The ECB's QE and euro cross-border bank lending

There is growing evidence that the currency distribution of cross-border credit affects international monetary policy spillovers. While the existing literature has concentrated primarily on the US dollar, this article focuses on the euro. We find that the ECB's quantitative easing of January 2015 had a larger positive impact on cross-border bank credit in lender-borrower pairs with a higher share of euro-denominated bank claims. The effect was especially pronounced for lending to advanced economies outside the euro area. By contrast, the estimated effects on cross-border lending to EME borrowers were insignificant.1

JEL classification: F34, G15, G21.

The question of international monetary policy spillovers has gained prominence in the light of the exceptionally accommodative post-crisis monetary policy stance of advanced economy central banks. There is growing evidence that the currency distribution of cross-border credit plays a crucial role in determining the size, distribution and direction of such spillovers. McCauley et al (2015) have demonstrated that since the Great Financial Crisis, the outstanding US dollar credit to non-bank borrowers outside the United States has increased from $6 trillion to $9 trillion. Bruno and Shin (2015a) have documented that episodes of US dollar appreciation are associated with deleveraging by global banks and a tightening of global financial conditions. More recently, Avdjiev and Takáts (2016) have found that a higher bilateral US dollar share on the eve of the 2013 "taper tantrum" was associated with a lower growth rate of cross-border bank lending in its aftermath.

Virtually all existing studies examining the impact of the currency composition of international lending flows on cross-border monetary policy spillovers have concentrated on the US dollar. In this article, we shift the focus to the euro cross-border bank lending network, the second largest network after the US dollar network. More concretely, we take advantage of the recent enhancements to the BIS international banking statistics (IBS) to ask to what extent the share of euro-denominated cross-border bank claims explains the cross-sectional variation of the impact of the ECB's January 2015 quantitative easing (QE) programme on cross-border bank lending.

Our results indicate that a higher euro share in cross-border claims on the eve of the 2015 ECB QE announcement was associated with stronger growth in cross-border bank lending during this quarter. This result appears to be driven primarily by lending to advanced economies outside the euro area. By contrast, the estimated effects on cross-border lending to borrowers in emerging market economies (EMEs) tend to be insignificant.

Our findings contribute in two ways to the literature on the role of cross-border bank currency networks in the international transmission of monetary policy shocks. First, our results imply that the US dollar network is not unique and that the euro cross-border bank lending network responds to monetary policy shocks in a similar manner. This finding accords with emerging evidence that the euro is starting to take on some of the characteristics of the US dollar as a global funding currency (Shin (2015)). Second, our results suggest that currency networks respond to monetary policy shocks symmetrically. That is, the response to an easing shock (such as the one studied in this article) appears to be qualitatively similar to the response to a tightening shock (such as the 2013 Fed taper tantrum examined in Avdjiev and Takáts (2016)).

The rest of the feature is organised as follows. The next section introduces the BIS cross-border bank lending data used in our empirical analysis. The third section documents how widely the euro is used and how cross-border bank lending evolved before and after the January 2015 ECB QE announcement. The fourth section analyses the ECB QE econometrically to show how cross-border lending responded to euro loan exposure. The fifth section concludes.

Cross-border bank lending data

Our empirical analysis takes advantage of the Stage 1 Enhancements to the BIS international banking statistics (IBS). With these enhancements, the IBS now reflect the three key dimensions of international banking activity needed for our empirical exercise - (A) the borrower's residence, (B) the lending bank's nationality and (C) the currency composition of cross-border claims (Avdjiev et al (2015a)).2

The three dimensions yield a fairly comprehensive view of cross-border banking activity. Dimension (A), the residence of the borrower, helps to identify the country-specific borrowing drivers of cross-border bank lending dynamics. In particular, it lets us identify and control for factors related to credit demand in the borrowing country.

