Carlos da Silva Costa: Portugal - reform and growth within the euro area

Opening speech by Mr Carlos da Silva Costa, Governor of the Bank of Portugal, at the Bank of Portugal-International Monetary Fund conference "Portugal - Reform and Growth within the Euro Area", Lisbon, 25 March 2019.

The views expressed in this speech are those of the speaker and not the view of the BIS.

As prepared for delivery.

Good morning,

It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to our joint conference with the International Monetary Fund on the paths for reform in Portugal, as a euro area member.

Growth periods like the one we are currently in involve a greater propensity to take on excessive risk and to postpone structural reforms. We also know regulation tends to be procyclical, meaning that it is loosened when it should be tightened and vice versa. This is why it is crucial in the current environment to bear in mind the lessons from the last crisis and, above all, to prevent the resurgence of the factors that led up to it.

With this in mind, I think now is an important time to speak about:

- the process leading up to the crisis that hit the Portuguese economy,

- the adjustment initiated with the financial assistance programme, and

- the current challenges to sustainable growth.

Before the assistance programme

The process that led Portugal to the most recent assistance programme started in the mid-1990s, in a context of broad internal and external balance.

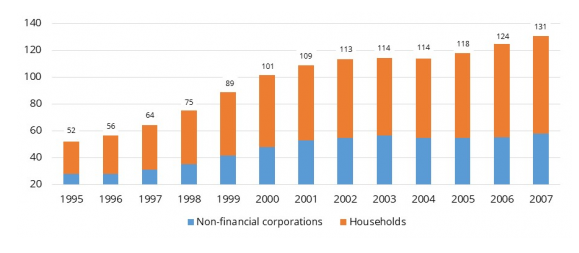

Financial liberalisation and the prospect of joining the euro made financing cheaper and more accessible, bringing about a strong credit expansion and a fall in the household savings rate. Between 1995 and 2007, credit to the private sector, measured as a percentage of GDP, almost tripled from 52% to 131%. During the same period, the household savings rate almost halved, reaching 7% in 2007. The largest slice of credit was channelled to financing consumption and low-return investments, largely in non-tradable sectors.

Credit to the private sector grew much faster than GDP

Loans to non-financial corporations and households, as percentage of GDP

Source: Banco de Portugal

In parallel, the rise of Asian competition in the low-technology sectors and the challenge posed by the enlargement of the EU to Central and Eastern European Countries, which captured foreign direct investment in the medium-technology sectors, brought difficulties to Portuguese exports. Such reshuffling of comparative advantages had a bearing on the performance of firms operating in the tradable sector.

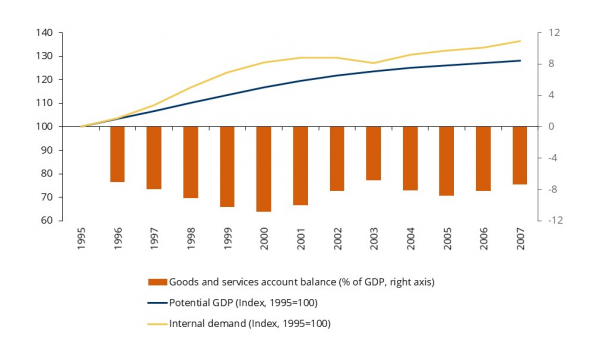

As a result of these different shocks, Portugal lost export market share in international markets, imports grew and the current account deficit deteriorated, without a corresponding expansion of the economy's growth potential. Between the mid-1990s and the eve of the global financial crisis in 2007, the Portuguese current and capital account went from near balance to a deficit of 8.6% of GDP, whereas gross external debt rose from approximately 60% to 195% of GDP. At the same time, annual potential growth declined from around 3% to just below 1%.

Domestic demand grew faster than potential output, contributing to external deficits

Source: Banco de Portugal and Statistics Portugal

External indebtedness was to a large extent intermediated by the Portuguese banking system. Banks raised (mostly short-term) funds in the euro money market and converted them into (long-term) loans to the private sector, creating an important maturity mismatch in their balance sheets. The loan-to-deposit ratio for the whole banking system rose from 89% in 1998 to 156% in 2007.

A macroprudential policy and a countercyclical fiscal policy would have helped contain the risks associated with the expansion of domestic demand. However, macroprudential policy was simply not part of the standard toolbox and the mostly pro-cyclical fiscal policy that was followed aggravated the macroeconomic imbalances. In the period from 1995 to 2007, the budget deficit averaged 4.3% of GDP, and was always above the Maastricht threshold of 3% of GDP.

When the international financial crisis broke, the weak potential output growth and rising external indebtedness fuelled investors' doubts about the capacity of Portuguese economic agents to pay their debts. Between 2009 and 2011, external financing to banks fell by around 30 percentage points of GDP. As a result, banks had to turn to the Eurosystem, whilst at the same time the volume of Portuguese sovereign debt placed with domestic banks increased.

In the first half of 2011, following twelve months in which interest rates on ten-year government debt had almost doubled to just over 9%, mounting doubts among investors about the sustainability of the public finances and external debt lead to a shutdown of access to international funding markets. Recourse to external financial assistance became unavoidable, under a programme negotiated with the European Union and the International Monetary Fund.

This was not the first time Portugal had to resort to official financial assistance. As many here in the audience will remember well, we had already negotiated adjustment programmes with the IMF in 1977-1978 and 1983.

The root cause of the accumulated imbalances was then essentially the same: excessive domestic demand growth in relation to the productive capacity of the economy, leading to external debt accumulation.

However, given that we were not part of a monetary union and had full monetary autonomy in the 1970s and 1980s, the symptoms of the crisis and the policy prescriptions produced at the time show some important differences when compared to the most recent crisis episode.

