Accounting for the increase in the stock of debt: credit demand vs credit supply

(Extract from page 44 of BIS Quarterly Review, December 2017)

Rising household debt can reflect either stronger credit demand or an increased supply of credit from lenders, or some combination of the two.

Unconstrained households can borrow in order to smooth consumption before an anticipated increase in income or after an unexpected temporary drop in income (eg illness, accidents, short-term unemployment). In addition, households borrow to finance investment in illiquid assets with high long-term returns such as housing (Kaplan et al (2014)). Credit demand might rise because households are optimistic about income prospects, or because costs (interest rates) are low. The post-Great Financial Crisis period has seen extraordinary monetary accommodation, very low borrowing rates and low returns on safe assets. This combination has lifted debt-financed demand for housing, either for own use or as an investment (eg in Germany, property has recently been referred to as "concrete gold").

Structural factors such as demographic shifts could also be playing a supporting role. Population growth could have contributed to the rise in credit in Australia and Canada. Structural factors combine with demand factors in Korea: returns on real estate investments have been especially high, encouraging households close to retirement to borrow to invest in buy-to-let properties with the aim of generating income for old age.

Favourable supply conditions can also boost credit to households. In Australia, for instance, heightened competition among lenders seems to have resulted in a relaxation of lending standards. There is some evidence that this may also matter for UK consumer credit (Bank of England (2017)). In Korea, solvency (loan-to-value ratios) and affordability (debt-to-income ratios) requirements on new loans have been relaxed as part of a broader easing of real estate regulation. In the United States, the government has supported the secondary mortgage market through its long-standing implicit guarantee of debt issued by government-sponsored enterprises. In addition, the post-crisis world has been marked by greater emphasis on a more traditional, retail-oriented approach to banking.

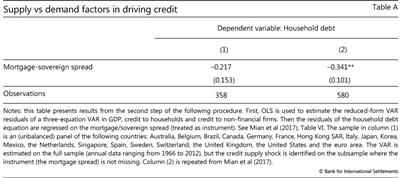

Table A presents evidence that supply factors may have been more important than demand in driving household credit in some jurisdictions. The coefficients are computed following Mian et al (2017), who estimate a proxy vector autoregression (VAR) in two steps. A negative (positive) coefficient implies that increases in credit to households that are not explained by the dynamics of GDP growth, credit to households itself and credit to non-financial firms are associated with narrow (wide) mortgage spreads, which are in turn more likely to be correlated with outward shifts in credit supply than in credit demand. The results shown in column 1 use the sample of countries listed in Table 1. These results are qualitatively consistent with the findings of Mian et al (2017), who consider a broader range of countries (column 2), although the estimates are not as precise because of the smaller sample size.

Between 2012 and 2016, the number of households in the 60+ age group owning buy-to-let properties has grown by about 50%, and accounts for most of the growth in such investments. The investments are largely debt-financed.

Between 2012 and 2016, the number of households in the 60+ age group owning buy-to-let properties has grown by about 50%, and accounts for most of the growth in such investments. The investments are largely debt-financed.