François Villeroy de Galhau: The future of the finance industry - between austerity and innovation

Speech by Mr François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Bank of France, at the Süddeutsche Zeitung Finance Day 2017, Frankfurt am Main, 22 March 2017.

The views expressed in this speech are those of the speaker and not the view of the BIS.

I am grateful to Marine Dujardin and Banque de France and ACPR staff for their assistance in preparing these remarks.

It is a great pleasure to be with you today and I'd like to thank you sincerely for inviting me.

I am here in Frankfurt as a committed European and as a friend of Germany; and not just because I travel here at least once a fortnight for the meetings of the ECB Governing Council! On a more personal level, I am French but my roots are in Saarland. My family has lived there since the end of the 18th century and its porcelain manufacturing company Villeroy & Boch is part of the German "Mittelstand".

But today, to discuss the future of the finance industry, I'm going to be talking in my capacity as a member of the Governing Council and President of the French supervisory authority (the ACPR, which I'm sure some of you know). First I would first to say a few words on the Eurosystem's monetary policy and our latest decisions. Then I'll share with you my thoughts on how to respond to the current challenges facing the finance industry. This is not a side issue for central bankers, as we are now in charge of financial stability as well as price stability. Moreover, a robust and profitable financial sector is one of the prerequisites for the proper transmission of our monetary policy.

1. Where do we stand in the euro area with respect to monetary policy?

I am fully aware of the heated debate here in Germany surrounding our monetary policy.

A debate that is fully legitimate, but let us try to keep it rational, and avoid getting emotional. "Mehr Licht!" (more light!) if you allow me to quote Goethe's last words. This is exactly what I would like to do today: to shed light on our reasons and our progress.

As you know, the ECB was shaped according to the model of the Bundesbank, and I do believe that the Eurosystem's collective monetary policy is very much aligned with the German values that I fully share and admire: independence, respect of the Treaties, price stability and a long-term approach. As price stability is the mission entrusted to us by the European Treaties, we have a duty to make it our primary focus. Price stability means an inflation rate of close to, but below, 2% over the medium-term. This has been our definition since 2003, and it is a definition that most central banks in developed countries share - what Jean-Claude Trichet rightly terms as "a great convergence". So our inflation targeting in the euro area is nothing new or specific; and our present monetary policy is not some uncontrolled Latin flight of fancy.

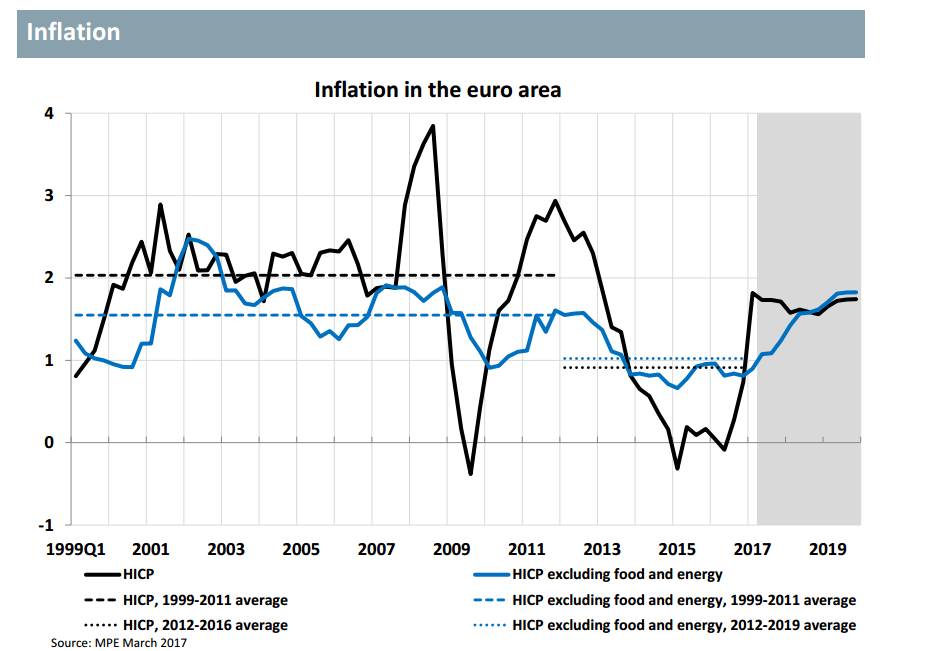

In practice, the euro area experienced a remarkable period of price stability up until the crisis. But as of 2013, inflation dropped well below the 2% mark. Our mandate meant we had to react in order to bring inflation back to healthier levels for our economies. And we are clearly progressing towards our objectives. Our monetary policy works; the measures we have put in place since 2014 have already been successful.

