Innovation

Innovation has always been part of the BIS's DNA. In a world of change, it is only through innovation that the BIS can remain useful and relevant to the global central bank community. Throughout the Bank's history, innovation has taken many forms.

1930s

Meeting of central bank Governors and experts at the Hôtel Stéphanie in Baden-Baden, Germany, to draft the statutes and charter of the Bank for International Settlements, October-November 1929.

1950s – 1960s

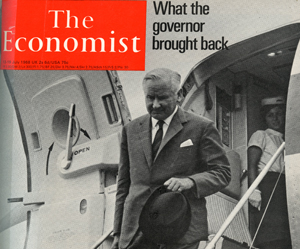

Cover page of -The Economist- in 1968. Bank of England Governor O'Brien, returning from a BIS meeting in Basel in which he had secured central bank support for sterling.

1988 – 1996

Opening ceremony of the BIS's Representative Office for Asia and the Pacific in Hong Kong SAR, 1998.

1977 – 2007

Meeting of the BIS Board of Directors in September 1994. It was the first board meeting in which the Governors of the central banks of Canada, Japan and the United States all participated.

2009 – 2022

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) and the BIS sign the Operational Agreement on the BIS Innovation Hub Centre in Switzerland, 31 October 2019.