Dimension (B), the lender's nationality, ie the home of the highest-level banking entity in the corporate chain, respects the contours of banks' consolidated balance sheets rather than national borders. The international finance literature has traditionally focused on the residence of financial intermediaries as a key determinant of their behaviour. But Fender and McGuire (2010) and Cecchetti et al (2010) have argued that the lending bank's nationality tends to be much more relevant than its residence for the purposes of identifying the decision-making unit on the credit supply side. Nationality should better capture the factors that influence a bank's lending decisions, such as the performance or equity constraints of the bank as a whole.

The bank's nationality rather than its residence is especially useful if the loan is booked in an international financial centre. To see this, consider a German bank that lends to a borrower in Malaysia via its Hong Kong branch. Our proxy establishes a link between the German banking system (as the lender) and Malaysia (as the borrowing country). The alternative, ie looking at the bank's residence, would identify two cross-border bank lending links: one from Germany to Hong Kong SAR and another between Hong Kong and Malaysia. This would lead to two problems. First, one would consider Hong Kong as the borrowing economy in the former loan (Germany-Hong Kong), even though the loan is only intermediated through Hong Kong. Second, one would treat the Hong Kong banking system as the lender in the latter loan (Hong Kong-Malaysia), even though the Hong Kong-based banking unit is not the original supplier of credit.

Finally, we need the third dimension, currency denomination (C), for two reasons. First, the currency composition is used to investigate the impact of exposure to euro-denominated lending. Second, and more subtly, we also need to control for the impact of currency fluctuations on changes in the outstanding stocks of cross-border bank claims. Since cross-border bank claims are expressed in US dollars, currency movements lead to fluctuations in the dollar value of the claims. Adjusting for currency movements is particularly relevant when investigating the impact of monetary policy, because of its close relationship with the exchange rate.

The euro cross-border bank lending network

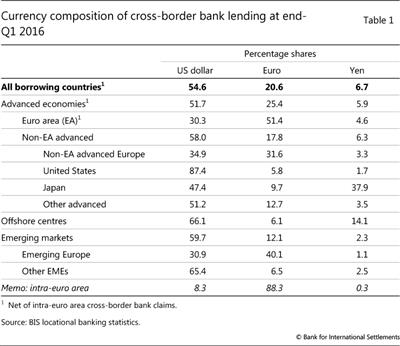

The euro is the second most used currency for cross-border bank lending. As of end-Q1 2016, euro-denominated cross-border claims (net of intra-euro area cross-border claims) stood at nearly $5 trillion, or 21% of the global aggregate (Table 1). The only currency with a higher global share is the US dollar, accounting for around $13 trillion (or 55% of the global total).

The share of euro-denominated cross-border claims varies considerably by borrowing region (Table 1). For advanced European countries outside the euro area, the euro share in cross-border bank lending (32%) is almost equal to that of the US dollar (35%). In emerging Europe, the share of euro-denominated claims (40%) exceeds that of US dollar claims (31%). By contrast, non-European EMEs borrow only a small fraction in euros (6.5%).

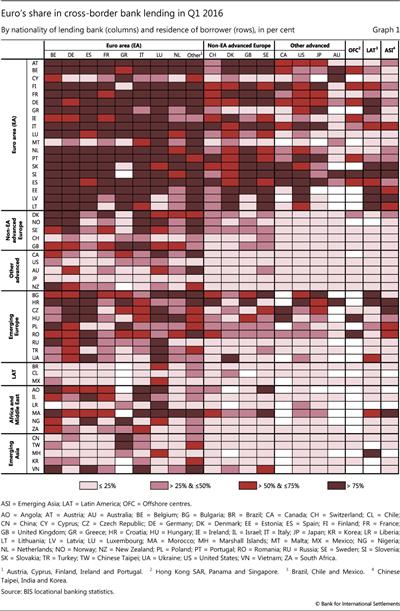

As discussed in the previous section, the enhanced BIS IBS contain information on the nationality of lending bank in addition to the country of the borrower and the currency of denomination.3 These more granular breakdowns indicate that the regional aggregates in Table 1 conceal even greater differences at the individual country level across both lending banking systems and borrowing countries. To illustrate these variations, we present a global "heat map" of the euro's shares in bilateral cross-border lending (Graph 1). The colour coding of each cell reflects the euro's share of cross-border claims between a particular lending banking system (columns) on a particular borrowing country (rows).

