John Iannis Mourmouras: Post-Brexit effects on global monetary policy and capital markets

Speech by Professor John Iannis Mourmouras, Deputy Governor of the Bank of Greece, at an event organised by the Hellenic American Association for Professionals in Finance (HABA), New York City, 5 October 2016.

The views expressed in this speech are those of the speaker and not the view of the BIS.

Views expressed in this speech are personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions I am affiliated with.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to be here. I would like to thank the Directors and the new President of HABA, Fanny Trataros, for the kind invitation and also Bob Savage for his welcoming remarks. Fanny, please allow me here to wish you all the best with your work for the Greek-American financial community.

In the early days following the UK vote to leave the EU, most people were very apprehensive, even fearful, I dare say, about what the future would bring. Once again the end of the world has not come- yet. I decided to speak today about the implications of this seminal decision by the British people for themselves, but also for the rest of continental Europe, offering a more sanguine and all-around view. No matter if it is a light or full-blown Brexit, the surrounding uncertainty impacts political sentiment in other EU Member States and heightens pressure to adopt inward-looking policies. As a result, the future European and global economic and financial outlook remains inconclusive.

My lecture will be structured around the following three questions. Firstly, a little bit of finance and, more specifically, which are the future post-Brexit prospects of global capital markets. I couldn't avoid this question given the audience's involvement in the financial industry. My second question is about monetary policy and, in particular, about the implications of the Brexit vote for what central banks do, including the ECB. The third question regards the dynamics of European integration following the Brexit vote, offering a Southern point of view on the subject.

1. The post-Brexit prospects of global capital markets

It is true that financial markets have weathered the spike in uncertainty in the aftermath of the Brexit vote surprisingly well, while the IMF has downgraded from high to medium the risk for Brexit's repercussions on the UK itself, the EU and the global economy. However, for market analysts, private investors and the official sector, the question remains pending: has the tail risk scenario really diminished? First, allow me to make two-three general remarks on the global financial markets' latest developments before giving you my own insights on the prospects by year-end for the so-called G4 (US, UK, eurozone and Japan) major currencies, as well as equity and bond markets.

· General remarks

1. Heightened policy uncertainty

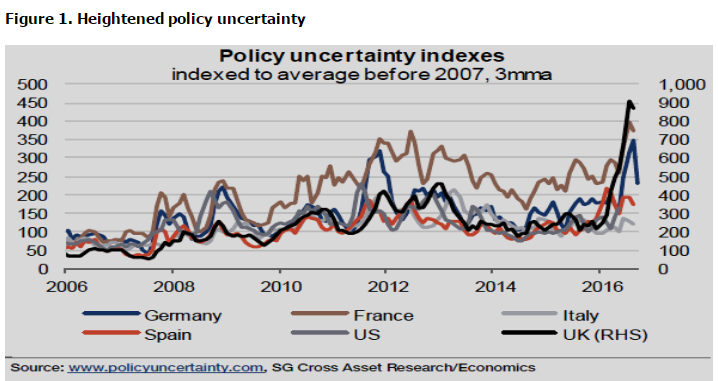

While the market outlook stabilises, political risks take center stage, as there is almost one month left (only 32 days) until November election day. After Brexit any ballot can bring disorder. Looking ahead, we will see a busy electoral agenda on both sides of the Atlantic. First is the US presidential election, it follows the Italian referendum on constitutional reform in early December, and in 2017 there are elections in the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, France and Germany. Italy is set to follow in early 2018. Given rising populism, there is a non-negligible risk that one of these events might produce a political "accident". Moreover, the prevailing uncertainty is likely already to be acting as a headwind (Figure 1). Brexit, however, offers an interesting lesson. Rather than the dramatic event of imminent recession and financial turmoil feared, it looks set to be a prolonged, slow process driving structurally weaker growth.

