In search of a new compass

Abstract

The global economy has shown encouraging signs over the past year. But its malaise persists, as the legacy of the Great Financial Crisis and the forces that led up to it remain unresolved. To overcome that legacy, policy needs to go beyond its traditional focus on the business cycle. It also needs to address the longer-term build-up and run-off of macroeconomic risks that characterise the financial cycle and to shift away from debt as the main engine of growth. Restoring sustainable growth will require targeted policies in all major economies, whether or not they were hit by the crisis. Countries that were most affected need to complete the process of repairing balance sheets and implementing structural reforms. The current upturn in the global economy provides a precious window of opportunity that should not be wasted. In a number of economies that escaped the worst effects of the financial crisis, growth has been spurred by strong financial booms. Policy in those economies needs to put more emphasis on curbing the booms and building the strength to cope with a possible bust, and there, too, it cannot afford to put structural reforms on the back burner. Looking further ahead, dampening the extremes of the financial cycle calls for improvements in policy frameworks - fiscal, monetary and prudential - to ensure a more symmetrical response across booms and busts. Otherwise, the risk is that instability will entrench itself in the global economy and room for policy manoeuvre will run out.

Full text

The global economy continues to face serious challenges. Despite a pickup in growth, it has not shaken off its dependence on monetary stimulus. Monetary policy is still struggling to normalise after so many years of extraordinary accommodation. Despite the euphoria in financial markets, investment remains weak. Instead of adding to productive capacity, large firms prefer to buy back shares or engage in mergers and acquisitions. And despite lacklustre long-term growth prospects, debt continues to rise. There is even talk of secular stagnation.

Why is this so? To understand these dynamics, we need to go back to the Great Financial Crisis. The crisis that erupted in August 2007 and peaked roughly one year later marked a defining moment in economic history. It was a watershed, both economically and intellectually: we now naturally divide developments into pre- and post-crisis. It cast a long shadow into the past: the crisis was no bolt from the blue, but stemmed almost inevitably from deep forces that had been at work for years, if not decades. And it cast a long shadow into the future: its legacy is still with us and shapes the course ahead.

Understanding the current global economic challenges requires a long-term perspective. Such a perspective should extend well beyond the time span of the output fluctuations ("business cycles") that dominate economic thinking. As conceived and measured, these business cycles play out over no more than eight years. This is the reference time frame for most macroeconomic policy, the one that feeds policymakers' impatience at the slow pace of economic recovery and that helps to answer questions on how quickly output might be expected to return to normal or how long it might deviate from its trend. It is the time frame in which the latest blips in industrial production, consumer and business confidence surveys or inflation numbers are scrutinised in search of clues about the economy.

But this time frame is too short. Financial fluctuations ("financial cycles") that can end in banking crises such as the recent one last much longer than business cycles. Irregular as they may be, they tend to play out over perhaps 15 to 20 years on average. After all, it takes a lot of tinder to light a big fire. Yet financial cycles can go largely undetected. They are simply too slow-moving for policymakers and observers whose attention is focused on shorter-term output fluctuations.

The fallout from the financial cycle can be devastating. When financial booms turn to busts, output and employment losses may be huge and extraordinarily long-lasting. In other words, balance sheet recessions levy a much heavier toll than normal recessions. The busts reveal the resource misallocations and structural deficiencies that were temporarily masked by the booms. Thus, when policy responses fail to take a long-term perspective, they run the risk of addressing the immediate problem at the cost of creating a bigger one down the road. Debt accumulation over successive business and financial cycles becomes the decisive factor.

This year's BIS Annual Report explores this long-term perspective.1 In taking stock of the global economy, it sets out a framework in which the crisis, the policy response to it and its legacy take centre stage. The long-term view complements the more traditional focus on shorter-term fluctuations in output, employment and inflation - one in which financial factors may play a role, but a peripheral one.

The bottom line is simple. The global economy has shown many encouraging signs over the past year. But it would be imprudent to think it has shaken off its post-crisis malaise. The return to sustainable and balanced growth may remain elusive.

The restoration of sustainable growth requires broad-based policies. In crisis-hit countries, there is a need to put more emphasis on balance sheet repair and structural reforms and relatively less on monetary and fiscal stimulus: the supply side is crucial. Good policy is less a question of seeking to pump up growth at all costs than of removing the obstacles that hold it back. The upturn in the global economy is a precious window of opportunity that should not be wasted. In economies that escaped the worst effects of the financial crisis and have been growing on the back of strong financial booms, there is a need to put more emphasis on curbing those booms and building strength to cope with a possible bust. Warranting special attention are new sources of financial risks, linked to the rapid growth of capital markets. In these economies also, structural reforms are too important to be put on the back burner.

There is a common element in all this. In no small measure, the causes of the post-crisis malaise are those of the crisis itself - they lie in a collective failure to get to grips with the financial cycle. Addressing this failure calls for adjustments to policy frameworks - fiscal, monetary and prudential - to ensure a more symmetrical response across booms and busts. And it calls for moving away from debt as the main engine of growth. Otherwise, the risk is that instability will entrench itself in the global economy and room for policy manoeuvre will run out.

The first section takes the pulse of the global economy. The second interprets developments through the lens of the financial cycle and assesses the risks ahead. The third develops the policy implications.

The global economy: where do we stand?

The good news is that growth has picked up over the past year and the consensus is for further improvement (Chapter III). In fact, global GDP growth is projected to approach the rates prevailing in the pre-crisis decade. Advanced economies (AEs) have been gaining momentum even as their emerging counterparts have lost some.