Following the reasoning outlined above, we aggregate the lending banks in Graph 1 based on their nationality, rather than on their residence. To see the empirical relevance of this distinction, consider the column for UK-owned banks. Only 2% of their claims on Japan are denominated in euros. By contrast, the corresponding share for banks located in the United Kingdom is much larger, at 22%. The large difference between the two respective shares is due mainly to the United Kingdom's role as a large global financial centre that hosts many banks headquartered in the euro area, which differ from UK-owned banks (Shin (2016)). This difference illustrates the fallacy of the "triple coincidence" in international finance - the traditional analytical framework that treats a GDP area, financial decision-making unit and currency area as identical (McCauley et al (2010), Shin (2012) and Avdjiev et al (2015b)).

Graph 1 reveals that, although the majority of global cross-border bank lending is denominated in US dollars, there is a clearly defined euro network comprising mainly the euro area and emerging Europe. Most of the claims originating from European banks or directed towards (advanced and emerging) European borrowers tend to be denominated in euros.

Cross-border bank lending before and after the 2015 ECB QE announcement

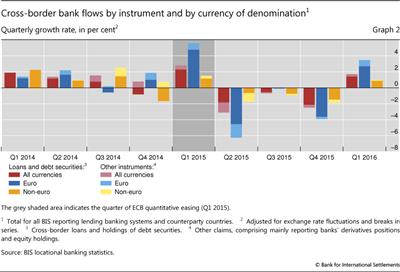

The growth rate of cross-border claims rose considerably during the quarter of the ECB QE announcement. In Q4 2014, the quarter preceding the ECB QE announcement, cross-border bank claims declined by 0.1% (Graph 2).4 In Q1 2015, the quarter of the January 2015 ECB QE announcement, cross-border claims grew by 2.8%. Euro-denominated claims grew much faster (5.6%) than claims denominated in other currencies (1.5%).

The size of the wedge between the growth rates of euro and non-euro claims in Q1 2015 varied considerably across borrower groups. The gap was especially large for claims on non-European advanced economies (10.2% for euro claims versus 1.4% for non-euro claims) and non-euro area European advanced economies (8.3% for euro claims versus 2.2% for non-euro claims). By contrast, claims on EMEs contracted at roughly the same pace in both currency segments (-0.5% for euro claims versus-1.6% for non-euro claims).

The overall $791 billion increase in cross-border claims during Q1 2015 was boosted by a $145 billion rise in "other claims", which capture primarily reporting banks' derivatives positions and equity holdings. That said, the overwhelming majority of the overall increase ($657 billion) was due to a surge in banks' cross-border loans and holdings of debt securities.5

The surge in cross-border bank lending that took place in Q1 2015 was followed by a contraction in the subsequent quarter. Nevertheless, a large portion of the $881 billion overall decline in claims during Q2 2015 was due to a $359 billion fall in "other claims" (BIS (2015)). On net, banks' cross-border loans and holdings of debt securities still recorded a sizeable ($141 billion) expansion during the first half of 2015.

Empirical analysis

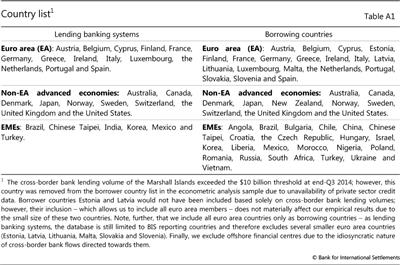

In selecting the sample for our analysis, we aim to include all internationally relevant national banking systems on the lending side and the main borrowing countries. On the lending side, we select 28 major national banking systems, which together accounted for 95% of all outstanding cross-border claims in the BIS locational data at end-Q1 2016. On the borrower side, we follow the framework of Avdjiev and Takáts (2014, 2016) and include 51 recipient countries whose cross-border bank borrowing exceeded $10 billion at end-Q3 2014 (see the detailed list of countries in the Annex Table A1).6 Finally, to abstract from claims for which the lender and the borrower are both from the same currency jurisdiction (ie the euro area), we exclude the cross-border claims of euro area banks on euro area borrowers (EA-on-EA claims) from our econometric analysis.