2. Volatility remains low in fragile global markets

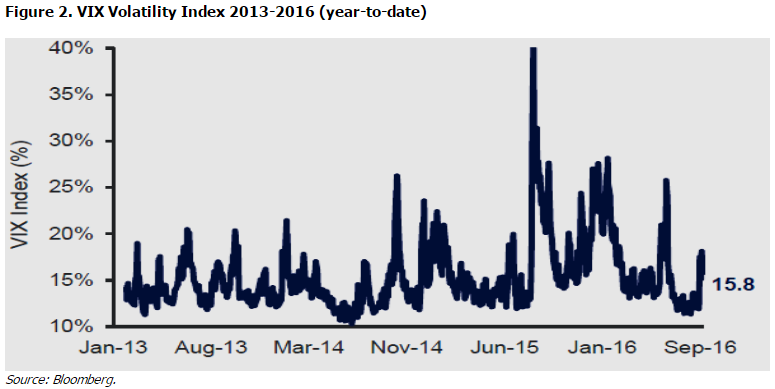

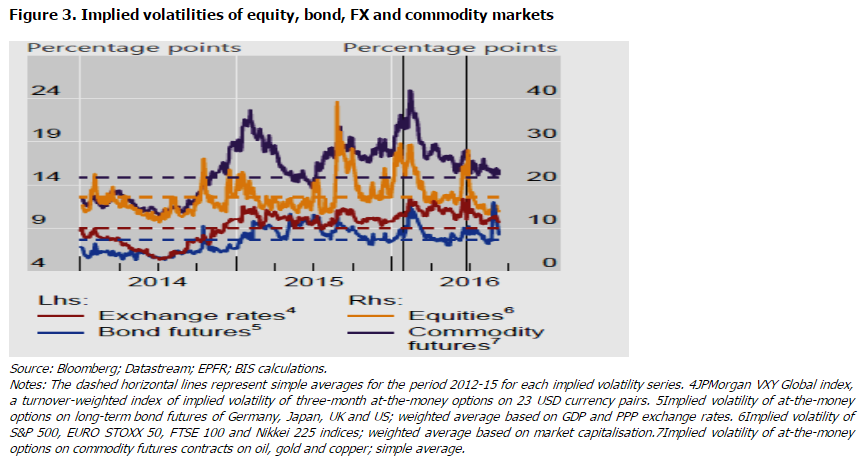

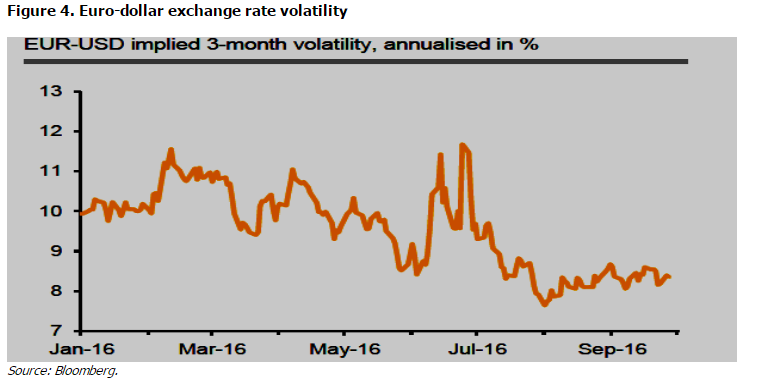

Following the Brexit vote, implied volatilities followed a downward trend towards or below levels recorded at the start of the year. Stock market volatility quickly approached the lows last seen in July 2014 and FX implied volatility is trading today near historic lows. Volatilities in other markets were less subdued, fluctuating around their recent averages and are still far from their depths in 2014 (Figures 2, 3, 4).

Although, markets proved resilient to a number of potentially disruptive political developments, questions linger as to whether the configuration of asset prices accurately reflected the underlying risks. The apparent contrast between record low bond yields, on the one hand, and sharply higher stock prices with subdued volatility, on the other, cast a shadow over such valuations.

3. Global growth is continuing along at a slow pace

A range of indicators suggest that the euro area economy remained remarkably resilient after the vote. The negative impact of the UK's vote to leave the EU on growth, in the UK and the euro area appears to have been materially less than initially expected. ECB's President Draghi said recently that the effect of the Brexit vote on the eurozone's growth is estimated at around 0.5% over three years. Despite an array of negative domestic and external events over the past two years - the Ukraine crisis, the fear of a Grexit, China's currency volatility, banking sector volatility and the Brexit vote - the euro economy has sustained a remarkably steady pace of growth between 1.3% and 1.8%. Thus, the GDP growth for the euro area is estimated at 1.7% growth for this year, while for next year, the economy is seen slowing to a pace of 1.6%, as Brexit hampers investment and export flows in the region.

