Theodore Mitrakos: Normalisation of the monetary policy of major central banks and possible implications for the Club members' economies - the case of Greece

Speech by Mr Theodoros Mitrakos, Deputy Governor of the Bank of Greece, at the 38th meeting of the Central Bank Governors' Club of the Central Asia, Black Sea Region & Balkan countries, Bank of Russia, Moscow, 29 September 2017.

The views expressed in this speech are those of the speaker and not the view of the BIS.

It is a great pleasure for me to be here with you today and have the opportunity to exchange thoughts on the potential impact of the normalisation of monetary policy in our respective economies. My intervention comprises three parts. Part I provides an overview of non-standard monetary policy measures across the major central banks and looks at alternative paths to the normalisation of monetary policy. Part II sketches the benefits for Greece from the accommodative monetary policy. Part III presents the recent economic developments in Greece and some thoughts on the potential impact of monetary policy normalisation.

Part I: Normalisation of monetary policy across the major central banks

I.1 An overview of non-standard monetary policy measures

It has been almost 10 years since major central banks were forced to confront a worldwide financial crisis that ushered them into a new world of central banking. In response to the extraordinary environment, central banks have engaged in a range of ambitious unconventional/non-standard monetary policy measures, unprecedented in nature, scope and magnitude, including:

- large-scale asset purchases of government and private sector assets;

- near-zero or negative policy rates;

- forward guidance on both.

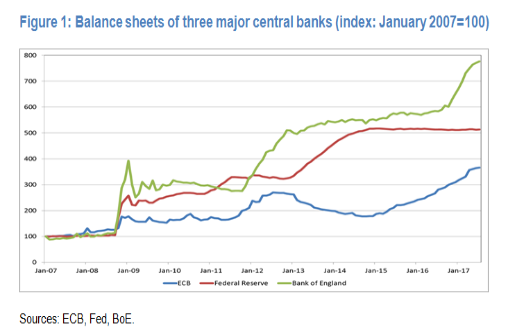

Asset purchases have resulted in a huge expansion of central bank balance sheets. Since the onset of the crisis in 2007, the Bank of England' s (BoE) balance sheet has grown seven-fold; the Federal Reserve's (Fed) five-fold, while that of the European Central Bank (ECB) has more than tripled. Combined, the balance sheets of the Fed, the Bank of England and the ECB now exceed $15 trillion, equivalent to almost 45 percent of their GDP.

I.2 ECB measures: Quantitative easing and other programmes

The European Central Bank (ECB) began its large-scale purchases of assets later than its peers. In March 2015, the ECB increased the degree of monetary policy accommodation by adding public sector securities to its purchase programmes (PSPP), which at the time encompassed covered bonds (CBPP3) and Asset-Backed Securities (ABSPP). In 2016, the programme was extended to include corporate bonds (CSPP).

Purchases of marketable debt instruments through the expanded asset purchase programme (EAPP) amounted, at the end of August 2017, to € 2.1tn. The largest part (€ 1.7 tn) is attributed to the public sector purchase programme (PSPP), while the amounts attributed to the third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3), the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP) and the asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP) stood at € 227 bn, € 107 bn and € 24 bn, respectively.

Furthermore, to stimulate bank lending to the real economy, the ECB also conducted a series of Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs). The take-up in the two series of the TLTRO operations has also been significant: total TLTRO drawings from euro area banks now stand at about €760 bn.

Looking at the breakdown of debt securities under PSPP by country, 60% of the cumulative monthly net purchases are accounted for by Germany, France and Italy. Also, around 11% of total purchases concern supranational bonds.

Regarding the effectiveness of the ECB stimulus programmes, they have:

- Contributed to a robust and rather broad based recovery:

- Eurozone growth is projected to reach 2.2 percent this year, its fastest rate in 10 years. Economic expansion has been ongoing for 17 consecutive quarters.

- The recovery is having a profound effect on the labour market: around 6.4 million jobs have been created since 2013.

- Added strong downward pressures on financing costs

- Rates have fallen steeply across asset classes, maturities and countries, as well as across different categories of borrowers.

- Lowered cross-country heterogeneity

- Dispersion of GDP and employment growth rates among euro area member states have fallen to record lows.

Nonetheless, the economic recovery has yet to translate into higher inflation:

- Euro area inflation has undershot 2 percent for the fifth consecutive year.

- It is expected to continue to undershoot the ECB target for some time - possibly through 2019.

- Measures of underlying inflation remain overall subdued and have yet to show convincing signs of a pick-up.