Potential drivers

To control for as many lender and borrower characteristics as possible, we examine a benchmark empirical specification, which includes a broad set of potential explanatory variables.

Our key explanatory variable of interest is the share of euro-denominated claims, which could have affected cross-border bank lending through several channels. First, a monetary loosening by the ECB should ease financing conditions in euros both within and outside the euro area. This would tend to lower banks' funding costs. To the extent that lower funding costs in a given currency translate into higher lending, this would stimulate cross-border bank credit. Second, the euro share could have made an impact through the international risk-taking channel of monetary policy (Rey (2015) and Bruno and Shin (2015b)). The euro's depreciation, triggered by a loosening monetary policy shock, would lift the net worth and the (perceived) creditworthiness of borrowers with euro liabilities and local currency assets. This would, in turn, increase banks' willingness to lend to such borrowers, ultimately lifting cross-border bank lending flows. A third channel may have worked through the hedging demand of institutional investors, who are likely to have been prompted to insure against further euro depreciation as a result of the ECB's QE announcement.

In addition to the euro share, we also include the change in the bilateral exchange rate (of the borrower's local currency against the euro) and its interaction with the euro share variable due to the key role that the euro exchange rate plays in a couple of the above channels.

Following Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012), we also control for strategic considerations. More precisely, we create variables that measure (a) the strategic importance of each borrowing country for each lending banking system; and (b) the importance of each lending banking system for each borrowing country. We define (a) as the share of cross-border claims that lending banking system X has allocated to borrowing country Y, and (b) as the share of cross-border bank claims on borrowing country Y from lending banking system X.

In addition, we include four control variables on the lending banking system side: the changes in the average bank CDS spreads and bank equity prices during the ECB QE quarter, as well as the domestic credit growth and deposit growth. We also examine five borrowing country variables: GDP growth, growth of credit to the private sector, current account balance, the government budget balance and government debt.

These factors might work differently in EMEs, which tend to have weaker balance sheets or fewer sophisticated domestic institutional investors. We control for these differences by introducing an EME borrower dummy and its interactions with the euro share and with the borrowing country-specific controls.

Benchmark specification

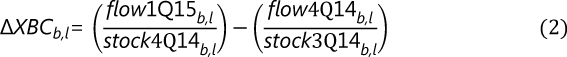

The data structure and the timing of the ECB QE announcement guide our regression setup. The IBS are reported at a quarterly frequency and the ECB QE was announced in January 2015. In our benchmark specification we therefore compare the growth in cross-border bank claims in Q1 2015 against their growth in Q4 2014.

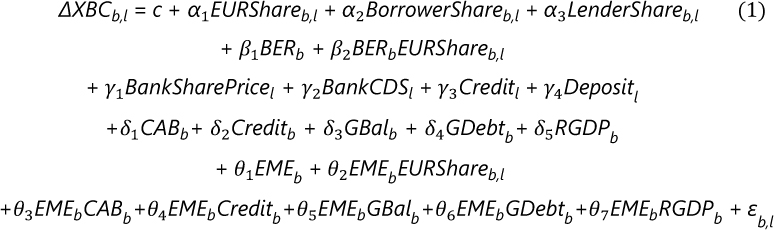

We start with a regression that includes all the candidate explanatory variables discussed in the previous section. Formally, we estimate the following equation:

Our dependent variable ΔXBCb,l represents the change in the growth rate, ie the acceleration (adjusted for exchange rates and breaks in series) of lending banking system l's cross-border claims on borrowing country b between the ECB QE quarter (Q1 2015) and the preceding quarter (Q4 2014). Formally:

Our independent variables are defined as follows: c is a constant; EURShareb,l is the share of euro-denominated cross-border bank claims of lending banking system l on borrowing country b (as of end-December 2014, in percent); BorrowerShareb,l measures the importance of each borrowing location b for each lending banking system l in terms of cross-border claims in all currencies (as of end-September 2014, in percent); LenderShareb,l measures the importance of each lending nationality l for each borrowing location b in terms of cross-border claims in all currencies (as of end-September 2014, in percent); BERb is the percentage change in the bilateral exchange rate (of the borrower's local currency against the euro) between end-Q4 2014 and end-Q1 2015, where a positive change indicates appreciation of the local currency of borrowing country b vis-à-vis the euro; BankSharePricel is the bank equity price growth in the home country of the lending banking system l between Q4 2014 and Q1 2015 (in percent); BankCDSl is the change in US dollar-denominated five-year bank CDS spreads in the home country of the lending banking system l between Q4 2014 and Q1 2015 (in basis points); Creditl is the average annual real bank credit growth to the private non-financial sector in the home country of lending banking system l during the year preceding Q4 2014 (in percent); Depositsl is real deposit growth for lending banking system l in 2014 (in percent); CABb is the 2014 current account balance of borrowing country b (in percent of GDP); Creditb is the real bank credit growth to the private non-financial sector in the borrowing country b during the three years preceding Q4 2014 (cumulative, in percent); GBalb is the 2014 general government budget balance of borrowing country b (in percent of GDP); GDebtb is the 2014 general government gross debt of borrowing country b (in percent of GDP); RGDPb is the real GDP growth in borrowing country b in Q1 2015 (quarter-on-quarter, in percent); EMEb is a dummy for borrowers in emerging markets and ɛb,l is an error term.

As smaller volumes tend to be highly volatile (plausibly reflecting shocks that are more idiosyncratic), we weight each observation b,l by the size of the respective bilateral stock of outstanding cross-border claims.7 In order to reduce the effect of possibly spurious excessive outliers, we also winsorise (ie limit the extreme values of) our dependent variable (ie the change in the growth rate of cross-border bank lending) at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

Main results

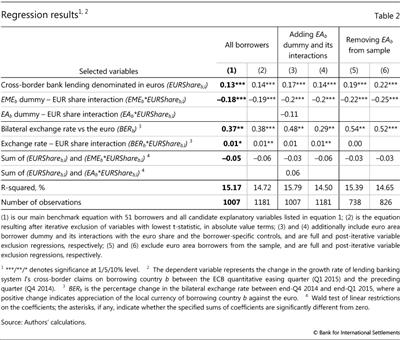

The benchmark regression results indicate that the share of euro lending in a given bilateral lending relationship prevailing prior to the ECB QE operations had a highly statistically significant positive impact on cross-border bank lending (Table 2, column 1, in bold). On average, a 10 percentage point higher euro share on the eve of the 2015 ECB QE was associated with an acceleration in cross-border bank lending growth of 1.3 percentage points during Q1 2015 (ie the ECB announcement quarter). The above relationship between the euro share and cross-border bank lending during Q1 2015 did not hold for EMEs. There, the impact of the euro exposure (ie the sum of the standalone euro share and the euro share-EME interaction term coefficients) was not statistically significant.

Next, we examine whether eliminating variables that are not statistically significant from the benchmark regression alters the main results (Table 2, column 2). We start by running a regression that includes all candidate explanatory variables discussed in the previous section. Then we exclude the variable with the lowestt-statistic (in absolute value terms). Next, we re-run the regression with the remaining variables. We continue this iterative procedure until all remaining explanatory variables are statistically significant at the 10% level. The results from the post-elimination regression show that the coefficients on the main euro share variables remain virtually unchanged.

Potential explanations

There are several potential explanations for our main findings. First, our results could reflect that a loosening of monetary policy in a given currency typically eases financing conditions in that currency, tending to lower banks' funding costs. To the extent that lower funding costs in a given currency translate into higher lending in that currency, cross-border bank credit would increase. And the size of the overall increase would naturally depend on the share of lending in that currency.