On balance, though, the post-crisis period has been disappointing. By the standards of normal business cycles, the recovery has been slow and weak in crisis-hit countries. Unemployment there is still well above pre-crisis levels, even if it has recently retreated. Emerging market economies (EMEs) have stood out as the main engines of post-crisis growth, rebounding strongly after the crisis until the recent weakening. Overall, while global GDP growth is not far away from the rates seen in the 2000s, the shortfall in the GDP path persists. We have not made up the lost ground.

Moreover, the longer-term outlook for growth is far from bright (Chapter III). In AEs, especially crisis-hit ones, productivity growth has disappointed during the recovery. And this comes on top of a longer-term trend decline. So far, productivity has held up better in economies less affected by the crisis and especially in EMEs, where no such long-term decline is generally evident. That said, demographic headwinds are blowing strongly, and not only in the more mature economies.

What about inflation? In a number of EMEs, it is still a problem. But by and large, it has stayed low and stable - this is good news. At the same time, in some crisis-hit jurisdictions and elsewhere, inflation has been persistently below target. In some cases, new concerns have been voiced about deflation, notably in the euro area. This raises the question, discussed below, of how much one should worry.

On the financial side, the picture is one of sharp contrasts.

Financial markets have been exuberant over the past year, at least in AEs, dancing mainly to the tune of central bank decisions (Chapter II). Volatility in equity, fixed income and foreign exchange markets has sagged to historical lows. Obviously, market participants are pricing in hardly any risks. In AEs, a powerful and pervasive search for yield has gathered pace and credit spreads have narrowed. The euro area periphery has been no exception. Equity markets have pushed higher. To be sure, in EMEs the ride has been much rougher. At the first hint in May last year that the Federal Reserve might normalise its policy, emerging markets reeled, as did their exchange rates and asset prices. Similar tensions resurfaced in January, this time driven more by a change in sentiment about conditions in EMEs themselves. But market sentiment has since improved in response to decisive policy measures and a renewed search for yield. Overall, it is hard to avoid the sense of a puzzling disconnect between the markets' buoyancy and underlying economic developments globally.

The financial sector's health has improved, but scars remain (Chapter VI). In crisis-hit economies, banks have made progress in raising capital, largely through retained earnings and new issues, under substantial market and regulatory pressure. That said, in some jurisdictions doubts linger about asset quality and how far balance sheets have been repaired. Not surprisingly, the comparative weakness of banks has supported a major expansion of corporate bond markets as an alternative source of funding. Elsewhere, in many countries less affected by the crisis and on the back of rapid credit growth, balance sheets look stronger but have started to deteriorate in some cases.

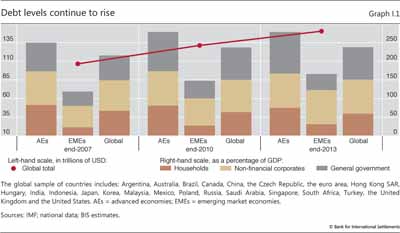

Private non-financial sector balance sheets have been profoundly affected by the crisis and pre-crisis trends (Chapter IV). In crisis-hit economies, private sector credit expansion has been slow, but debt-to-GDP ratios generally remain high, even if they have come down in some countries. At the other end of the spectrum, several economies that escaped the crisis, particularly EMEs, have seen credit and asset price booms which have only recently started to slow. Globally, the total debt of private non-financial sectors has risen by some 30% since the crisis, pushing up its ratio to GDP (Graph I.1).

Particularly worrying is the limited room for manoeuvre in macroeconomic policy.

Fiscal policy remains generally under strain (Chapter III). In crisis-hit economies, fiscal deficits ballooned as revenues collapsed, economies received emergency stimuli and, in some cases, the authorities rescued banks. More recently, several countries have sought to consolidate. Even so, government debt-to-GDP ratios have risen further; in several cases, they appear to be on an unsustainable path. In countries that were not hit by the crisis, the picture is more mixed, with debt-to-GDP ratios in some cases actually falling, in others rising but from much lower levels. The combined public sector debt of the G7 economies has grown by close to 40 percentage points, to some 120% of GDP in the post-crisis period - a key factor behind the 20 percentage point increase in total (public plus private sector) debt-to-GDP ratios globally (Graph I.1).

Monetary policy is testing its outer limits (Chapter V). In the crisis-hit economies and Japan, monetary policy has been extraordinarily accommodative. With policy rates at or close to the zero lower bound in all the main international currencies, central banks have eased further by adopting forward guidance and aggressive balance sheet policies such as large-scale asset purchases and long-term lending. Never before have central banks tried to push so hard. The normalisation of the policy stance has hardly started. In other countries, post-crisis interest rates have also been quite low and central banks have vigorously expanded their balance sheets, in this case reflecting foreign exchange interventions. Mainly as a result of the market turbulence, several EME central banks have raised rates in the past year.

The overall impression is that the global economy is healing but remains unbalanced. Growth has picked up, but long-term prospects are not that bright. Financial markets are euphoric, but progress in strengthening banks' balance sheets has been uneven and private debt keeps growing. Macroeconomic policy has little room for manoeuvre to deal with any untoward surprises that might be sprung, including a normal recession.

The global economy through the financial cycle lens

How did we get here? And what are the macroeconomic risks ahead? To understand the journey, we need to study the nature of the past recession and the subsequent policy response.

