Urjit R Patel: Agricultural debt waiver - efficacy and limitations

Opening remarks by Dr Urjit R Patel, Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, at the Seminar on "Agricultural Debt Waiver - Efficacy and Limitations", Mumbai, 31 August 2017.

The views expressed in this speech are those of the speaker and not the view of the BIS.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

On behalf of the Reserve Bank of India, I warmly welcome you and thank you for accepting our invitation to join us today in this seminar.

1. In the recent period, farm loan waivers have engaged intense attention among the farming community, policy makers, academics, analysts and researchers. On the one hand, there is a gamut of issues that have intensified the anguish of our farmers. In this context, farm loan waivers have brought forward the urgency of designing lasting solutions to the structural malaise that affects Indian agriculture. On the other, there are concerns about the macroeconomic and financial implications, how long they will persist in impacting the economy, the possible distortions that they could confront public policies with, and the ultimate incidence of the financial burden.

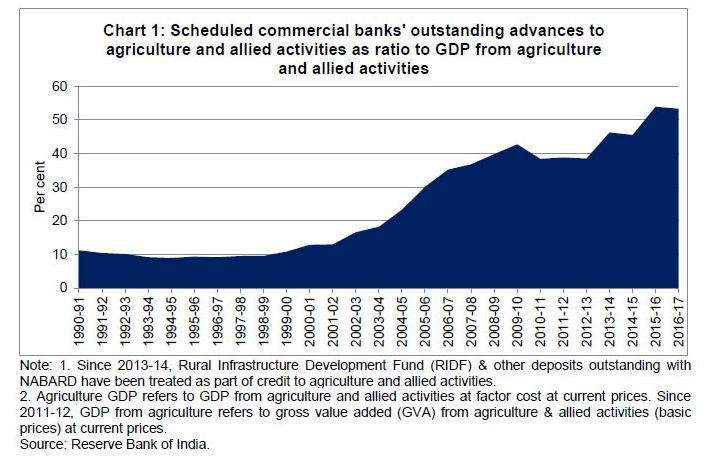

2. Let me, in a modest way, try to eclectically address both sides of the debate. India's agrarian economy is the source of around 15 percent of GDP, 11 per cent of our exports and provides livelihood to about half of India's population. The importance of the sector from a macroeconomic perspective is also reflected in a significant flow of bank credit to finance agricultural and allied activities relative to other sectors of the economy. Outstanding bank advances to agriculture and allied activities have risen from about 13 per cent of GDP originating in agriculture and allied activities in 2000-01 to around 53 per cent in 2016-17 (Chart 1). In real terms (adjusted for inflation measured by the GDP deflator), the growth of bank credit to agriculture and allied activities accelerated from 2.6 per cent in the 1990s to 15.4 per cent during 2000-01 to 2016-17.

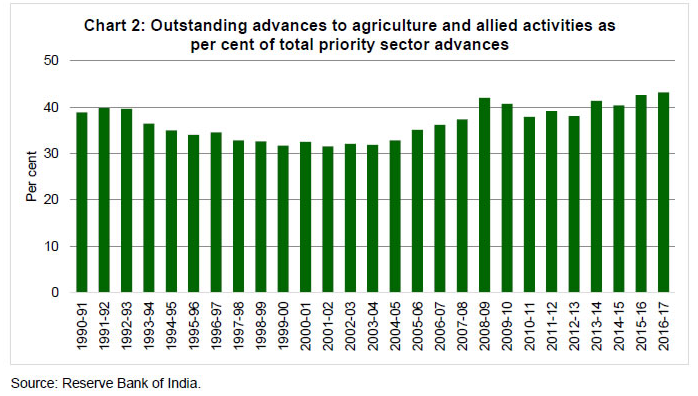

3. Much of this credit flow has been propelled by the policy thrust on expanding credit to agriculture, especially through priority sector lending (PSL) stipulations. Public sector banks and private banks are required to lend 18 per cent of annual net bank credit (ANBC) or credit equivalent amounts of off-balance sheet exposures, whichever is higher, to agriculture. Under this carve-out, 8 per cent is prescribed for small and marginal farmers. Even foreign banks with 20 branches and above have to achieve this target within a maximum period of five years starting from April 1, 2013 and ending on March 31, 2018. The share of outstanding advances to agriculture and allied activities in total priority sector advances has increased from 32.5 per cent in 2000-01 to 43.2 per cent in 2016-17 (Chart 2). Thus, without exaggeration, it is safe to say that financial flows to agriculture have been generous.

