Two defaults at CCPs, 10 years apart

Central counterparties have been described as "unlikely heroes" for their handling of the Lehman Brothers' default (Norman (2011)). CCPs proved resilient during the crisis, continuing to clear contracts even when bilateral markets dried up (Domanski et al (2015)). Lehman had derivative portfolios at a number of CCPs across the world and, with one exception, these were auctioned, liquidated or transferred within weeks of the default without exhausting the collateral Lehman had provided (Cunliffe (2018), Monnet (2010)). One example is the unwinding of Lehman's interest rate swaps portfolio cleared in London (66,390 trades, $9 trillion notional), which used up about a third of the margin held, so that neither the CCP nor its members sustained any losses.

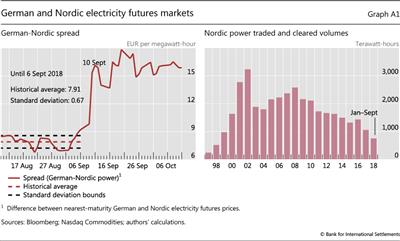

Yet 10 years later, a single trader with a much smaller portfolio presented a CCP with a much greater challenge. That tribulation came on 10 September 2018, when Einar Aas, a Norwegian trader, failed to pay a margin call to the commodities arm of Nasdaq Clearing AB in Sweden. Aas had bet that Nordic and German electricity prices would converge, by trading in futures on the Norwegian commodity derivatives exchange, Nasdaq Oslo ASA, which clears all trades with the Swedish CCP. Weather forecasts and a change in German carbon emission policies pushed the two prices apart, driving the value of Aas's position down sharply (Graph A1, left-hand panel). Correlation strategies of this kind were once described, in the case of Long-Term Capital Management, as "picking up nickels in front of a steamroller" (Lowenstein (2000)). When Nasdaq made a margin call that Aas failed to pay in full, he was put into default the next morning.

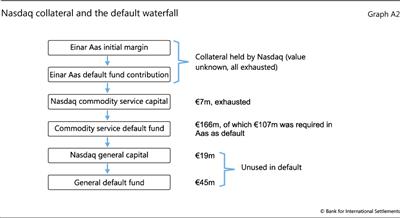

The CCP sought to manage the default by selling the position. In the following days, an auction was held for Aas's portfolio with four of Nasdaq's other members. The winning bid resulted in a loss of €114 million in excess of the collateral Aas had provided. For commodities, Nasdaq's "default waterfall" (once Aas's collateral was exhausted) started with capital of €7 million, after which it tapped a €166 million fund made up of contributions from the non-defaulting members (Nasdaq has three services, each with a separate default fund). In the event, this sufficed to absorb the loss resulting from Aas's default. In addition to the funds consumed, another layer of capital was available, as well as a general default fund covering all Nasdaq Clearing's services (Graph A2).

For a CCP to exhaust a defaulter's collateral is unusual, even in the case of a large default such as Lehman's. CPMI-IOSCO (2017b) contains guidance on how CCPs should set their margin to prevent this from happening. The guidance includes calculating initial margins using a sufficiently long time horizon, using assumptions on how liquid the market is, and allowing only for prudent offsets between products. Although there is currently no public record of how much collateral Aas provided, Nasdaq has publicly disclosed how it calculated his initial margins. For his Nordic and German futures positions, Nasdaq required Aas to pay 99.2% of the biggest two-day market movements over the previous year, plus 25% of the biggest two-day movement that year. But the CCP also gave him a correlation offset of 50% on the margin, assuming that German and Nordic electricity prices would continue to move in parallel. Moreover, Aas was not required to pay any additional margin, even though the position made up a large proportion of the Nordic power market - a market that had been shrinking significantly in volume over the past decade (Graph A1, right-hand panel). This was despite the fact that liquidation costs are generally high for portfolios which are large relative to the available market. The reasons for this are unclear, but some observers have suggested that margin-setting may sometimes reflect competitive pressures (Domanski et al (2015)).

How then was Lehman's default handled without losses in hard times, while Aas's default forced a CCP to pass losses to members? Lehman's portfolio, while large and complex, was relatively balanced and part of an even larger market. Although it was in supposedly more complex over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, CCPs had adequate strategies and collateral in place. This was in stark contrast to Aas's portfolio, which was undiversified and heavily concentrated in a smaller and less liquid market. These episodes underscore the importance of maintaining sufficient market liquidity for central clearing to support default management in stressed conditions, and of applying a reliable long-term perspective in order to set accurate margins (Cunliffe (2018)). So, although Lehman's portfolio was much larger, CCP default management teams could hedge and reduce risks, allowing orderly auctions to take place over a number of weeks following the default.

These two defaults happened 10 years apart, under very different circumstances. Yet the lesson is timeless: sound risk management and preparation make all the difference between a CCP that absorbs a shock, and one that propagates it.