In a context of monetary sovereignty, the imbalances translated into currency depreciation, international reserves depletion and high and rising inflation rates.

With monetary policy fully available at national level, financial repression was the name of the game. The policy prescription consisted of interest rate increases, credit growth targets, capital controls and the devaluation of the escudo to contain domestic demand and restore export competitiveness.

As a result of the adjustment strategy, the real value of wages, pensions and savings declined sharply and wealth was transferred from creditors to debtors. Money illusion blurred the perception of the adjustment costs and of the fundamentally unbalanced burden-sharing. Also, as nominal variables were targeted and competitiveness was restored in the short term, structural supply-side imbalances and long-term competitiveness failed to be properly addressed. As a consequence, the country's competitiveness remained fragile and anchored in low wages.

In the first decade of the 2000s, being part of a monetary union facilitated a longer and larger accumulation of imbalances. Nominal stability, low interest rates and ample credit availability created the illusion that credit constraints had disappeared and masked persistent losses of competitiveness for more than a decade.

The symptoms of the emerging crisis no longer included persistent exchange rate pressure, reserve depletion or high and rising inflation, but rather a sudden unwillingness on the part of international investors to finance the Portuguese economy.

Without the monetary instrument, money illusion was no longer there and the policy prescription had to be different. As a result, the need for deleveraging and structural supply-side reforms became inescapable.

The financial assistance programme

The execution of the economic and financial assistance programme set out in 2011 brought about noteworthy progress:

- The budget deficit declined significantly, which created the conditions for the current downward trend of sovereign debt;

- the private sector initiated a deleveraging process; and

- the banking sector became more robust, with stronger liquidity, higher solvency and, in the most recent period, improved asset quality.

This success was based on three key factors:

- first, political ownership, socioeconomic awareness and social dialogue. Policymakers were committed to the programme's goals and showed deep knowledge of the virtuous response mechanisms to be activated in the critical sectors. On the other hand, the public understood the urgency and even-handedness of the programme. The political compromises achieved between policymakers and social partners were key to ensuring a broad and collective ownership of the programme, which in turn determined its effective and timely execution.

- second, the positive, intense and fast response by the export sector, which grew by around 45% in real terms between 2008 and 2017. This contributed to the correction of the current account deficit, to put external debt on a downward trajectory, and to mitigate the impact of lower domestic demand on the non-tradable sector. This positive response by the tradable sector was much stronger than expected and was not driven exclusively by foreign markets' growth, given that there were important market share gains during this period.

- third, the maintenance of the general public's confidence in the financial system, as evident in the consistent stability of aggregate deposits. This allowed the financing of the economic activity to proceed without major disruptions and prevented the resort to capital controls. The fear and deposit drain observed in other economies that were subject to assistance programmes did not occur in the Portuguese case. This was not by accident, since there was an active and persistent effort by the authorities to preserve confidence in the financial system throughout the implementation of the programme.

After the assistance programme

The macroeconomic adjustment initiated by the economic and financial assistance programme has continued after the programme ended in 2014, with encouraging results.

GDP has been growing at an average annual rate above 2%, reflecting the continued dynamism of the export sector and, more recently, the rebound of private investment. Fiscal consolidation proceeded, with the budget balance expected to be around -0.5% in 2018 and public debt entering a downward trend. The current and capital accounts were kept in surplus and the clean-up of banks' balance sheets has intensified, with NPLs declining from over 50 billion euro in June 2016 to about half this amount in end 2018.

Despite the undisputed progress, there is no room for complacency. The history of the past 40 years teaches us that the initial impact from an assistance programme will only be sustainable if there are structural changes that foster higher potential growth.

Over the recent past, Portuguese per capita GDP has remained 30-40% below the European Union average, without converging towards the richest economies. A lasting trajectory of growth and convergence towards our European partners depends on our ability:

- to promote efficient resource allocation, namely through sustained maximisation of investment returns, and reallocation towards the tradable sector;

- to reach higher levels of productivity;

- to generate and maintain high levels of employment; and

- to ensure that the combination of capital and labour generates an output that is desired and valued by the market.

Public policy has a key role to play by upholding continued structural reforms that will, inter alia, help:

- increase aggregate savings in the economy;

- strengthen firms' capitalisation;

- provide, through capital markets, adequate instruments to finance innovation and exports;

- promote regulatory and tax predictability and, more generally, a business-friendly legal framework;

- the separation between firm ownership and firm management;

- red tape reduction; and

- a better functioning of the judicial system.

Such reforms are, on the one hand, imperative for pursuing the correction of the macroeconomic imbalances that led Portugal to the past crises and, on the other hand, extremely hard to implement after the conclusion of the assistance programme.

Why do I say that structural reforms are extremely hard to implement in the current context? Let me highlight three critical challenges.

- First, in the current context of strong global competition, firms need to adapt permanently to the fast-changing competition, requiring accordingly adaptable support services by the State. This means that we need a State that is lean and efficient, while being able to safeguard social cohesion at the same time.

- Second, transferring resources towards the tradable sector is crucial for avoiding a return to external imbalances, but may jeopardise social cohesion. Indeed, adapting to competition is always challenging and there are losers in this process. These situations have to be supported by sustainable social safety nets.

- Finally, in the absence of a sense of emergency, of imminent financial market pressure and of money illusion, reform ownership by policymakers and social consensus become much harder. The costs from each reform become clearer and must be carefully balanced by perceived offsetting benefits.

The nature of these challenges transcends pure economic models, encompassing social equilibria. Overcoming them requires, thus, social and political consensus, only attainable through an open, broad and informed debate.

I am confident that this conference will contribute to such a debate and that by the end of the day we will have gained many useful insights into what paths to take for effective reform and the strategies to adopt in order to remove the obstacles in the way.

Thank you very much for being here.