit spending where the economy is close to full employment. This does not rule out the streamlining of tax systems or judicious and well executed public investments. But, as always, implementation is of the essence and far from straightforward, as the historical record suggests.

The second dimension concerns enhancing fiscal space over time. A precondition is its prudent measurement. As discussed extensively in last year's Annual Report, this requires incorporating in current methodologies a number of factors that tend to be underplayed or excluded - the need for a buffer for potential financial risks, realistic financial market responses to higher sovereign risks, and the burden of ageing populations. It also requires considering the impact that the combination of snapback risk and central bank large-scale asset purchases might have on the interest sensitivity of government deficits (Chapter IV). More generally, a prudent assessment of fiscal space could anchor the needed medium-term consolidation of public finances.

Building resilience through structural policies is essential. Structural policies are the only ones that hold the promise of raising the long-term growth potential and fostering an environment conducive to long-term investment. Unfortunately, far from speeding up, implementation has been slowing down. This has occurred even though the empirical evidence indicates that, contrary to a widespread belief, many measures do not depress aggregate demand even in the short run. 8 Ostensibly, the political costs of reform exceed the economic ones. Here, just as with the globalisation-induced challenges, it is the concentration of the costs on specific groups that matters most.

The needed structural reforms are largely country-specific. Their common denominator is fostering entrepreneurship and the rapid take-up of innovation, limiting rent-seeking behaviour. In addition, an underappreciated aspect - one which only now has begun to receive attention - is to ensure the flexible reallocation of resources, given the debilitating impact rigidities can have on the economy's shock-absorbing capacity and on productivity growth. Steps in that direction would also go a considerable way towards addressing the dislocations from globalisation. Especially worrisome is the high percentage of firms unable to cover interest costs with profits - "zombie firms" - despite historically low interest rates (Chapter III). This points to considerable obstacles in redeploying resources to their more productive uses.

From a medium-term perspective, it would be important that monetary, fiscal and even structural measures be part of a shift towards policy frameworks designed to address a critical source of vulnerabilities - the financial cycle. Indeed, the inability to come to grips with the financial cycle has been a key reason for the unsatisfactory performance of the global economy and limited room for policy manoeuvre. 9 And, as discussed in detail in previous Annual Reports, it would be unwise to rely exclusively on prudential policy, let alone on macroprudential measures, to tame it. 10 The recent experience of EMEs, where these measures have been deployed aggressively, confirms that they cannot by themselves prevent the build-up of imbalances.

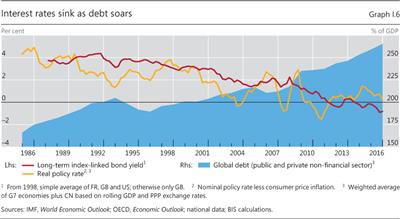

Tackling the financial cycle would call for more symmetrical policies. Otherwise, over long horizons, failing to constrain financial booms but easing aggressively and persistently during busts could lead to successive episodes of serious financial stress, a progressive loss of policy ammunition and a debt trap. Along this path, for instance, interest rates would decline and debt continue to increase, eventually making it hard to raise interest rates without damaging the economy (Graph I.6). From this perspective, there are some uncomfortable signs: monetary policy has been hitting its limits; fiscal positions in a number of economies look unsustainable, especially if one considers the burden of ageing populations; and global debt-to-GDP ratios have kept rising.

Building resilience: the global challenge

While there is a lot that domestic policy can do to build resilience, certain challenges call for a global response. The goal is to set out a clear and consistent multilateral framework - the rules of the game - for actions to be taken either at the national level or jointly internationally. Those rules would naturally vary in terms of specificity and tightness depending on the area, ranging from broad principles to common standards. Consider, in turn, five key areas: prudential standards, crisis management mechanisms, trade, taxation and monetary policy.

A first priority is to finalise the financial (prudential) reforms under way (Chapters V and VI). A core of common minimum standards in the financial sphere is a precondition for global resilience in an integrated financial world. Such standards avoid a perilous race to the bottom. The reforms under way are not perfect, but this is no time to weaken safeguards or add another source of uncertainty that would hinder the necessary adjustments in the financial industry (Chapter V).