As far as the UK is concerned, resumed political stability, a weaker currency and the Bank of England's policy response look to have stabilised activity, after confidence fell sharply in the wake of the vote, and now the British economy is expected to exhibit significant resilience post-Brexit. That may be sufficient for GDP to avoid a modest contraction. According to the Bank of England's latest Inflation Report, GDP is forecast to remain unchanged to 2% in 2016, whereas the 2017 forecast was slashed to 0.8% from a previous estimate of 2.3%, i.e. a drop exceeding the one seen during the 2008 financial crisis! Correction in asset prices, a housing market downturn, or a large decline in consumption, represent downside risks to the UK's economy.

As regards other advanced economies, the 2016 growth forecast was marked slightly down to 1.6%, while the global growth is projected to slow to 3.1% in 2016 before recovering to 3.4% in 2017. One of the more problematic features of the current cycle is its over-reliance on consumers, while business investment and trade continue to disappoint.

· Foreign exchange markets

I turn to foreign exchange (FX) prospects by end-year.

The euro against the dollar

Political developments on both sides of the little pond seem to be the major driver of FX price developments (US Presidential elections, referendums-national elections in Europe). As a result, the dollar's strength is expected to be limited and the euro against the dollar to move in a tight range of 1.06-1.16 by year-end.

British pound

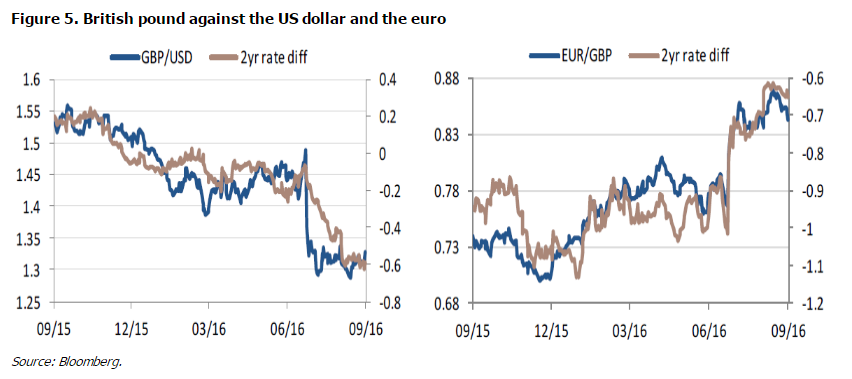

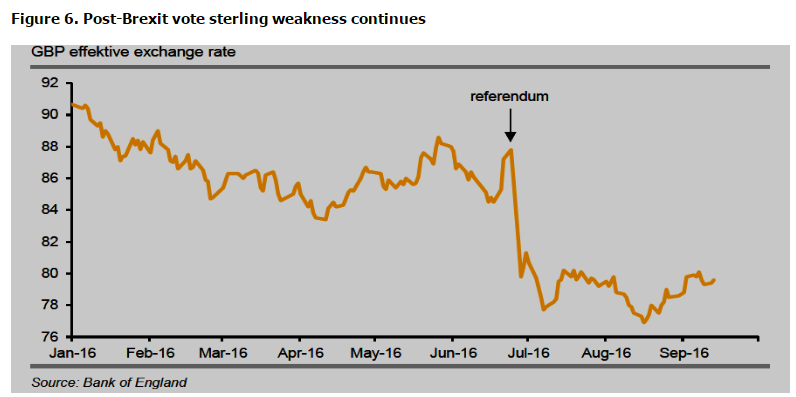

The pound sterling lost almost 10% in value after the referendum result was announced, by 16% since mid-November 2015 and has not recovered since. Of course, the Bank of England's measures announced in August have also contributed to avoiding a shock wave in the face of great uncertainty. Still, the uncertainty surrounding the timing and the "type of Brexit" to be implemented, given the size of the current account deficit and the uncertainty around the continuation of foreign capital inflows, poses a big risk for the pound and further depreciation is expected, albeit, at a somewhat lesser extent than originally expected. Sterling investors thus face continuing pain for the foreseeable future. As a result, an expected range for the euro against the pound by year-end is between 0.83-0.90 (Figures 5, 6).

Yen

My personal view is that the most challenging currency the months ahead is the yen! Monetary stimulus has not achieved a lasting weakening of Japan's currency and the reflation of the economy is still away. Since Bank of Japan's last policy meeting, the new name of the game for its monetary policy is "QQE (qualitative quantitative easing) with yield curve control".