First, [slide 2] we have warded off the mortal danger of deflation, and inflation is gradually recovering in the euro area. Headline inflation peaked at 2% last month, up from -0.2% in April 2016. The sharp - and partly temporary - uptick at the beginning of this year is mainly due to the rebound in energy and food prices, as underlying inflation remains below 1% (and 1.2% in Germany). However underlying inflation is expected to rise gradually to 1.8% in 2019. We are reasonably confident that both headline and underlying inflation will converge, close to our target in 2019; and this convergence, which is not often stressed, is a key element in our forecasts, as it is crucial to the mid-term sustainability of the inflation path.

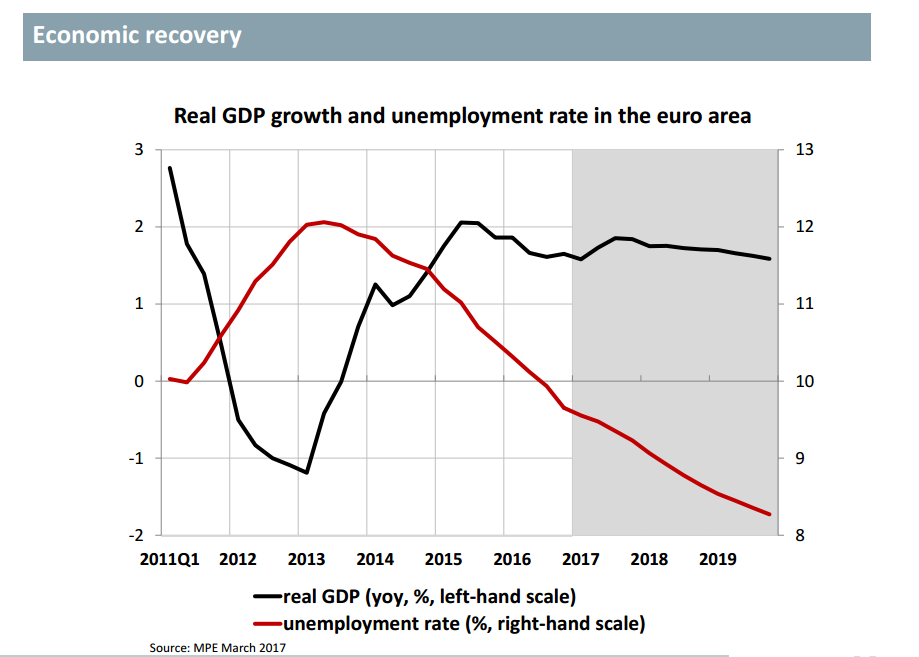

Second, our accommodative monetary policy has ensured very favourable financial conditions: lending to firms and households has continued to grow in the euro area, although at a reasonable pace - +2.3% for firms and +2.2% for households in January 2017 - and borrowing costs have significantly declined. Third, [slide 3] the economic recovery is firming and broadening. Fortunately, this appears to be a worldwide trend: our G20 communiqué

in Baden-Baden last week started with the words "We met at a time when the global economic recovery is progressing", while also stressing that significant risks and uncertainties remain. Euro area monetary policy has played its part in this recovery, and the latest ECB staff projections foresee higher GDP growth for the region, at 1.8% in 2017. The euro area unemployment rate dropped to 9.6% in January of this year, its lowest level since 2009. And the recovery is also broadening across euro area countries, including in France: despite some temporary political uncertainty generated by the upcoming elections, France's economic outlook is improving. The country has also not been inactive over the past few years when it comes to reforms: pensions have been reformed, corporate charges have been cut considerably, and labour laws have been made more flexible. Like you, I would like France to pick up the pace of reform; I say it frequently in my own country. But you shall not regard your French neighbour as "unreformable". These reforms are crucial, as monetary policy can obviously not be the only game in town, and less and less so as we progressively close the output gap.