Second, the results could also be driven by the international risk-taking channel of monetary policy (Rey (2015) and Bruno and Shin (2015a)). When a global funding currency (such as the US dollar or the euro) depreciates, the effect is to increase the net worth of foreign borrowers (ie borrowers based outside the respective currency area) with currency mismatches on their balance sheets. This improves their perceived creditworthiness and ultimately lifts cross-border bank lending flows.

The third possible explanation for our main results is related to the hedging demands of institutional investors with currency mismatches on their balance sheets (Borio et al (2016) and Sushko et al (2016)). When a central bank (such as the ECB) in charge of a global funding currency signals an upcoming loosening of its monetary policy stance, the hedging demands of such investors tend to increase (Shin (2016)). This increase in hedging demand is typically met via FX swaps from internationally active banks, which would sell euros spot and buy euros forward from the institutional investor. The spot leg of the above transaction would show up as a euro loan on the balance sheet of the reporting bank. Moreover, if the reporting bank borrows the euros that it provides in the spot leg of the above transaction from another bank located in a different country, this would lead to a further increase in the cross-border interbank lending activity.8

The second and the third possible explanations for the statistical significance of the euro share apply only to borrowers outside the euro area. To the degree these channels are at work, one could expect that the estimated impact of the euro share would be larger for borrowers outside the euro area. We examine this hypothesis by estimating two additional specifications of our main regression. In the first, we add a dummy variable for euro area borrowers (Table 2, columns 3 and 4). In the second, we exclude euro area borrowers from the sample altogether (Table 2, columns 5 and 6). In all of these additional specifications, the euro share not only remains highly statistically significant, but also increases considerably in magnitude. These results could be interpreted as evidence in support of the second and the third explanations.

In the meantime, some clues about the relative likelihood of the above explanations emanate from the fact that our results are primarily driven by lending to (non-euro area) advanced economies and tend to be insignificant for lending to EME borrowers. Namely, the regional patterns in our results make the second explanation less likely since the international risk-taking channel of monetary policy tends to be stronger for EME borrowers than for borrowers in advanced economies. By contrast, they strengthen the case for the third potential explanation, since institutional investors, and their respective hedging demands, tend to be much larger in advanced economies than in EMEs.

Nevertheless, the above reasoning provides only tentative hints about the relative weight of the contributions of each of the above explanations. Properly identifying and quantifying those factors would certainly require a substantial amount of further research.

Robustness

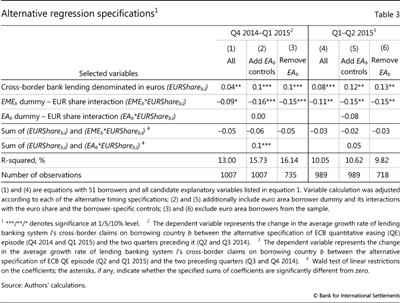

We start our robustness checks with specifications that alter the timing in the regression framework. First, we consider the build-up of QE expectations prior to the official announcement. Although the official ECB QE announcement was made in January 2015, senior ECB officials had given strong hints about the launch of the programme on multiple occasions in the latter part of 2014. As a consequence, the euro exchange rate had started to decline well ahead of the official announcement.

To examine this possible expectation effect, we re-estimate the benchmark regression on an earlier and longer time window that compares the period between end-September 2014 and end-March 2015 with the period between end-March 2014 and end-September 2014 (Table 3, column 1). Furthermore, we perform additional robustness checks of the analysis for this alternative window by inserting a dummy variable for euro area borrowers (Table 3, column 2) and by excluding euro area borrowers from the regression (Table 3, column 3). Even though the euro share coefficients become a bit smaller relative to the benchmark window, they retain their sign and statistical significance.

