Estimating the time-varying price elasticity of housing supply

Box extracted from chapter "Monetary policy and housing markets: insights using a novel measure of housing supply elasticity"

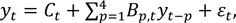

We construct estimates of the supply elasticity using a time-varying parameter Bayesian vector-autoregression (BVAR) model, similar to Gorea et al (forthcoming). For each country in our sample, we estimate the following regression:

For each country in our sample, we estimate the following regression:

where the dependent variable, yt, is a three-by-one vector of variables that includes the quarter-on-quarter growth rates for house prices, building permits and GDP. We use a four quarter lag structure of the BVAR model to capture dynamics in the three endogenous variables. Ct is a vector of time-varying country-specific intercepts, Bv,t is a matrix of time-varying coefficients, and εt is an error term that is normally distributed with a zero mean and a time-varying covariance matrix.

and GDP. We use a four quarter lag structure of the BVAR model to capture dynamics in the three endogenous variables. Ct is a vector of time-varying country-specific intercepts, Bv,t is a matrix of time-varying coefficients, and εt is an error term that is normally distributed with a zero mean and a time-varying covariance matrix.

Our estimation sample includes 21 countries (see Graph 2.C for the specific countries in our study). The length of the time series varies across countries. For most advanced economies, the data start in the 1970s or the 1980s, while for emerging market economies, the sample starts in the 1990s and 2000s.

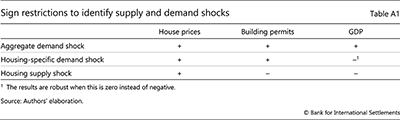

We identify shocks through sign restrictions, adapting the identification restrictions imposed in Baumeister and Peersman (2013) to the context of the housing market. Table A1 summarises the sign restrictions imposed on the impact (within-quarter) responses to shocks of the three endogenous variables used in the model.

The identified demand shocks are crucial for our estimates of the price elasticity of housing supply because they enable us to trace out movements along the supply curve. For our main analysis we use aggregate demand shocks, defined as shocks which push house prices, building permits and aggregate demand in the same direction. The sign restrictions additionally identify housing-specific demand shocks which push prices and quantities up, but GDP down. These shocks are assumed to reduce current GDP, as they tend to disproportionately reallocate investment away from other productive sectors of the economy towards residential construction. We distinguish between the two types of demand shocks (aggregate and housing-specific) to better capture the effects of monetary policy that would propagate through the economy in the same way as aggregate demand shocks. We further identify housing supply shocks using our model. These are shocks that move house prices in the opposite direction to building permits and GDP.

We distinguish between the two types of demand shocks (aggregate and housing-specific) to better capture the effects of monetary policy that would propagate through the economy in the same way as aggregate demand shocks. We further identify housing supply shocks using our model. These are shocks that move house prices in the opposite direction to building permits and GDP.

We use the impulse responses from aggregate demand shocks to compute estimates of the price elasticity of housing supply. As our model features time-varying parameters, we simulate the impulse responses for building permits and house prices to aggregate demand shocks for each country and quarter. We then use the impulse responses at horizon zero to compute the short-run price elasticity of housing supply, defined as the percentage change in building permits divided by the percentage change in house prices. This elasticity serves as our baseline measure of how much new housing supply changes following a change in house prices.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS. We use building permits to proxy for the quantity of new housing supply because data on permits are available for a longer time period than data on new housing starts or completions for most countries in our sample. For countries where we have reliable data on starts and permits, we find that the two series are especially highly correlated at lag zero or one, suggesting that permits are a reliable predictor of starts and new supply.

We use building permits to proxy for the quantity of new housing supply because data on permits are available for a longer time period than data on new housing starts or completions for most countries in our sample. For countries where we have reliable data on starts and permits, we find that the two series are especially highly correlated at lag zero or one, suggesting that permits are a reliable predictor of starts and new supply.  Estimates of the price elasticity of housing supply derived from housing-specific demand shocks are similar in terms of dynamics to those derived from aggregate demand shocks. In addition, our results are robust to assuming a zero impact on GDP for the housing-specific demand shock.

Estimates of the price elasticity of housing supply derived from housing-specific demand shocks are similar in terms of dynamics to those derived from aggregate demand shocks. In addition, our results are robust to assuming a zero impact on GDP for the housing-specific demand shock.  Using the supply elasticities based on housing-specific demand shocks does not materially change our results on the effects of monetary policy on house prices and rents.

Using the supply elasticities based on housing-specific demand shocks does not materially change our results on the effects of monetary policy on house prices and rents.