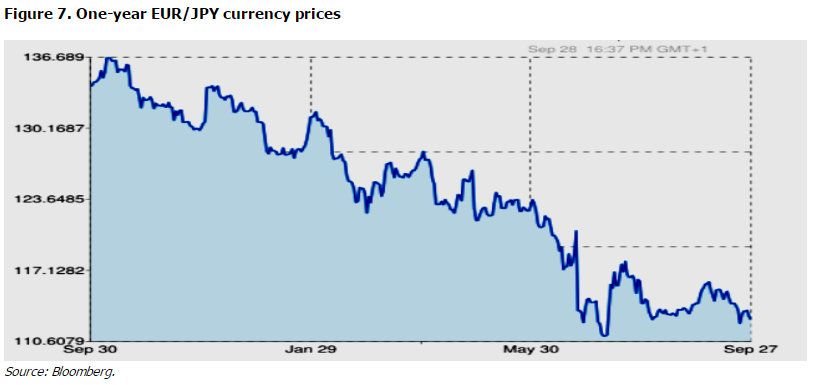

Although the Bank of Japan kept interest rates unchanged at minus 0.1%, it announced a new framework with two main elements: the first is a pledge to cap 10-year government bond yields at 0.0%. Second, the Bank of Japan has pledged to continue buying assets until inflation "exceeds the price stability target of 2% and stays above the target in a stable manner". This is a new inflation overshooting commitment. Sounds to me a bit optimistic! An expected range for the EUR/JPY exchange rate by year-end is between 1.10-1.25 (see Figure 7).

· Equities

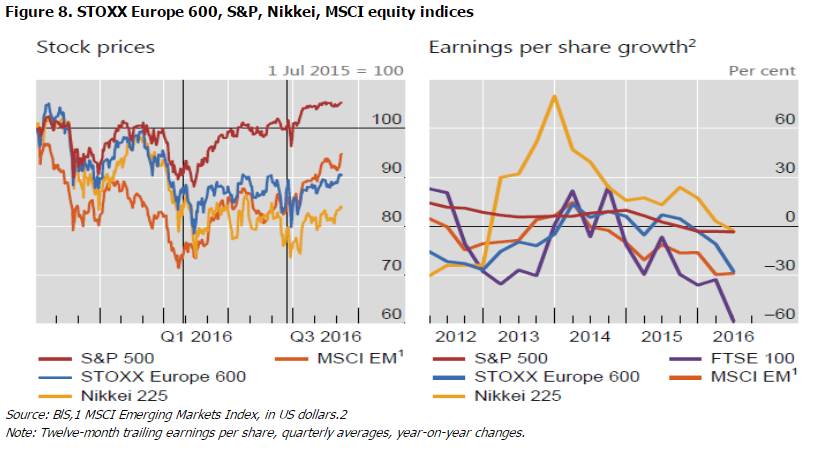

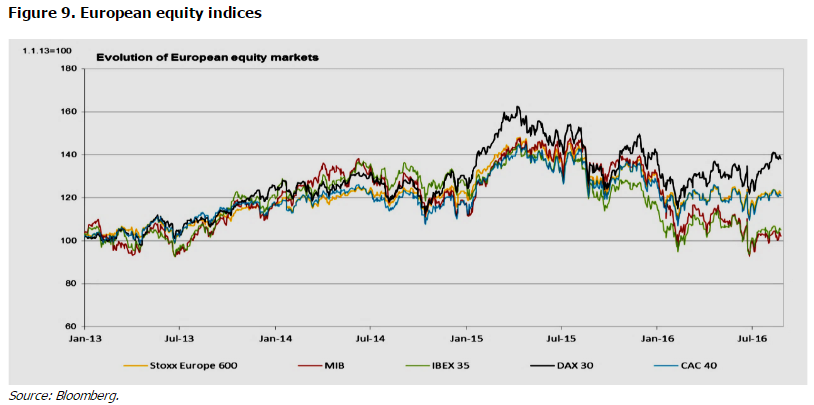

Global equity markets have also recovered from Brexit and by mid-July, despite flagging earnings, stock markets in the US had broken through all-time highs, while the emerging market equities experiencing strong performance, returning to levels last seen a year earlier. All three main equity indices (S&P 500, Dow Jones, Nasdaq) reached all-time highs around the middle of August. European stock exchanges have recouped the losses suffered as a result of the Brexit vote (Figures 8, 9). However, recent developments surrounding the banking system, clearly add to uncertainties making equity markets outlook rather foggy! Taking into account the recent Deutsche Bank's troubles, I just wanted to mention that it is among the systemically most important banks in the world and the IMF concluded in its June Financial Stability assessment that it made the largest net contribution to global systemic risk. However, there are some reassuring factors. The global financial system is now much better capitalised and able to withstand shocks than it was in 2008. Even if the worse came to worst, it seems likely that the German Government would provide a bailout. And the German Government could easily afford a bail-out without raising concerns about its own finances.