Now, the question that comes to mind, especially here in Germany, is: given this progress, should we stop pursuing an accommodative monetary policy? At this stage, the answer is clearly no. Without monetary stimulus, the recovery in inflation would not yet be self-sustained or durable throughout the euro area. That is why we are maintaining an accommodative stance while adapting its intensity. Regarding this intensity, we decided to cut our monthly asset purchases by €20bn - from €80bn to €60bn - starting next month.

We did not deem it necessary to launch a new series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) after the last one today. And we - including Mario Draghi and myself - clearly stressed the limits of negative interest rates.

Let me add the following: I often read comments describing our debate within the Governing Council as a "predetermined" one, between the hawks on one side and the doves on the other. I don't think this is accurate: in all our monetary policy decisions, what I believe matters is to take a pragmatic approach, based on a thorough assessment of the present economic environment in the euro area and of the specific structure of its financing channels.

This is why our forward guidance now is this one, based on our current information. But what we clearly did is to give the financial and economic sectors visibility over our monthly purchase volume for the whole of 2017.

2. What are the challenges facing the finance industry and how should we tackle them?

A healthy financial sector is key for a robust economic recovery. I'd like to remind you of the significant progress that has been made in this area since the financial crisis. We shouldn't judge the European financial sector only on the basis of its difficult cases, or those "trailing at the rear". On average, the sector is now far more resilient than before the crisis. This is the result of considerable work carried out to strengthen regulation and to harmonise supervision in the euro area, notably with the Banking Union which is a significant step forward. It also comes from the industry's remarkable efforts: European banks are now in a much stronger position than a decade ago, in terms of capital, liquidity or risk-taking. Regarding their capital for instance, the Common Equity Tier 1 ratio of significant euro area banking groups has risen from less than 7% in 2008 to more than 14% today. Overall, banks are now less risky, and investors should take into account this progress by reducing their expected rates of return: banks' cost of equity should go down.

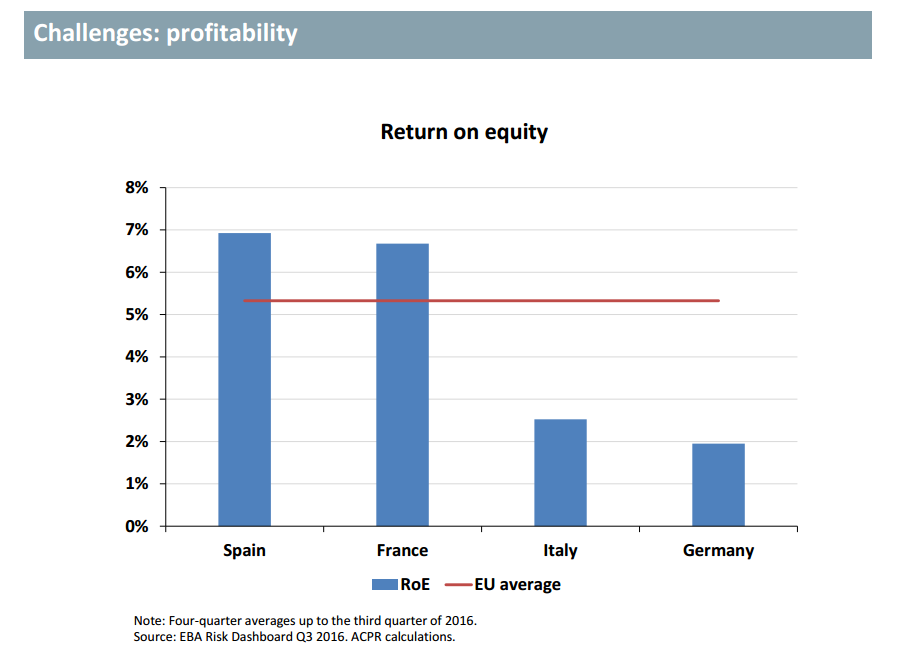

However, while solvency has improved, there is still one challenge facing European banks: profitability [slide 4]. The average return on equity varies significantly across countries - and France ranks among those with the most solid in the euro area - but on average it has stagnated at around 5%. This situation raises three questions, about three possible factors: low rates, non-performing loans and the digital transformation.