- The stronger euro is also exerting downward pressure on consumer prices. Since the start of the year, the euro has risen by about 14 per cent against the dollar.

I.3 Alternative paths to normalization and potential impact

Overall, the policies aiming to contain deflationary pressures have been effective in stabilising the financial system and thereby preventing a deep economic downturn.

Some ten years later, the world economy has entered a synchronised growth phase. All three of the world's economic powerhouses - North America, Europe and China - are growing in unison.

With the global recovery firming up and global inflation rising, some major central banks might now be looking to gradually reverse course. The key challenge for monetary policy is how to unwind this accommodation in the least disruptive manner in terms of inflation, output and financial market stability.

In terms of the broader alternative strategies to normalisation, the following paths could be envisaged:

- First seeking to guide policy rates higher, before initiating downward balance sheet adjustments (as in the United States);

- Starting to downsize the balance sheet before initiating a tightening of interest rates;

- Undertaking both in tandem.

The sequence in the implementation of balance sheet and interest rate measures, as well as the relative weights, could have a differing impact on the domestic economies, as well as cross-border spillovers, including through exchange rates and other financial channels.

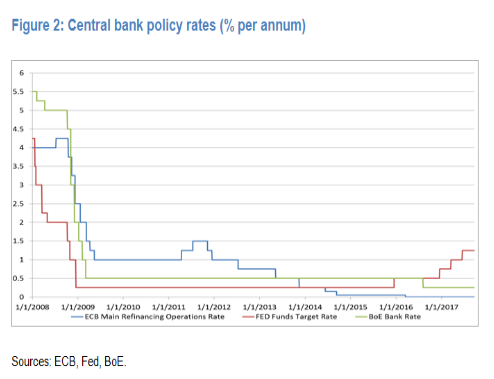

Looking at specific central banks, the continued discrepancy between strengthening economic activity and subdued inflation dynamics poses a puzzle for the monetary policy of the ECB. In the absence of sufficient evidence of progress towards a durable and self-sustaining convergence in the path of inflation, a scaling-back of the exceptional degree of monetary policy accommodation is not warranted. Deliberations on the future course of the ECB monetary policy are ongoing, especially regarding considerations about its asset purchase strategy beyond December 2017. Adjustments in the monetary policy stance should be prudent and gradual, so as to ensure that any withdrawal of stimulus does not undermine the recovery amid the lingering uncertainties. In this vein, clear and timely communication of the Governing Council's assessment is of utmost importance. Given that markets can be sensitive to incoming information, timely communication is key to avoiding an extreme reaction, or "taper tantrum", as experienced following the first announcements by the FED that it would taper its QE purchases back in 2013. The recent experience warrants caution. Even hints at policy normalisation may cause an unwarranted tightening in financial conditions, as evidenced by the market movements after the speech of President Draghi in Sintra on 27 June 2017.

Across the Atlantic, the Federal Reserve, has advanced in normalisation with four rate rises in 18 months, which have brought the target rate on the federal funds to 1.25 per cent, from a target of 0-0.25 per cent in the seven-year period to December 2015, and an announcement to cautiously start the normalisation of its balance sheet already in October this year.. Despite the -somewhat reluctant- tightening of the Fed, the US monetary policy could actually be assessed as still being rather loose. The global capital flows from the emerging markets that are invested in the US contribute to this easing.

Turning now to the Bank of England, in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum (summer 2016), the Bank cut its interest rate to a record low of 0.25% after more than 7 years of static interest rates. It also boosted its QE scheme, while committing extra funds to encourage banks to lend. The rhetoric however has become more aggressive over the past few months, notably due to surging inflation - brought on by the weakened pound since the referendum - despite a slowdown in the economy as the country prepares to leave the European Union. With respect to normalisation strategy, the Bank of England has in the past given indications that rate rises would precede any asset sales. According to Governor Carney back in 2013, the first move would be to tighten conventional monetary policy, for some time, or to some degree, before considering adjustments to the size of the balance sheet.

Overall, in the context of the ongoing global economic recovery, the major central banks can adjust the parameters of their policy stance at a rather small cost in terms of market disruption/dislocation. As markets anticipate the first tightening steps from the major central banks, a channel that is likely to show some volatility is the exchange rate channel. This adds to uncertainty, as -among other things- it has implications for the medium-term outlook for price stability. In addition, a possible overshooting in the foreign exchange market could lead to fluctuations in the trade imbalances, including those of the euro area. The outcome of the normalisation process is likely to be determined by the interplay and the relative stance of the policies of major central banks as they move towards a less accommodative stance in the coming years, as well as by several structural features of the different economies. In any case, appropriate communication is vital to limiting any possible disruptions in the markets.