· Bonds

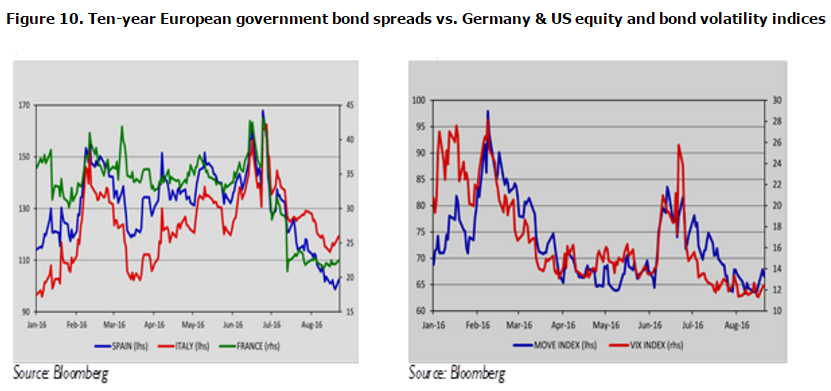

Finally, on fixed income, core bond yields continued to probe historical lows after Brexit. More precisely, German 10-year bond yields hover in the area of -0.07% and the peripheral bonds have been the main beneficiaries of the hunt-for-yield environment along with the benign risk environment as reflected in declining volatilities across asset classes. Also, the US government bond yields declined further near 1.50%, mainly due to the Fed's delay in raising rates (Figure 10). Thus, markets went through the Brexit vote with little or no disruption to functioning with ample liquidity.

2. Implications of Brexit for central banks

a. Less monetary policy divergence

The Brexit vote triggered a broad-based reassessment of the future path of monetary policy globally. With improving headline growth still perceived as fragile in most advanced economies, and inflation still persistently low, the distinct response from major central banks to the Brexit uncertainty can be described as dovish: policy rates would stay "low for longer".

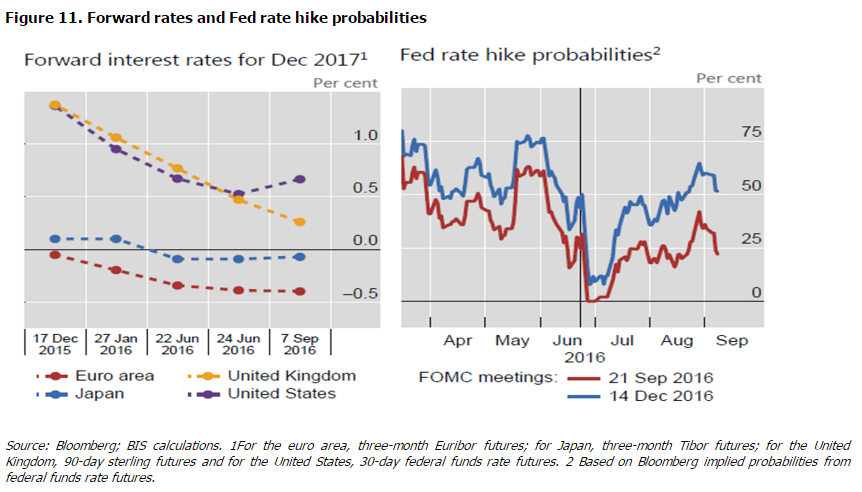

Bank of England

The Bank of England cut the policy rate by 25 basis points (it is now 0.25%), and expanded the government bond purchase scheme by £60 billion, bringing the total to £435 billion. It also established a new corporate bond purchase program of £10 billion, and launched a new Term Funding Scheme that will provide funding for banks at rates close to the monetary policy rate. Forward interest rates for December 2017 quickly dropped to the new level of the policy rate, reflecting the view that a quick policy reversal was not expected (Figure 11).The prospect of further Bank of England policy easing in the coming months cannot be ruled out, as the minutes from the September 14th Bank of England MPC meeting revealed that the majority of the policy members are expected to support a further rate cut in the course of the year if the UK's economic outlook is judged to be "broadly consistent" with August projections (i.e. GDP growth is expected to slow to 0.1% quarter-on-quarter in Q3 2016 from 0.6% quarter-on-quarter in Q2 2016).