Another potential timing concern is related to the partial reversal of flows in Q2 2015. It is possible that the positive impact of the euro share detected in Q1 2015 was wiped out in the subsequent quarter. To test this, we re-estimate the benchmark regression on an extended time period. Namely, we compare the growth rates of cross-border bank claims during the period Q1-Q2 2015 with those from Q3-Q4 2014. We start by re-running our benchmark specification for this alternative window (Table 3, column 4). We then repeat the analysis while inserting a dummy variable for euro area borrowers (Table 3, column 5) and while excluding euro area borrowers (Table 3, column 6). Again, the euro share coefficients decline slightly relative to their counterparts from the benchmark window, but remain positive and strongly statistically significant.

We also show that excluding explanatory variables, one at a time, does not materially affect the euro share results.9 The euro share coefficient remains positive and significant at the 1% level in all specifications. The euro share interaction term with EMEs becomes insignificant in only one case, when dropping borrowing country credit. Most importantly, the extensive control for EME behaviour that we apply in our benchmark model does not drive the significant euro share coefficient estimates: even when dropping the EME dummy and all EME interaction terms, the euro share coefficient estimate remains positive and highly significant.

Finally, we also check that our results do not depend on outliers. Hence, we systematically exclude, one by one, each lending banking system and each borrowing country. The results remain robust to these exclusions. The euro share coefficient remains highly significant in all cases.

Conclusion

This special feature provides evidence that the currency denomination of cross-border bank claims was a significant driver of the cross-sectional variation in cross-border bank lending in response to the January 2015 ECB QE announcement. More concretely, higher shares of euro-denominated claims were associated with greater expansions in cross-border bank lending. This result appears to be driven primarily by lending to advanced economies outside the euro area. By contrast, the estimated effects on cross-border lending to EME borrowers tend to be insignificant.

The findings suggest that the US dollar network, which has been the main focus of the existing literature on the topic, is not unique. The euro cross-border bank lending network responds to monetary policy shocks in a qualitatively similar manner. Furthermore, the reactions of currency networks to an easing monetary policy shock (such as the 2015 ECB QE announcement) are symmetric to their response to a tightening monetary policy shock (such as the 2013 Fed taper tantrum).

The results are particularly relevant for policymakers in borrowing countries that rely heavily on cross-border bank lending. They suggest that credit supply depends not only on the health of lending banking systems (as already documented in the existing literature), but also on the currency denomination of cross-border bank lending. For example, euro lending by Swiss banks to Poland can be affected by the ECB's monetary policy, even though neither country is part of the euro area. Given the extraordinary monetary policies implemented by central banks in advanced economies over the past few years and the large stocks of cross-border loans denominated in foreign currencies, our findings suggest that policymakers should closely monitor the currency denomination of cross-border bank lending as they assess the potential impact of possible policy moves, both in their own economies and abroad.

References

Avdjiev, S, P McGuire and P Wooldridge (2015a): "Enhanced data to analyse international banking", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 53-68.

Avdjiev, S, R McCauley and H S Shin (2015b): "Breaking free of the triple coincidence in international finance", BIS Working Papers, no 524, October.

Avdjiev, S and E Takáts (2014): "Cross-border bank lending during the taper tantrum: the role of emerging market fundamentals", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 49-60.

--- (2016): "Monetary policy spillovers and currency networks in cross-border bank lending", BIS Working Papers, March, no 549.

Bank for International Settlements (2015): "Highlights of the BIS international statistics", BIS Quarterly Review, December, pp 13-25.

Borio, C, R McCauley P McGuire and V Sushko (2016): "Covered interest parity lost: understanding the cross-currency basis", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 45-64.

Bruno, V and H S Shin (2015a): "Cross-border banking and global liquidity", Review of Economic Studies, vol 82, no 2, pp 535-64.

--- (2015b): "Capital flows and the risk-taking channel of monetary policy", Journal of Monetary Economics, no 71, pp 119-32.

Cecchetti, S, I Fender and P McGuire (2010): "Towards a global risk map", BIS Working Papers, no 309, May.

Cetorelli, N and L Goldberg (2012): "Liquidity management of US global banks: internal capital markets in the great recession", Journal of International Economics, vol 88, no 2, pp 299-311.

