P2P lending in China

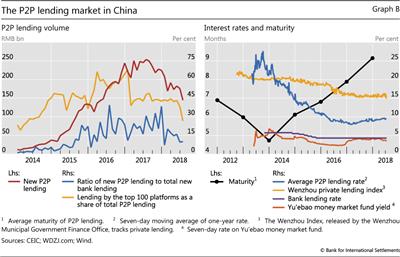

P2P lending has become a significant source of funds for small firms and consumers in China. The ratio of new P2P loans to new bank loans rose to almost 40% in June 2016, before falling to less than 10% in June 2018 (Graph B, left-hand panel). As P2P loans mainly meet borrowers' short-term funding needs, maturities are rather short (right-hand panel); the ratio of outstanding P2P loans to bank loans was only about 1% in June 2018. Market concentration is low and falling: the top 100 platforms' share was below 30% in July 2018 (left-hand panel).

Several unique factors have contributed to the more rapid rise of P2P lending in China. First is the relative availability of financial services: P2P lending caters to borrowers that formal credit intermediaries typically ignore, especially small and micro firms and consumers on whom the creditworthiness information is at best imperfect. P2P lending rates, though higher than those of banks, are far lower than the private lending rates available for such borrowers (Graph B, right-hand panel). Limited alternative investment opportunities and the promise of higher returns have also attracted many retail investors. Second, Chinese consumers, merchants and investors have enthusiastically embraced mobile technology for financial transactions, including payments (Ernst and Young (2017)). Third, an initially more permissive regulatory environment encouraged firms to innovate and expand, with a growing number of platforms supported by the state and venture capital. In recent years, however, the regulatory regime has tightened.

The modalities and risks in the Chinese P2P lending market have changed over time. In the early period following its inception in 2007, P2P credit firms in China operated simple matching models, whereby investors bid for contracts offered by borrowers. From around 2012 onwards, platforms moved to more complex structures where investor funds were pooled (Shen and Li (2018)). Many platforms provided guarantees on loan principal and interest, and promised "rigid redemptions". But risks rose due to inappropriate market practices and fraud, including Ponzi schemes. Defaults surged and the number of problem platforms reached 114 in June 2015. Over the next two years, authorities implemented a nationwide "clean-up" that aimed to ensure internet finance firms acted as information rather than as credit intermediaries. New rules prohibited existing practices by P2P firms such as raising funds for themselves or guaranteeing investments, and mandated the depositing of client funds. Further specific measures were taken in 2017: new student loans were banned and the regulation for cash loans was tightened. The industry has consolidated significantly, with many problem platforms exiting the market (Graph 5, right-hand panel). Yet this process is still incomplete; risks remain and the number of problem and failed platforms has risen sharply in recent months.