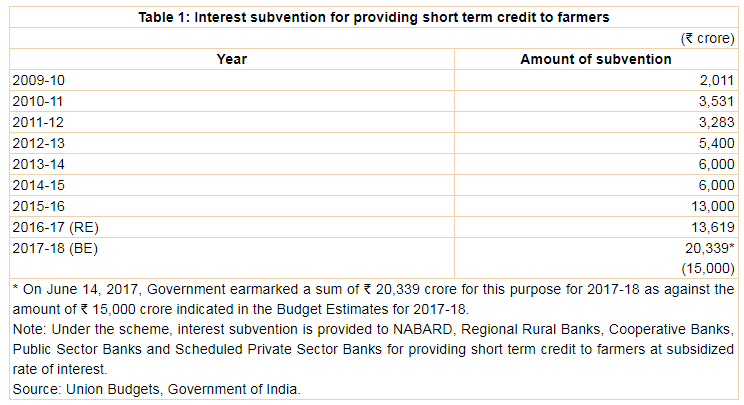

4. The Government has also undertaken several measures to compensate for the adverse terms of trade and the inert institutional architecture confronting agriculture in order to improve the profitability of crop production. The Interest Subvention Scheme has been running for a decade under which banks and cooperative institutions extend short term crop loans of up to ₹ 3 lakh to farmers at a concessional rate of 7 per cent. Timely repayment is incentivised by an additional subvention of 3 per cent. The scheme also encompasses other benefits, including post-harvest loans for storage in accredited warehouses against Negotiable Warehouse Receipts (NWRs) for upto six months for Kisan Credit Card (KCC) holding small and marginal farmers at a concessional rate of 7 per cent in order to avoid distress sales. During 2017-18, the Central Government will provide interest subvention of 5 per cent per annum to all prompt payee farmers for short term crop loans of up to one year. Many farmers will thus have to effectively pay only 4 per cent as interest on loans contracted from these institutions. In case farmers do not repay the crop loans in time, they would still be eligible for interest subvention of 2 per cent. On June 14, 2017 the Government earmarked a sum of ₹ 20,339 crore for this purpose for 2017-18 as against the provision of ₹ 15,000 crore originally made in the Union Budget (Table 1). During 2016-17, the volume of short term crop loan lent stood at ₹ 6,22,685 crore, surpassing the target of ₹ 6,15,000 crore.

6. Despite the sizeable volume of subsidised and directed credit flows as well as the various fiscal incentives, Indian agriculture is beset with deep seated distortions that render it vulnerable to high volatility. It has perennially been characterised by low investment, archaic irrigation practices, monsoon dependence, fragmentation of land holdings and low level of technology. Lack of property rights and low initial net worth of farmers add to the constraints. Consequently, considerable flux in output and prices is common, imposing large losses on farmers and potentially imprisoning them in a circle of indebtedness with disturbing frequency. Therefore, in the absence of coordinated and sustained efforts to put in place elements of a virtuous cycle of upliftment, loan waivers have periodically emerged as a quick fix to ease farmers' distress.5. Earlier, the Union Budget 2014-15 had put in place a scheme under which five lakh Joint Liability Groups of 'Bhoomi Heen Kisan' (landless farmers) will be financed through the NABARD in order to augment flow of credit to landless farmers cultivating land as tenant farmers, oral lessees or share croppers and small/marginal farmers as well as other poor individuals taking up farm activities, off-farm activities and non-farm activities. The experience of catalysing bank credit flows to agriculture and expanding the panoply of subventions begs the question: Are we substituting credit for other policy interventions? Indeed, this issue prompted, in 2014, RBI's Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework to recommend a revisit of the need for subventions on interest rates for lending to agriculture.