Fender, I and P McGuire (2010): "Bank structure, funding risks and the transmission of shocks across countries: concepts and measurement", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 63-79.

Forbes, K and F Warnock (2012): "Capital flow waves: surges, stops, flight and retrenchment", Journal of International Economics, vol 88, no 2, pp 235-51.

McCauley, R, P McGuire and V Sushko (2015): "Global dollar credit: links to US monetary policy and leverage", Economic Policy, vol 30, no 82, April, pp 187-229; also BIS Working Papers, no 483, January.

McCauley, R, P McGuire and G von Peter (2010): "The architecture of global banking: from international to multinational?", BIS Quarterly Review, March, pp 25-37.

Rey (2015): "International channels of transmission of monetary policy and the Mundellian Trilemma", IMF Economic Policy Review, forthcoming.

Shin, H S (2012): "Global banking glut and loan risk premium", Mundell-Fleming Lecture, IMF Economic Review, vol 60, no 2, pp 155-92, July.

--- (2015): "Exchange rates and the transmission of global liquidity", speech at the Bank of Korea-IMF conference, "Leverage in Asia: lessons from the past, what's new now? And where to watch out for?", Seoul, 11 December.

--- (2016): "Global liquidity and procyclicality", speech at the World Bank conference, "The state of economics, the state of the world", Washington DC, 8 June.

Sushko, V, C Borio, R McCauley and P McGuire (2016): "Whatever happened to covered interest parity? Hedging demand meets limits to arbitrage", BIS Working Papers, forthcoming.

Annex

1 The authors thank Claudio Borio, Ben Cohen, Dietrich Domanski, Robert McCauley, Patrick McGuire and Hyun Song Shin for useful comments and discussions. Pamela Pogliani provided excellent assistance with the data from the BIS international banking statistics. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the BIS.

2 Previously, the BIS IBS data illuminated only two of the above three dimensions. The consolidated data set gave the nationality of the lending banks (dimension A) and the borrower's residence (dimension B), but provided no currency breakdown (dimension C). By contrast, the locational data did reveal the currency composition of banks' cross-border claims (dimension C), but not the borrower's residence (dimension B, locational by nationality) or the nationality of the lending bank (dimension A, locational by residence).

3 Using the enhanced IBS, we can simultaneously identify the nationality of the lending bank, the country of the borrower and the currency of denomination for approximately 90% of the global stock of cross-border bank claims outstanding at the end of Q1 2016.

4 These quarterly changes, like the others discussed in this feature, are corrected for exchange rate changes and breaks in series.

5 The breakdown by instrument (loans vs debt securities vs "other instruments") in the above paragraph is obtained from the BIS locational banking statistics by residence (LBSR). The amounts reported in loans, debt securities and "other instruments" do not add up exactly to the total for all instruments due to the fact that a small fraction of total claims is unallocated by instrument. Unfortunately, an instrument breakdown is not available in the BIS locational banking statistics by nationality (LBSN). That is why, in our benchmark empirical analysis, which uses the LBSN dataset, we focus on banks' total claims rather than on banks' loans and holdings of debt securities.

6 In the specifications that include euro area borrowers, we include all euro area countries regardless of whether they pass the above threshold. This provides us with a consistently defined (de facto) control group, which helps us isolate the effect on cross-border lending to borrowers outside the euro area.

7 More specifically, the weight that we assign to each observation is equal to the square root of cross-border claims that lending banking system l had on borrowing country b in total cross-border bank lending as of end-September 2014 (the weight variable is not shown in equation (1) to ease the overview).

8 Note that the above effect would be present even if the reporting bank is located in the same country as the institutional investor whose hedging demand it accommodates. In this case, the spot leg of the FX swap transaction would show up as an increase in the net local currency assets of the reporting bank. Nevertheless, to the extent that the borrowing bank would need to borrow the euros from another (related or unrelated) bank located in a different country, this would still result in an increase in cross-border interbank claims.

9 When removing an explanatory variable, we also remove the interaction terms in which it enters.