Climate risks: scenario analysis – Executive Summary

Scenario analysis is a key tool to assess financial risks arising from climate change, as standard risk modelling cannot adequately capture the unprecedented nature of climate risks1 and the inherent uncertainty of future climate-related events. To help central banks and supervisors, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) published a guide on how to use scenario analysis to assess climate risk impacts. It has also published reference scenarios that are increasingly used by public and private sector players to analyse climate-related financial risks.

Scenario analysis – a four-step process

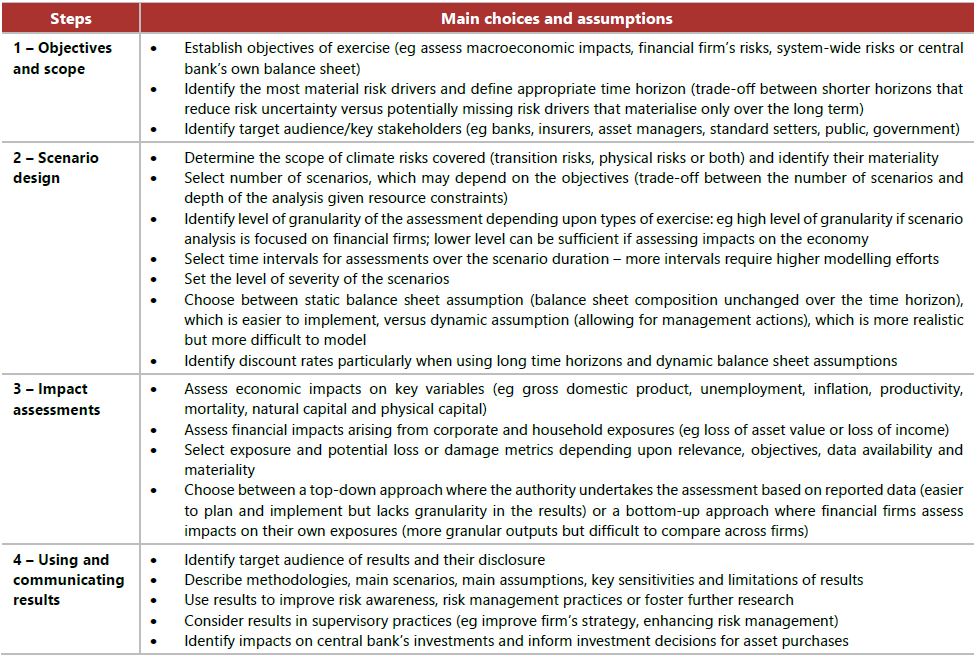

The first step is to decide on the objectives and scope of the exercise. The second is to select and design the scenarios. The third step involves assessing economic and financial impacts. The fourth step relates to using and communicating the results. The main design choices and assumptions are summarised below.

Table: Scenario analysis process – main choices and assumptions

NGFS reference climate scenarios

The reference climate scenarios of the NGFS provide a starting point to explore economic impacts and financial risks arising from climate change.2 Each scenario explores a different set of assumptions about how climate policy, emissions and temperatures evolve. Scenarios are characterised by their overall levels of physical and transition risks. These levels are based on assumptions relating to policy ambition, timing, coordination and technological developments. The NGFS scenarios fall into three categories: orderly, disorderly and "hot house world". Each category consists of two scenarios reflecting different levels of physical and transition risks. The categories and scenarios are as follows:

- Orderly scenarios assume that climate policies are introduced early and become gradually more stringent, allowing physical and transition risks to be subdued. The two scenarios are Net Zero 2050, where global warming is limited to 1.5° Celsius (C) by that date through stringent climate policies, reaching net zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions around 2050, and Below 2°C, where gradually more stringent policies provide a 67% chance of limiting global warming to below 2°C.

- Disorderly scenarios explore higher levels of transition risks due to policies being delayed or divergent across countries and sectors. The two reference scenarios are Divergent Net Zero, in which net zero is achieved around 2050 but with higher costs due to divergent policies introduced across sectors to phase out fossil fuels, and Delayed Transition, where annual emissions are assumed not to decrease before 2030 and, therefore, harsher policies are needed after 2030 to limit global warming to below 2°C.

- Hot house world scenarios assume that global efforts are insufficient to halt global warming and lead to the most adverse economic impacts in the long run. These scenarios result in severe physical risks, including irreversible impacts like sea level rises, but low transition risk. The reference scenarios are Current Policies, the most adverse of all, where only implemented policies are considered and median temperatures reach 4°C by 2100, and Nationally Determined Contributions, which considers all pledged targets even if not yet supported by implemented policies. Physical risks would be lower than under Current Policies but median temperatures would exceed 3°C by 2100.

Common challenges

When undertaking climate scenario analysis, some of the challenges include:

- difficulties in translating scenarios into shocks to a specific economy, sector, financial firm or financial instrument and in identifying and sizing the multiple transmission channels, the ways firms respond to climate shocks and the extent to which costs can be passed on to customers.

- identifying climate risk-sensitive sectors and difficulties in disaggregating the overall impact of NGFS scenarios on the economy and attributing it to specific sectors

- data-related issues, such as a lack of granular counterparty-level emissions data and lack of consistent and comparable reported data by non-financial firms.

This Executive Summary and related tutorials are also available in FSI Connect, the online learning tool of the Bank for International Settlements.

1 Climate risks include physical risks and transition risks. Acute physical risks result from the increasing frequency and severity of extreme climate or weather events (such as heat waves or floods). Chronic physical risks arise from long-term shifts in climate and weather patterns (such as rising average temperatures). Transition risks are financial risks that result from moving to a low-carbon economy. They are driven by changes in policies, technology, market sentiment or customer behaviours.

2 The NGFS scenarios are updated annually. In their third vintage, the scenarios were updated with new economic and climate data and policy commitments. In the fourth vintage for 2023, the NGFS aims to improve scenario design by increasing sectoral granularity and geographical coverage, introducing a short-term scenario, better representing physical risks and updating the underlying data and models.