A balance sheet recession and its aftermath

The prologue to the Great Recession is well known. A major financial boom developed against the backdrop of low and stable inflation, turbocharged, as so often in past such episodes, by financial innovation. Credit and property prices soared, shrugging off a shallow recession in the early 2000s and boosting economic growth once more (Chapter IV). Spirits ran high. There was talk of a Great Moderation - a general sense that policymakers had finally tamed the business cycle and uncovered the deepest secrets of the economy.

The recession that followed shattered this illusion. As the financial boom turned to bust, a financial crisis of rare proportions erupted. Output and world trade collapsed. The ghost of the Great Depression loomed large.

The policy response was haunted by that ghost. To be sure, the first signs of trouble were misread. When interbank markets froze in August 2007, the prevailing view was that the stress would remain contained. But matters changed when Lehman Brothers failed roughly one year later and the global economy hit an air pocket. Both monetary and fiscal policies were used aggressively to avoid a repeat of the 1930s experience. This echoed well beyond the countries directly hit by the crisis, with China embarking on a massive credit-fuelled expansion.

At first, the medicine seemed to work. Counterfactual statements are always hard to make. But no doubt the prompt policy response did cushion the blow and forestall the worst. In particular, an aggressive monetary policy easing in crisis-hit economies restored confidence and prevented the financial system and the economy from plunging into a tailspin. This is what crisis management is all about.

Even so, as events unfolded, relief gave way to disappointment. The global economy did not recover as hoped. Growth forecasts, at least for crisis-hit economies, were repeatedly revised downwards. Fiscal policy expansion failed to jump-start the economy. In fact, gaping holes opened up in the fiscal accounts. And in the euro area, partly because of the institutional specificities, a sovereign crisis erupted in full force, threatening a "doom loop" between weak banks and sovereigns. Globally, concerns with fiscal unsustainability induced a partial change of fiscal course. In the meantime, in an effort to boost the recovery, monetary policy continued to experiment with ever more imaginative measures. And regulatory authorities struggled to rebuild the financial system's strength. The global economy was not healing.

With hindsight at least, this sequence of events should not be surprising. The recession was not the typical postwar recession to quell inflation. This was a balance sheet recession, associated with the bust of an outsize financial cycle. As a result, the debt and capital stock overhangs were much larger, the damage to the financial sector far greater and the room for policy manoeuvre much more limited.

Balance sheet recessions have two key features.

First, they are very costly (Chapter III). They tend to be deeper, give way to weaker recoveries, and result in permanent output losses: output may return to its previous long- term growth rate but hardly to its previous growth path. No doubt, several factors are at work. Booms make it all too easy to overestimate potential output and growth as well as to misallocate capital and labour. And during the bust, the overhangs of debt and capital stock weigh on demand while an impaired financial system struggles to oil the economic engine, damaging productivity and further eroding long-term prospects.

Second, as growing evidence suggests, balance sheet recessions are less responsive to traditional demand management measures (Chapter V). One reason is that banks need to repair their balance sheets. As long as asset quality is poor and capital meagre, banks will tend to restrict overall credit supply and, more importantly, misallocate it. As they lick their wounds, they will naturally retrench. But they will keep on lending to derelict borrowers (to avoid recognising losses) while cutting back on credit or making it dearer for those in better shape. A second, even more important, reason is that overly indebted agents will wish to pay down debt and save more. Give them an additional unit of income, as fiscal policy would do, and they will save it, not spend it. Encourage them to borrow more by reducing interest rates, as monetary policy would do, and they will refuse to oblige. During a balance sheet recession, the demand for credit is necessarily feeble. The third reason relates to the large sectoral and aggregate imbalances in the real sector that build up during the preceding financial boom - in construction, for instance. Boosting aggregate demand indiscriminately does little to address them. It may actually make matters worse if, for example, very low interest rates favour sectors where too much capital is already in place.

To be sure, only part of the world went through a full balance sheet recession (Chapter III). The countries that did so experienced outsize domestic financial cycles, including, in particular, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain and Ireland, together with many countries in central and eastern Europe and the Baltic region. There, debt overhangs in the household and non-financial company sectors went hand in hand with systemic banking problems. Other countries, such as France, Germany and Switzerland, experienced serious banking strains largely through their banks' exposures to financial busts elsewhere. The balance sheets of their private non-financial sectors were far less affected. Still others, such as Canada and many EMEs, were exposed to the crisis largely through trade linkages, not through their banks; their recessions were not of the balance sheet variety. This was also true of Japan, a country that has been struggling under the weight of a protracted demand shortfall linked to demography; its own balance sheet recession was back in the 1990s: this hardly explains the country's more recent travails. And only in the euro area did a "doom loop" between banks and sovereigns break out.

This diversity also explains why countries now find themselves in different positions in their domestic financial cycles (Chapter IV). Those that experienced full balance sheet recessions have struggled to manage down their overhangs of private debt amid falling property prices. That said, some of them are already seeing renewed increases in property prices while debt levels are still high, and in some cases growing. Elsewhere, the picture varies, but credit and property prices have generally continued to rise post-crisis, at least until recently. In some countries, the pace of financial expansion has remained within typical historical ranges. But in others it has gone well beyond, resulting in strong financial booms.