Among the reforms, completing the agreement on minimum capital and liquidity standards - Basel III - is especially important, given the role banks play in the financial system. The task is to achieve agreement without, in the process, diluting the standards in the false belief that this can support growth. There is ample empirical evidence indicating that stronger institutions can lend more and are better able to support the economy in difficult times. 11 A sound international agreement, supported by additional measures at the national level, combined with the deployment of effective macroprudential frameworks, would also reduce the incentive to roll back financial integration.

A second priority is to ensure that adequate crisis management mechanisms are in place. After all, regardless of the strength of preventive measures, international financial stress cannot be ruled out. A critical element is the ability to provide liquidity to contain the propagation of strains. And that liquidity can only be denominated in an international currency, first and foremost the US dollar, given its dominant global role (Chapters V and VI). At a minimum, this means retaining the option of activating, when circumstances require, the inter-central bank swap arrangements implemented post-crisis.

A third priority is to ensure that open trade does not become a casualty of protectionism. A key to postwar economic success has been increased trade openness built around the multilateral institutions that support it. Here again, the arrangements are by no means perfect. It is well known, for instance, that the World Trade Organization's global trading rounds have ground to a halt and that its dispute settlement mechanism is overburdened. Even so, it would be a mistake to abandon multilateralism: the risk of tit-for-tat actions is simply too great. While open trade creates serious challenges, rolling it back would be just as foolhardy as rolling back technological innovation.

A fourth, complementary, priority is to seek a more level playing field in taxation. Tax arbitrage across jurisdictions is one factor that has fuelled resentment of globalisation and has no doubt contributed to income and wealth inequality within countries, including by encouraging a race to the bottom in corporate taxation. Several initiatives have been under way under the aegis of the G20. But efforts in this area could be stepped up.

Beyond these priorities, it is worth exploring further the room for greater monetary policy cooperation - the fifth area. As discussed in detail in previous Annual Reports, its desirability is due to the conjunction of large spillovers from international-currency jurisdictions with the limited insulation properties of exchange rates. Cooperation would help limit the disruptive build-up and unwinding of financial imbalances. In increasing degree of ambition, options include enlightened self-interest, joint decisions to prevent the build-up of vulnerabilities, and the design of new rules of the game to instil more discipline in national policies. While the conditions for tighter forms of cooperation are not fulfilled at present, deepening the dialogue to reach a better agreement on diagnosis and remedies is a precondition for further progress.

These courses of action share a thread. They recognise that, just like technology, globalisation is an invaluable common resource that offers tremendous opportunities. The challenge is to make sure that it is perceived as such rather than as an obstacle, and that those opportunities are turned into reality. It is dangerous for governments to make globalisation a scapegoat for the shortcomings of their own policies. But it is equally dangerous not to recognise the adjustment costs that globalisation entails. Moreover, managing globalisation cannot be done just at national level; it requires robust multilateral governance. For lasting global prosperity, there is no alternative to the sometimes tiring and frustrating give-and-take of close international cooperation.

Endnotes

1 See Chapter I of the 86th Annual Report.

2 For a discussion of this fear gauge as an alternative to the popular VIX, see H S Shin, "The bank/capital markets nexus goes global", speech at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 15 November 2016.

3 See Chapter V of the 85th Annual Report.

4 For an elaboration on the role of the US dollar in the system, see C Borio, "More pluralism, more stability?", presentation at the Seventh High-level Swiss National Bank-International Monetary Fund Conference on the International Monetary System, Zurich, 10 May 2016.

5 See Chapter I of the 86th Annual Report.

6 See "Economic resilience: a financial perspective", BIS note submitted to the G20 on 7 November 2016.

7 For a description and documentation of one of the mechanisms involved, see D Domanski, H S Shin and V Sushko, "The hunt for duration: not waving but drowning?", BIS Working Papers, no 519, October 2015.

8 For a detailed analysis of this question, see R Bouis, O Causa, L Demmou, R Duval and A Zdzienicka, "The short-term effects of structural reforms: an empirical analysis", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no 949, March 2012.

9 See C Borio, "Secular stagnation or financial cycle drag?", keynote speech at the National Association for Business Economics, 33rd Economic Policy Conference, Washington DC, 5-7 March 2017. The issue is also discussed in Chapter I of the 84th, 85th and 86th Annual Reports.

10 For an elaboration on such a macro-financial stability framework, see Chapter I of the 84th and 85th Annual Reports.