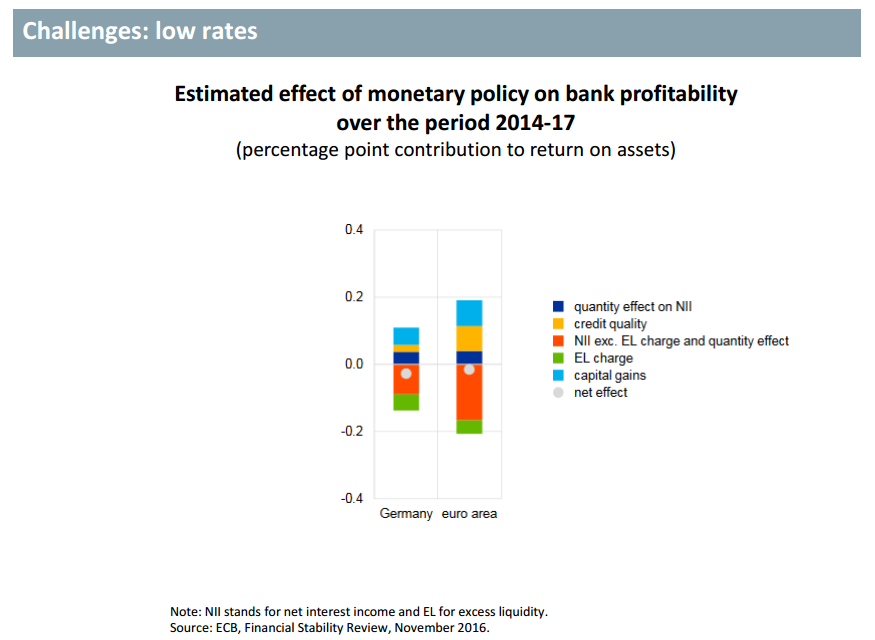

The first factor, and the one most frequently mentioned, although sometimes to excess, is the low interest rate environment. Insurers and pension funds with a high level of fixed rate guarantees may suffer. As for banks, their net margins have been squeezed by the low interest rates and the flattening of the yield curve. However this question needs to be examined from all angles [slide 5]. Monetary policy has also had offsetting effects: lending volumes have picked up again; banks have booked significant capital gains; the cost of risk has fallen as borrower solvency has improved; the cost of funding including market and ECB financing has become cheaper. All in all, the overall impact of our non-standard monetary policy measures on bank profitability is expected to be modest for the period 2014-17. Furthermore, nominal interest rates are slightly on the rise since the turning point in August 2016, and nominal rates are the ones - not real ones - which matter for bank profitability, as well as the slope of the yield curve.