In turn, the financial booms in this latter set of countries reflect in no small measure the interplay of monetary policy responses (Chapters II, IV and V). Extraordinarily easy monetary conditions in advanced economies have spread to the rest of the world, encouraging financial booms there. They have done so directly, because currencies are used well beyond the borders of the country of issue. In particular, there is some $7 trillion in dollar-denominated credit outside the United States, and it has been growing strongly post- crisis. They have also done so indirectly, through arbitrage across currencies and assets. For example, monetary policy has a powerful impact on risk appetite and risk perceptions (the "risk-taking channel"). It influences measures of risk appetite, such as the VIX, as well as term and risk premia, which co-move strongly worldwide - a factor that has gained prominence as EMEs have deepened their fixed income markets. And monetary policy responses in non-crisis-hit countries have also played a role. Authorities there have found it hard to operate with interest rates that are significantly higher than those in the large crisis-hit jurisdictions for fear of exchange rate overshooting and of attracting surges in capital flows.

As a result, for the world as a whole monetary policy has been extraordinarily accommodative for unusually long (Chapter V). Even excluding the impact of central banks' balance sheet policies and forward guidance, policy rates have remained well below traditional benchmarks for quite some time.

Current macroeconomic and financial risks

Seen through the financial cycle lens, the current configuration of macroeconomic and financial developments raises a number of risks.

In the countries that have been experiencing outsize financial booms, the risk is that these will turn to bust and possibly inflict financial distress (Chapter IV). Based on leading indicators that have proved useful in the past, such as the behaviour of credit and property prices, the signs are worrying. Debt service ratios appear somewhat less worrisome, but past experience suggests that they can surge before distress emerges. This is especially so if interest rates spike, as might happen if it became necessary to defend exchange rates under pressure from large unhedged foreign exchange exposures and/or monetary policy normalisation in AEs.

Moreover, compared with the past, specific vulnerabilities may have changed in unsuspected ways (Chapter IV). Over the past few years, non-financial corporations in a number of EMEs have borrowed heavily through their foreign affiliates in the capital markets, with the debt denominated mainly in foreign currency. This has been labelled the "second phase of global liquidity", to differentiate it from the pre-crisis phase, which was largely centred on banks expanding their cross-border operations. The corresponding debt may not show up in external debt statistics or, if the funds are repatriated, it may show up as foreign direct investment. It could represent a hidden vulnerability, especially if backed by domestic currency cash flows derived from overextended sectors, such as property, or used for carry trades or other forms of speculative position-taking.

Likewise, the asset management industry's burgeoning presence in EMEs could amplify asset price dynamics under stress (Chapters IV and VI). This is especially the case in fixed income markets, which have grown strongly over the past decade, further exposing the countries concerned to global capital market forces. Like an elephant in a paddling pool, the huge size disparity between global investor portfolios and recipient markets can amplify dislocations. It is far from reassuring that these flows have swelled on the back of an aggressive search for yield: strongly procyclical, they surge and reverse as conditions and sentiment change.

To be sure, many EMEs have taken important steps to improve resilience over the years. In contrast to the past, these countries have posted current account surpluses, built up foreign exchange reserves, increased the flexibility of their exchange rates, strengthened their financial systems and adopted a plethora of macroprudential measures. Indeed, in the two episodes of market strains in May 2013 and January 2014, it was the countries with stronger macroeconomic and financial conditions that fared better (Chapter II).

Even so, past experience suggests caution. The market strains seen so far have not as yet coincided with financial busts; rather, they have resembled traditional balance of payments tensions. To cushion financial busts, current account surpluses may help, but only up to a point. In fact, historically some of the most damaging financial booms have occurred in countries with strong external positions. The United States in the 1920s, ahead of the Great Depression, and Japan in the 1980s are just two examples. And macroprudential measures, while useful to strengthen banks, have on their own proved unable to effectively constrain the build-up of financial imbalances, especially where monetary conditions have remained accommodative (Chapters V and VI). Time and again, in both advanced and emerging market economies, seemingly strong bank balance sheets have turned out to mask unsuspected vulnerabilities that surface only after the financial boom has given way to bust (Chapter VI).

This time round, severe financial stress in EMEs would be unlikely to leave AEs unscathed. The heft of EMEs has grown substantially since their last major reverse, the 1997 Asian crisis. Since then, their share has risen from around one third to half of world GDP, at purchasing power parity exchange rates. And so has their weight in the international financial system. The ramifications would be particularly serious if China, home to an outsize financial boom, were to falter. Especially at risk would be the commodity-exporting countries that have seen strong credit and asset price increases and where post-crisis terms-of-trade gains have shored up high debt and property prices. And so would those areas in the world where balance sheet repair is not yet complete.

In crisis-hit economies, the risk is that balance sheet adjustment remains incomplete, in both the private and the public sectors. This would increase their vulnerability to any renewed economic slowdown, regardless of its source, and it would hinder policy normalisation. Indeed, in the large economies furthest ahead in the business cycle, notably the United States and United Kingdom, it is somewhat unsettling to see growth patterns akin to those observed in later stages of financial cycles, even though debt and asset prices have not yet fully adjusted (Chapter IV). For example, property prices have been unusually buoyant in the United Kingdom, and segments of the corporate lending market, such as leveraged transactions, have been even frothier than they were before the crisis in the United States (Chapter II). Reflecting incomplete adjustment, in both cases private sector debt service ratios appear highly sensitive to increases in interest rates (Chapter IV). Meanwhile, especially in the euro area, doubts persist about the strength of banks' balance sheets (Chapter VI). And all this is occurring at a time when, almost everywhere, fiscal positions remain fragile when assessed from a longer-term perspective.