7. A brief history of farm loan waivers in India may be in order. The first major nationwide farm loan waiver was undertaken in 1990 and the cost to the national exchequer was around ₹ 10,000 crores, which works out to ₹ 50,557 crores at current prices using the GDP deflator. The second major waiver was under the agricultural debt waiver and debt relief scheme (ADWD) of 2008 amounting to ₹ 52,000 crores (0.9 per cent of GDP) or ₹ 81,264 crores at current prices using the GDP deflator. Unlike the 1990 scheme that aimed at providing blanket relief to all farmers up to a certain loan amount, the 2008 scheme waived debt for certain classes of cultivators1. In 2014, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana announced farm loan waiver of ₹ 24,000 crores and ₹ 17,000 crores, respectively. Beginning with Tamil Nadu in 2016, domino effects have spread in 2017 to several states and the total cost of loan waivers announced amounts to around ₹ 1,30,000 crores (0.8 per cent of GDP). I am sure that the proceedings today will dwell upon the details characterising each scheme. Therefore, I will move on.

8. The pros and cons of agricultural debt relief have been widely debated and literature has evolved around the theme. Alongside beneficial effects in terms of clearing the debt overhang of farm households, negative side effects in the form of faulty targeting of beneficiaries and resulting discrimination, incentivising wilful defaulters, and erosion of credit discipline have been cited. I am pleased to note that several luminaries driving the evolution of these ideas are present here today. Rather than attempting an uninformed evaluation, I am personally looking forward to the guidance of experts present here on various issues that intermingle around the subject.

9. Let me now turn to the other side of debate - the implications for macroeconomic conditions and policies. The first impact of any loan waiver is on the balance sheet of lending institutions, be they formal or informal. This is inherent in the inevitable lags, in the timing of impact and the arrival of compensation from the government. In this interregnum, the quality of assets deteriorates and bridge provisions crowd out new loans. In the second round, loan waivers impact the state of public finances in the form of higher than budgeted revenue expenditure. This, in turn, has to be financed by additional market borrowings which pushes up interest rates, not just for the States but for the entire economy. A collateral damage is that private borrowers are crowded out of the finite pool of investible resources as the cost of borrowing rises. Even if the loan waiver is accommodated within budgetary provisions, it will force cutbacks in other heads of expenditure. Experience has shown that the most vulnerable category is capital expenditure. In turn, this will entail deterioration in the quality of expenditure and inter alia lead to adverse implications for productivity as asset forming investment, including for the sector itself - e.g., irrigation works, cold storage chains etc., - is foregone. If capital/infrastructural constraints are binding, a reduction in capital expenditure for the sector that would have benefitted from this expenditure could even be inflationary as costs - including time value/opportunity cost of delays and material damages - go up as a result of capacity constraints becoming even more acute and attendant "congestion charges". If, on the other hand, budgetary provisions are exceeded, higher spending and widening of the fiscal deficit have, as experience has shown, inflationary consequences, and possible spillovers that could undermine external viability (the twin deficit argument). Also, research points to adverse welfare effects because, ultimately, loan waivers involve a transfer of resources from tax payers to borrowers. Consumption redistribution effects have also been reported.

10. As you would have noted from these initial remarks, farm loan waivers have stirred up considerable passion and polarised opinions. While in no way detracting from the acute distress that farmers face with every disruption in crop cycles, it is important to recognise that there are externalities that spill over beyond the farm sector. Eventually, other economic agents and other parts of the economy get affected. How can these spill overs be minimised? How do we defray the incidence of the burden on tax payers? From a policy perspective, what needs to be done to move away from palliatives in the form of debt relief and into a more fundamental solution that enhances welfare all around? Many elements of this optimal approach are well known - crop insurance, infrastructure, irrigation, technology-enabled productivity improvements, and, opening up the farm economy to market forces and open trade. The Government's initiative to establish a nation-wide market for agricultural produce, through eNAM, the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana, the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana and the national drive towards financial inclusion for all are important initiatives in this direction. The coming to fruition of these initiatives holds the potential of achieving the mission of doubling farmers' income over time. We need to ensure that their benefits percolate down to all the intended recipients.

11. I will refrain from either prejudging or influencing the rich discussions that are expected to occupy your minds during the rest of the day. I am sure that amidst the heat and dust, this seminar will shine light on the multi-faceted discourse on farm loan waivers. So I will stop here and wish you all success in your deliberations.

1 The 2008 scheme waived debt by classes of cultivators whereby small and marginal farmers (that is, farmers holding up to one to two hectares of land) received a full waiver of all loans overdue, while other farmers were given a one-time settlement - rebate of 25 per cent against the payment of the balance 75 per cent.