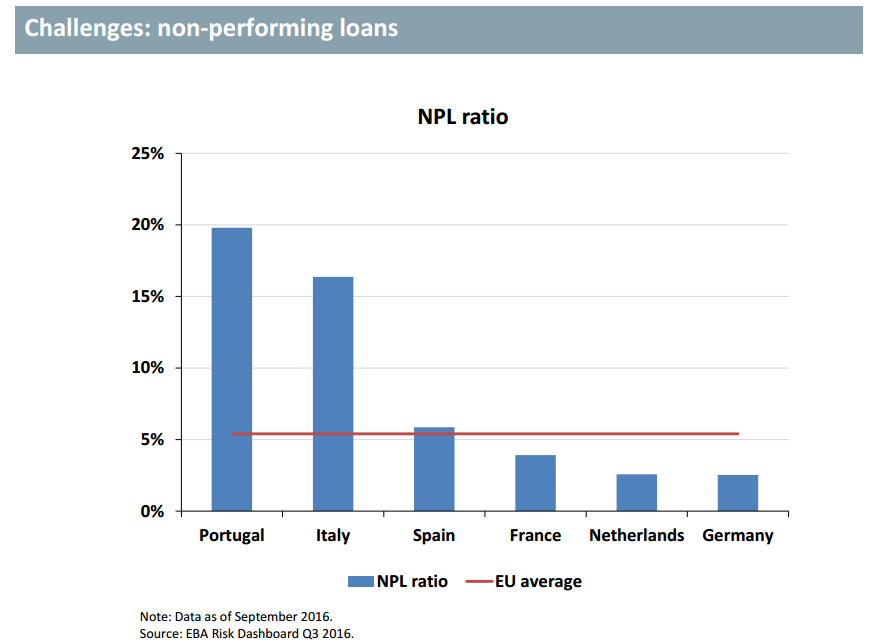

The second factor putting pressure on profitability is the level of non-performing loans [slide 6]. This is not a widespread issue: the average NPL ratio is 5.4% in the European Union as of September 2016, and in many countries, including France and Germany, it is below 4%. But it is a challenge which seriously affects specific banks in certain countries, mainly Italy and Portugal. So this challenge is manageable, but it needs to be actually managed: the quicker the better. Recent initiatives by Italian authorities are a step in the right direction, with the active involvement of European supervisory authorities.

Third factor: the digital transformation. It is true that digitalisation is disrupting traditional customer relationship models. But it also creates opportunities: for instance, more diverse and accessible financial services, more complete customer satisfaction, greater valorisation of data. Yet, in order to succeed in the digital transition, financial companies need first to place innovation at the heart of their strategic management; and second to examine ways of transforming their business models, mainly in Retail. Obviously these are difficult choices that need to be made by the companies themselves. The strategic way forward is not up to regulators, and will not be uniform. That said, let me share some thoughts with you.

On the income side, the response could be twofold: diversifying the range of services - both proprietary and via partnerships - that are offered to customers; and adjusting existing pricing policies, with fewer flat-rate prices and more pricing by use. On the costs side, the digital transition involves preparing for shifts in jobs and in skills, through enhanced dialogue with social partners. Moreover, it calls for major IT investment aimed at providing services that remain aligned with customer needs, reducing structural costs and improving regulatory compliance. IT systems will need to be - and this is far from simple - more secure so that they provide strong protection against cyber-risks, but at the same time more flexible and open to interconnectivity.

Our duty as regulators in this revolution is obviously not to discourage innovation, but to ensure a level playing field with FinTechs - taking into account their lifecycle according to a "proportionality principle" - and still more tomorrow with bigger data platforms, be they GAFAs or their equivalents. This level playing field will have to apply for capital or liquidity requirements, for prudential supervision as well as for data protection: if you play the same game, you have to obey the same rules.

In addition to adjustments to business models, cross-border bank consolidations in the euro area would also help tackle this efficiency issue. The Banking Union provides both the justification and the framework for such a financial integration - we still lag far behind the American market in this respect. Cross-border consolidations on a sound and safe basis would make banks better able to diversify their risks across the euro area, and channel savings more effectively towards investments across borders.

As regulators, we obviously have a part to play in helping the finance industry adapt.

We should strive to reduce uncertainties as much as possible.

One source of uncertainty today is the regulatory framework. Nearly ten years after the crisis, our priority must be to stabilise the rules. The main elements of the Basel III package have already been approved in 2010-11 and have largely entered into force. But there are still ongoing discussions regarding the measurement of risk on bank balance sheets. The objective, as you know, is to reduce the unwarranted variability of results between banks and across jurisdictions. And as the German G20 reiterated last week, the completion of reforms must not result in a "significant increase in overall capital requirements". We have not yet reached an agreement. Thanks to our mobilisation and that of our European partners, we have avoided a bad agreement. For the coming months then, our objective is to reach a good one.

Another source of uncertainty is Brexit. With article 50 about to be triggered, we obviously cannot prejudge the outcome of the future negotiations. But it is essential to bear one principle in mind: in the single market, you cannot separate access and rules. In financial services in particular, you can hardly expect to have a European passport if you don't accept the single market's rules. Let us be clear: we are saddened by Brexit, and we are not the ones who have decided to have a so-called "clean Brexit". But if this is the case, then there can be no cherry-picking, no "Europe a la carte", no "Rosinenpickerei".

It has been nearly ten years since the global financial and economic crisis. We have come sa long way, but there are still challenges ahead of us for the ten years to come. Yet the challenges for the financial industry are gradually changing in nature: they could shift from adapting to the regulatory or monetary policy environment to reflecting on new business model strategies. In this regard, the expected strengthening of the economic recovery will hopefully make the path smoother. Austerity - or rigour - will remain necessary, but innovation will be the game changer. Thank you for your attention.

Slide 2

Slide 3

Slide 4

Slide 5

Slide 6