Policy challenges

On the basis of this analysis, what should be done now? Designing the near-term policy response requires taking developments in the business cycle and inflation into account, which can give rise to awkward trade-offs. And how should policy frameworks adjust longer-term?

Near-term challenges: what is to be done now?

The appropriate near-term policy responses, as always, have to be country-specific. Even so, at some risk of oversimplification, it is possible to offer a few general considerations by dividing countries into two sets: those that have experienced a financial bust and those that have been experiencing financial booms. It is then worth exploring a challenge that cuts across both groups: what to do where inflation has been persistently below objectives.

Countries that have experienced a financial bust

In the countries that have experienced a financial bust, the priority is balance sheet repair and structural reform. This proceeds naturally from three features of balance sheet recessions: the damage from supply side distortions, the lower responsiveness to aggregate demand policies and the much narrower room for policy manoeuvre, be this fiscal, monetary or prudential. The objective is to lay the basis for a self-sustaining and robust recovery, to remove the obstacles to growth and to raise growth potential. This holds out the best hope of avoiding chronic weakness. Policymakers should not waste the window of opportunity that a strengthening economy affords.

The first priority is to complete the repair of the banks' balance sheets and to shore up those of the non-financial sectors most affected by the crisis. Disappointingly, despite all efforts so far, banks' stand-alone ratings - which strip out external support - have actually deteriorated post-crisis (Chapter VI). But countries where policymakers have done more to enforce loss recognition and recapitalise, such as the United States, have also recovered more strongly. This is nothing new: before the recent crisis, the contrasting ways in which the Nordic countries and Japan dealt with their banking crises in the early 1990s were widely regarded as an important factor behind the subsequent divergence in their economic performance. The European Union's forthcoming asset quality review and stress tests are crucial in achieving this objective. More generally, banks should be encouraged to further improve their capital strength - the most solid basis for further lending (Chapter VI). The completion of the post-crisis financial reforms, of which Basel III is a core element, is vital.

This suggests that failure to repair balance sheets can sap the longer-term output and growth potential of an economy (Chapter III). Put differently, what economists call "hysteresis" - the impact on productive potential of the persistence of temporary conditions - comes in various shapes and sizes. Commonly, hysteresis effects are seen as manifesting themselves through chronic shortfalls in aggregate demand. In particular, the unemployed lose their skills, thus becoming less productive and employable. But there are also important, probably dominant, effects that operate through misallocations of credit and other resources as well as inflexible markets for goods, labour and capital. These are hardly mentioned in the literature but deserve more attention. As a corollary, in the wake of a balance sheet recession, the allocation of credit matters more than its aggregate amount. Given the debt overhangs, it is not surprising that, as empirical evidence indicates, post-crisis recoveries tend to be "credit-less". And even if overall credit fails to grow strongly on a net basis, it is important that good borrowers obtain it rather than bad ones.

Along with balance sheet repair, targeted structural reforms will also be important. Structural reforms play a triple role (Chapter III). First, they can facilitate the required resource transfers across sectors, so critical in the aftermath of balance sheet recessions, thereby countering economic weakness and speeding up the recovery (see last year's Annual Report). For instance, it is probably no coincidence that the United States, where labour and product markets are quite flexible, has rebounded more strongly than continental Europe. Second, reforms will help raise the economy's sustainable growth rate in the longer term. Given adverse demographic trends, and aside from higher participation rates, raising productivity growth is the only way to boost long-term growth. And finally, through both mechanisms, reforms can assure firms that demand will be there in future, thus boosting it today. Although fixed business investment is not weak globally, where it is weak the constraint is not tight financial conditions. The mix of structural policies will necessarily vary according to the country. But it will frequently include deregulating protected sectors, such as services, improving labour market flexibility, raising participation rates and trimming public sector bloat.

More emphasis on repair and reform implies relatively less on expansionary demand management.

This principle applies to fiscal policy. After the initial fiscal push, the need to ensure longer-term sustainability has been partly rediscovered. This is welcome: putting the fiscal house in order is paramount; the temptation to stray from this path should be resisted. Whatever limited room for manoeuvre exists should be used, first and foremost, to help repair balance sheets, using public funds as backstops of last resort. A further use, where the need is great, could be to catalyse private sector financing for carefully chosen infrastructure projects (Chapter VI). Savings on other budgetary items may be needed to make room for these priorities.

And the same principle also applies to monetary policy. More intensive repair and reform efforts would help relieve the huge pressure on monetary policy. While some monetary accommodation is no doubt necessary, excessive demands have been made on it post-crisis. The limitations of policy become especially acute when rates approach zero (Chapter V). At that point, the only way to provide additional stimulus is to manage expectations about the future path of the policy rate and to use the central bank's balance sheet to influence financial conditions beyond the short-term interest rate. These policies do have an impact on asset prices and markets, but have clear limits and diminishing returns. Term and risk premia can only be compressed up to a point, and in recent years they have already reached or approached historical lows. To be sure, exchange rate depreciation can help. But, as discussed further below, it also raises awkward international issues, especially if it is seen to have a beggar-thy-neighbour character.

The risk is that, over time, monetary policy loses traction while its side effects proliferate. These side effects are well known (see previous Annual Reports). Policy may help postpone balance sheet adjustments, by encouraging the evergreening of bad debts, for instance. It may actually damage the profitability and financial strength of institutions, by compressing interest margins. It may favour the wrong forms of risk-taking. And it can generate unwelcome spillovers to other economies, particularly when financial cycles are out of synch. Tellingly, growth has disappointed even as financial markets have roared: the transmission chain seems to be badly impaired. The failure to boost investment despite extremely accommodative financial conditions is a case in point (Chapter III).