Part II: The benefits for Greece from the accommodative monetary policy

In Greece, the transmission mechanism had become fragmented and the accommodative monetary policy was not being transmitted fully. In part, the transmission problems reflected the significant liquidity squeeze that Greek banks experienced as they lost access to international markets and found the value of their collateral falling, as yields on Greek government bonds rose and collateral rules were tightened on a number of occasions. Furthermore, given the specific circumstances prevailing in the Greek economy, Greek government bonds are not eligible for the the purchase programme of public sector securities (PSPP ). Purchases of Greek private sector assets that could, in principle, be eligible for the Covered Bonds, ABS and Corporate Sector purchase programmes have so far been close to zero due to constraints relating to the rating of the available assets.

Nonetheless, Greece benefited indirectly. Positive spillovers from the accommodative monetary policy have been at play, and have worked through various transmission channels:

- The signalling channel: forward guidance by the ECB to maintain low interest rates and purchase assets into the future has helped lower overall interest rates that influence the financing cost of businesses and households.

- The portfolio rebalancing channel: the sellers of sovereign bonds to the ECB may replace these bonds with other securities (for example debt of other sovereigns or bank / corporate debt) resulting in lower yields for a broader range of riskier assets not participating in the programme. This includes Greek assets, and is illustrated by the recent successful issuance of a Greek government bond as well as of bonds of several corporates.

- The confidence channel: the decisive and unprecedented interventions across markets by the ECB improved confidence in the sustainability of the euro area, leading to a steep decline of tail risks. By safeguarding the euro, the policies have provided an anchor of economic as well as social stability in Greece.

Specifically, Greece benefited from:

- Low interest rates and forward guidance have served the Greek banks and the Greek economy.

- Besides the regular monetary policy operations, Greek banks also participated in the TLTROs (targeted longer-term refinancing operations) incentivising banks to lend to the real economy. TLTROs also ensure the provision of liquidity at very low interest rates over long periods of time, thereby safeguarding the stability of the financial sector.

- Furthermore, Greek banks obtained liquidity through the ELA mechanism, thus preserving financial stability and avoiding disruptions of the transmission mechanism in times of stress.

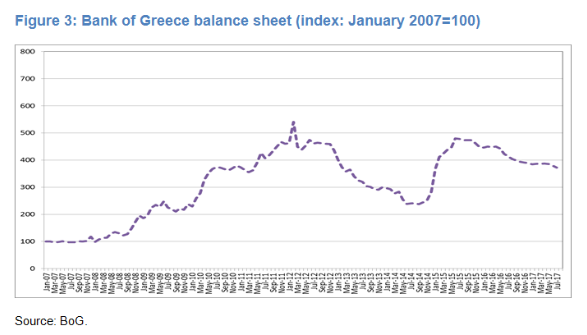

The aforementioned monetary policy measures were reflected in the evolution of the Bank of Greece balance sheet. Regular monetary policy and ELA refinancing and, more recently, its holdings of assets in the context of the EAPP (Expanded Asset Purchase Programme) have accounted for the bulk of the increase in the Bank of Greece balance sheet. It should be noted that the Bank of Greece purchases securities from supranational organisations in the context of the PSPP and securities of other euro area countries in the context of the CBPP3 according to its capital key. Based on the latest figures (August 2017), the securities held for monetary policy purposes by the Bank of Greece amount to around €55 bn. In July this year, the balance sheet was four times its pre-crisis level, after having grown almost fivefold in February 2012 and again in June 2015 following the two episodes of strong volatility in markets.

Part III: Recent economic developments in Greece and the potential impact of monetary policy normalisation

III.1 Greek economy: Recent developments and prospects

Confidence about Greece's economic prospects in general, and about the Greek banks in particular, has been gradually restored. This is reflected in the following:

- Successful return of the sovereign to the markets with the issuance of a new 5-year government bond.

- A sharp decline in the Greek government bond yields and their spread versus core countries' bonds, while the slope of the Greek Government Bonds yield curve turned positive and became steeper, implying improved investor perceptions for the outlook of the Greek economy - in line with the assessment of the rating agency Fitch which upgraded the rating of Greece - as well as a repricing of risks.

- Improvement in the liquidity conditions of Greek banks, as banks have improved their access to the interbank market, while deposits show signs of improvement. This is illustrated by banks' declining recourse to central bank funding (including to ELA) in the past two years.

- Improved bank profitability and comfortable capital adequacy ratios.

- Lower bank lending rates for firms, and slower deleveraging of banks' loan portfolios.

- Improved external financing conditions, as bank credit to non-financial corporations (NFCs) has stopped declining since early 2016 and market financing of NFCs has increased. These are positive signs that Greek companies are gradually getting access to market financing. This can substitute for part of the lack of bank credit and help finance investment.

The improved confidence in the Greek economy and the banking system allowed for significant relaxations of the capital controls in place since June 2015, and is evident in the increase of private deposits by about € 6 billion since then.

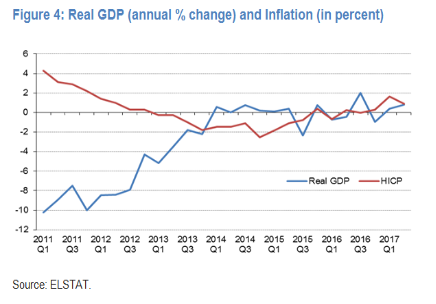

Following a prolonged period of recession, the Greek economy has once again a real chance to embark on a new growth path (see Figure 4). After the headwinds at the end of 2016 due to delays in the implementation of the adjustment programme, the economy moved into expansionary territory in the first two quarters of 2017, with real GDP growth amounting to 0.4% y-o-y and 0.8% y-o-y, respectively.

The completion of the second review in June 2017 allowed the positive momentum to continue. Recent soft data indicate a rebound in confidence.

- Economic sentiment continued to increase in August (to 99) on the back of an improvement in consumer confidence which reached a two-year high, as well as in business expectations in the services sector.

- The Manufacturing PMI has been in expansionary territory in the last three months, remaining above the threshold of 50; notably, in August the PMI reached an 8-year high (52.2), signalling strong growth in the Greek manufacturing sector.

Following these developments, it is expected that for the whole of 2017 GDP will rise by around 1.7%. The prospects for 2018 and 2019 are also positive, with GDP growth being projected at 2.4% and 2.7%, respectively.

On the employment side, over the past three years the private sector has been creating on average more than 100,000 new jobs per year, while the employment sub-index of the PMI in August suggested a record increase in employment (the highest since May 2002). However, the unemployment rate, although on a declining trend, still remains very high (June 2017: 21.1%). Turning to prices, deflationary pressures were contained in 2016, while in the first seven months of 2017 prices recorded a mild increase. Over the period 2017 to 2019, inflation is expected to be around 1%.

The abovementioned outlook is subject to both downside and upside risks:

- Some downside risks to the economic outlook relate to delays in the conclusion of the third review of the adjustment programme, the impact of increased taxation on economic activity and reform implementation, and the effect from global geopolitical uncertainty.

- On the other hand, upside risks are related to a quick completion of the third review, the further and sustainable access to international markets and the final exit from the programme in a year's time.

Finally, the debt relief measures to ensure sustainability of public debt must be specified as soon as possible, eliminating possible new sources of uncertainty. This would facilitate access to international financial markets in a sustainable way and would help towards abolishing capital controls and returning to financial normalcy. Postponing the decision on debt relief further down the road does not serve the purpose of a sustainable comeback to financial markets and a sustainable recovery of the Greek economy.

III.2 Potential impact of monetary policy normalisation on the Greek economy

The continuation of the highly accommodative monetary policy stance in the euro area fosters an economic environment conducive to growth.

However, given that the channels through which the non-standard measures were transmitted to Greece were either indirect or related to sentiment, the impact of normalisation can be expected to be smaller in Greece than that in other countries of the euro area. Indeed, financial conditions have recently been improving in Greece, as government bond yields have fallen, banks and non-financial companies have regained market access, and deleveraging has slowed. A tightening of the monetary stance of the ECB is unlikely to stand in the way of continued improvements in financial conditions.

Moreover, the Greek economy has already entered a phase of accelerating growth, and this should also help limit the detrimental effects of normalisation.

One possible channel through which normalisation might affect growth is via exchange rate fluctuations exerting a negative impact on exports.

- The effect of exchange rate fluctuations cannot be quantified at this stage. The extent to which we are likely to see a strong appreciation of the euro will depend on the pace of normalisation in the euro area relative to the pace of normalisation in other countries. The fact that around half of Greek exports are to non-euro area countries does imply that the exchange rate matters.

- However, the potential negative impact will be mitigated by the positive dynamics that have developed over the past years, as bold reforms in the labour and product markets helped to restore competitiveness, supporting the share of exports in GDP, and the rebalancing of the economy towards tradable, export-oriented sectors.

Thank you very much for your attention.