This raises the issue of the balance of risks concerning when and how fast to normalise policy (Chapter V). In contrast to what is often argued, central banks need to pay special attention to the risks of exiting too late and too gradually. This reflects the economic considerations just outlined: the balance of benefits and costs deteriorates as exceptionally accommodative conditions stay in place. And political economy concerns also play a key role. As past experience indicates, huge financial and political economy pressures will be pushing to delay and stretch out the exit. The benefits of unusually easy monetary policies may appear quite tangible, especially if judged by the response of financial markets; the costs, unfortunately, will become apparent only over time and with hindsight. This has happened often enough in the past.

And regardless of central banks' communication efforts, the exit is unlikely to be smooth. Seeking to prepare markets by being clear about intentions may inadvertently result in participants taking more assurance than the central bank wishes to convey. This can encourage further risk-taking, sowing the seeds of an even sharper reaction. Moreover, even if the central bank becomes aware of the forces at work, it may be boxed in, for fear of precipitating exactly the sharp adjustment it is seeking to avoid. A vicious circle can develop. In the end, it may be markets that react first, if participants start to see central banks as being behind the curve. This, too, suggests that special attention needs to be paid to the risks of delaying the exit. Market jitters should be no reason to slow down the process.

Countries where financial booms are under way or turning

In the countries less affected by the crisis and that have been experiencing financial booms, the priority is to address the build-up of imbalances, which could threaten financial and macroeconomic stability. This task is a pressing one. As shown in May last year, the eventual normalisation of US policy could trigger renewed market tensions (Chapter II). The window of opportunity should not be missed.

The challenge for these countries is to seek ways to curb the boom, and to strengthen defences against any eventual financial bust. First, prudential policy should be tightened, especially through the use of macroprudential tools. Monetary policy should work in the same direction while fiscal measures should preserve enough room for manoeuvre to deal with any turn in the cycle. And, just as elsewhere, the authorities should take advantage of today's relatively favourable climate to implement needed structural reforms.

The dilemma for monetary policy is especially acute. So far, policymakers have relied mostly on macroprudential measures to dampen financial booms. These measures have no doubt strengthened the financial system's resilience, but their effectiveness in constraining the booms has been mixed (Chapter VI). Debt burdens have increased, as has the economy's vulnerability to higher policy rates. After rates have stayed so low for so long, the room for manoeuvre has narrowed (Chapter IV). Particularly for countries in the late stages of financial booms, the trade-off is now between the risk of bringing forward the downward leg of the cycle and that of suffering a bigger bust later on. Earlier, more gradual adjustments are preferable.

Interpreting recent disinflation

In recent years, a number of countries have experienced unusually and persistently low inflation or even an outright fall in prices. In some cases, this has occurred alongside sustained output growth and even some worrying signs that financial imbalances are building up. One example is Switzerland, where prices have actually been gradually declining while the mortgage market booms. Another is found in some Nordic countries, where inflation has sagged below target and output performance has been a bit weaker. The most notorious instance of long-lasting price declines is Japan, where prices started to fall after the financial bust in the 1990s and continued to edge down until recently, albeit by a mere 4 percentage points cumulatively. More recently, concerns have been expressed about low inflation in the euro area.

In deciding how to respond, it is important to carefully assess the factors driving prices and their persistence as well as to take a critical look at the effectiveness and possible side effects of the available tools (Chapters III and V). For instance, there are grounds for believing that the forces of globalisation are still exerting some welcome downward pressure on inflation. Pre-crisis, this helped central banks to keep inflation at bay even as financial booms developed. And when policy rates have fallen to the effective zero lower bound, and the headwinds of a balance sheet recession persist, monetary policy is not the best tool for boosting demand and hence inflation. Moreover, damaging perceptions of competitive depreciations can arise, given that in a context of generalised weakness the most effective channel for raising output and prices is to depreciate the exchange rate.

More generally, it is essential to discuss the risks and costs of falling prices in a dispassionate way. The word "deflation" is extraordinarily charged: it immediately raises the spectre of the Great Depression. In fact, the Great Depression was the exception rather than the rule, in the intensity of both its price declines and the associated output losses (Chapter V). Historically, periods of falling prices have often coincided with sustained output growth. And the experience of more recent decades is no exception. Moreover, conditions have changed substantially since the 1930s, not least with regard to downward wage flexibility. This is no reason to be complacent about the risks and costs of falling prices: they need to be monitored and assessed closely, especially where debt levels are high. But it is a reason to avoid knee-jerk reactions prompted by emotion.

Longer-term challenges: adjusting policy frameworks

The main long-term challenge is to adjust policy frameworks so as to promote healthy and sustainable growth. This means two interrelated things.

The first is to recognise that the only way to sustainably strengthen growth is to work on structural reforms that raise productivity and build the economy's resilience. This is an old and familiar problem (Chapter III). As noted, the decline in productivity growth in advanced economies took hold a long time ago. To be sure, as economies mature, part of this may be the natural result of shifts in demand patterns towards sectors where measured productivity is lower, such as services. But part is surely the result of a failure to embark on ambitious reforms. The temptation to postpone adjustment can prove irresistible, especially when times are good and financial booms sprinkle the fairy dust of illusory riches. The consequence is a growth model that relies too much on debt, both private and public, and which over time sows the seeds of its own demise.

The second, more novel, challenge is to adjust policy frameworks so as to address the financial cycle more systematically. Frameworks that fail to get the financial cycle on the radar screen may inadvertently overreact to short-term developments in output and inflation, generating bigger problems down the road. More generally, asymmetrical policies over successive business and financial cycles can impart a serious bias over time and run the risk of entrenching instability in the economy. Policy does not lean against the booms but eases aggressively and persistently during busts. This induces a downward bias in interest rates and an upward bias in debt levels, which in turn makes it hard to raise rates without damaging the economy - a debt trap. Systemic financial crises do not become less frequent or intense, private and public debts continue to grow, the economy fails to climb onto a stronger sustainable path, and monetary and fiscal policies run out of ammunition. Over time, policies lose their effectiveness and may end up fostering the very conditions they seek to prevent. In this context, economists speak of "time inconsistency": taken in isolation, policy steps may look compelling but, as a sequence, they lead policymakers astray.

As discussed, there are signs that this may well be happening. The room for policy manoeuvre is shrinking even as debt continues to rise. And looking back, it is not hard to find instances in which policy appeared to focus too narrowly on short-term developments. Consider the response to the stock market crashes of 1987 and 2000 and the associated economic slowdowns (Chapter IV). Policy, especially monetary policy, eased strongly in both cases to cushion the blow and was tightened only gradually thereafter. But the financial boom, in the form of credit and property price increases, gathered momentum even as the economy softened, responding in part to the policy easing. The financial boom then collapsed a few years later, causing aggravated financial stress and economic harm. Paradoxically, the globalisation of the real economy added strength and breadth to the financial booms: it raised growth expectations, thus turbocharging the booms, while keeping a lid on prices, thereby lessening the need to tighten monetary policy.

This also has implications for how to interpret the downward trend of interest rates since the 1990s. Some observers see this decline as reflecting deeper forces that generate a chronic shortfall in demand. On this interpretation, policy has passively responded to such forces, thus preventing greater economic damage. But this analysis indicates that policies with a systematic easing bias can be an important factor in themselves, as they interact with the destructive force of the financial cycle. Interest rates are hindered from returning to more normal levels by the accumulation of debt, together with the distortions in production and investment patterns associated with those same unusually low interest rates. In effect, low rates validate themselves. By threatening to weaken balance sheets still further, the looming downward pressure on asset prices linked to negative demographic trends can only exacerbate this process.

What would it take to adjust policy frameworks? The required adjustments concern national frameworks as well as the way they interact internationally.

The overall strategy for national policy frameworks should be to ensure that buffers are built up during a financial boom so that they can be drawn down in the bust. Such buffers would make the economy more resilient to a downturn. And, by acting as a kind of sea anchor, they could also dampen the boom's intensity. Their effect would be to make policy less procyclical by rendering it more symmetrical with respect to the boom and bust phases of the financial cycle. This would avoid a progressive loss of policy room for manoeuvre over time.

For prudential policy, this means strengthening the framework's systemic or macroprudential orientation. Available instruments, such as capital requirements or loan-to-value ratios, need to be adjusted to reduce procyclicality. For monetary policy, this means being ready to tighten whenever financial imbalances show signs of building up, even if inflation appears to be under control in the near term. And for fiscal policy, it means extra caution when assessing fiscal strength during financial booms, and taking remedial action. It also means designing a tax code that does not favour debt over equity.

Following the crisis, policies have indeed moved in this direction, but to varying degrees. And there is still more to do.

Prudential policy is furthest ahead. In particular, Basel III has introduced a countercyclical capital buffer for banks as part of a broader trend towards establishing national macroprudential frameworks.

Monetary policy has shifted somewhat. It is now generally recognised that price stability does not guarantee financial stability. Moreover, a number of central banks have adjusted their frameworks to incorporate the option of tightening during booms. A key element has been to lengthen policy horizons. That said, no consensus exists as to whether such adjustments are desirable. And the side effects of prolonged and aggressive easing after the bust continue to be debated.

Fiscal policy lags furthest behind. There is little recognition of the huge flattering effect that financial booms have on the fiscal accounts: they cause potential output and growth to be overestimated (Chapter III), are particularly generous to the fiscal coffers, and mask the build-up of contingent liabilities needed to address the consequences of the busts. During their booms, for example, Ireland and Spain could point to declining government debt-to-GDP ratios and to fiscal surpluses that turned out, after all, not to be properly adjusted for the cycle. Similarly, there is scant appreciation of the limitations of an expansionary fiscal policy during a balance sheet recession; indeed, the prevailing view is that fiscal policy is more effective under such conditions.

For monetary policy, the challenges are especially tough. The basic idea is to lengthen the policy horizon beyond the two years or so that central banks typically focus on. The idea is not to mechanically extend point forecasts, of course. Rather, it is to permit a more systematic and structured assessment of the risks that the slower-moving financial cycles pose to macroeconomic stability, inflation and the effectiveness of policy tools. Concerns about the financial cycle and inflation would also become easier to reconcile: the key is to combine an emphasis on sustainable price stability with greater tolerance for short-run deviations from inflation objectives as well as for exchange rate appreciation. Even so, the communication challenges are daunting.

Turning to the interaction of national policy frameworks, the challenge is to tackle the complications that ensue from a highly integrated global economy. In such a world, the need for collective action - cooperation - is inescapable. National policies, taken individually, are less effective. And incentive problems abound: national policymakers may be tempted to free-ride, or they may come under political pressure to disregard the unwelcome impact of their policies on others.

Cooperation is continuously tested; it advances and retreats. Post-crisis, it has advanced considerably in the fields of financial regulation and fiscal affairs. Witness the overhaul of financial regulatory frameworks, most notably Basel III and the efforts coordinated by the Financial Stability Board, as well as the recent initiatives on taxation under the aegis of the G20. In these areas, the need for cooperation has been fully recognised.

By contrast, in the monetary field the own-house-in-order doctrine still dominates: as argued in more detail elsewhere,2 there is clearly room for improvement. The previous discussion indicates that the interaction of national monetary policies has raised risks for the global economy. These are most vividly reflected in what have been extraordinarily accommodative monetary and financial conditions for the world as a whole, and in the build-up of financial imbalances within certain regions. At a minimum, there is a need for national authorities to take into account the effects of their actions on other economies and the corresponding feedbacks on their own jurisdictions. No doubt, the larger economies already seek to do this. But if their analytical frameworks do not place financial booms and busts at the centre of the assessments and if they fail to take into account the myriad of financial interconnections that hold the global economy together, these feedback effects will be badly underestimated.

Conclusion

The global economy is struggling to step out of the shadow of the Great Financial Crisis. The legacy of the crisis is pervasive. It is evident in the comparatively high levels of unemployment in crisis- hit economies, even as output growth has regained strength, in the disconnect between extraordinarily buoyant financial markets and weak investment, in the growing dependence of financial markets on central banks, in rising private and public debt, and in the rapidly narrowing policy room for manoeuvre.

This chapter has argued that a return to healthy and sustainable global growth requires adjustments to the current policy mix and to policy frameworks. These adjustments should acknowledge that the post- crisis balance sheet recession is less amenable to traditional aggregate demand policies and puts a premium on balance sheet repair and structural reforms, that financial booms and busts have become a major threat to macroeconomic stability, and that the only source of lasting prosperity is a stronger supply side, notably higher productivity growth. And they should be based on the premise that, in a highly integrated global economy, keeping one's own house in order is necessary but not sufficient for prosperity: for this, international cooperation is essential.

In the near term, the main task is to take advantage of the window of opportunity presented by the current pickup in world growth. There is a need to rely relatively less on traditional aggregate demand stimulus and more on balance sheet repair and structural reforms, especially in crisis-hit economies. Monetary policy, in particular, has been overburdened for too long. After so many years of an exceptional monetary expansion, the risk of normalising too slowly and too late deserves special attention. And, where applicable, the response to surprising disinflationary pressures needs to carefully take into account the nature and persistence of the forces at work, diminished policy effectiveness and its side effects. In countries experiencing strong financial booms, the priority is to strengthen defences to face a potential bust. There, too, structural reforms should not be delayed.

In the longer term, the main task is to adjust policy frameworks so as to make growth less debt-dependent and to tame the destructive power of the financial cycle. More symmetrical macroeconomic and prudential policies over that cycle would avoid a persistent easing bias that, over time, can entrench instability and exhaust the policy room for manoeuvre.

The risks of failing to act should not be underestimated. The global economy may be set on an unsustainable path. And at some point, the current open global trade and financial order could be seriously threatened. So far, institutional setups have proved remarkably resilient to the huge shock of the financial crisis. But we should not take this for granted, especially if serious financial stress were to resurface. The intermittent noise about "currency wars" is particularly worrying: where domestic expansionary policies do not work as expected, exchange rate depreciation may come to be seen as the only option. But competitive easing can be a negative sum game when everyone tries to use this weapon and the domestic costs of the policies exceed their benefits. Also worrying is the growing temptation for nation states to withdraw from the laborious but invaluable task of fostering international integration.

Meanwhile, the consensus on the merits of price stability is fraying at the edges. And, as memories of the costs and persistence of inflation fade, the temptation could grow to void the huge debt burdens through a combination of inflation, financial repression and autarky.

There is a lot of work to do. A new policy compass is conspicuously lacking. This introductory chapter has outlined the broad direction of travel. Major analytical and operational challenges remain to be solved if policies are to adequately address financial booms and busts. Some of the possible tools are described in the pages that follow, but much more needs to be done. And the political economy challenges are even more daunting. As history reminds us, there is little appetite for taking the long-term view. Few are ready to curb financial booms that make everyone feel illusively richer. Or to hold back on quick fixes for output slowdowns, even if such measures threaten to add fuel to unsustainable financial booms. Or to address balance sheet problems head-on during a bust when seemingly easier policies are on offer. The temptation to go for shortcuts is simply too strong, even if these shortcuts lead nowhere in the end.

The road ahead may be a long one. All the more reason, then, to start the journey sooner rather than later.

1 See also J Caruana, "Global economic and financial challenges: a tale of two views", lecture at the Harvard Kennedy School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 9 April 2014; and C Borio, "The financial cycle and macroeconomics: what have we learnt?", BIS Working Papers, no 395, December 2012 (forthcoming in Journal of Banking & Finance).

2 J Caruana, "International monetary policy interactions: challenges and prospects", speech at the CEMLA-SEACEN conference on The role of central banks in macroeconomic and financial stability: the challenges in an uncertain and volatile world, Punta del Este, Uruguay, 16 November 2012.