Federal Reserve

Following the Brexit shock in the US, a 2016 rate rise is not fully priced in the market with the implied probability of a Fed rate hike in December 2016 to be around 55% today (Figure 11, right-hand panel). In addition, the Fed at the September policy meeting cut the longer-run federal funds rate to 2.9% from 3.0% previously, while, based on the updated dot-pot, the median path of appropriate monetary policy for 2017 shifted in a dovish direction.

Bank of Japan

The Bank of Japan in its last policy meeting launched a novel kind of monetary easing as it set a cap on 10-year bond yields and vowed to take action to overshoot its 2% inflation target. Its decision demonstrates that central bankers are still willing to experiment with new monetary policy ideas, as inflation remains too low. Some observers characterised this shift as probably the biggest innovation in monetary policy since the introduction of negative deposit rates by the Danish central bank in the summer of 2012! But what actually does this new monetary policy framework in Japan mean (we may call it long-term interest rate targeting) and what are its implications?

There are two main issues here under consideration: firstly, this is another policy dilemma of the nature "prices vs. quantities" and secondly, it is a further accommodative monetary policy stance, but with an asterisk. Starting with the first, it seems that the role of quantities such as the monetary base is downgraded and becomes much less important than before. In other words, instead of committing to buy a fixed amount at a market-determined rate, the Bank of Japan will buy a potentially unlimited amount at a pre-determined rate (price).

It is true that the package of measures allows a lot of flexibility for the Bank of Japan to determine long-term rates (in addition to short-term base rates), but also raises many questions. For one thing, the Bank of Japan is now attempting to control both prices and quantities, which is simply not feasible! On the other hand, fixing 10-year rates at 0% may require to buy whatever quantity of bonds necessary to deliver rate stability, which may mean buying more or less than its target pace of ¥80 trillion per year. In other words, the Bank of Japan could reduce the pace of QE purchases in the future if it thinks it can achieve its yield target with fewer bond purchases, for example in a scenario where markets perceive the Bank of Japan's yield target as credible or yields turn negative! Any potential reduction in bond purchases would be equivalent to tapering. It is exactly this built-in tapering mechanism that explains the asterisk I mentioned above. In other words, it is conceivable in the future that the Bank of Japan could be forced to sell JGBs if markets challenge the central bank by pushing the 10-year JGB yield well below its 0% target. This selling would be equivalent to a reversal of QE, it could be self-defeating in the case where inflation is still too low.

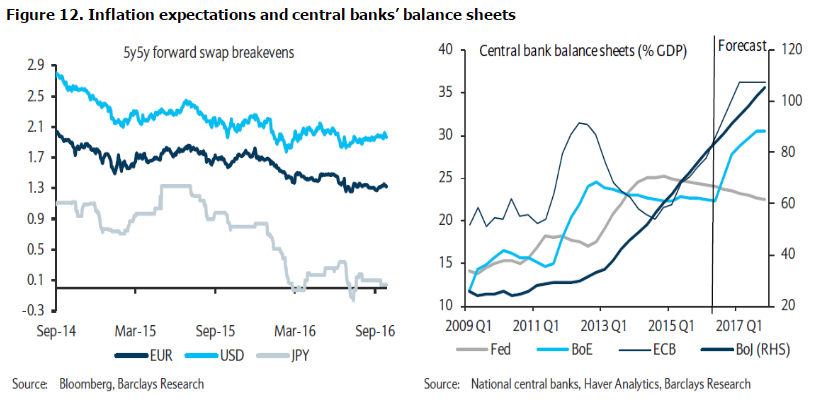

ECB

At its latest GC meeting, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will extend its QE programme beyond March 2017 if needed. Looking forward, markets expect the eurozone economy to need more stimulus from the ECB as the gap between current headline inflation (0.2% year-to-date average), the ECB's inflation forecasts (1.2% in 2017, 1.6% in 2018) and its higher target justify further policy easing (Figure 12).

So far, there is some encouraging evidence from the ECB's ongoing QE programme.

In more detail:

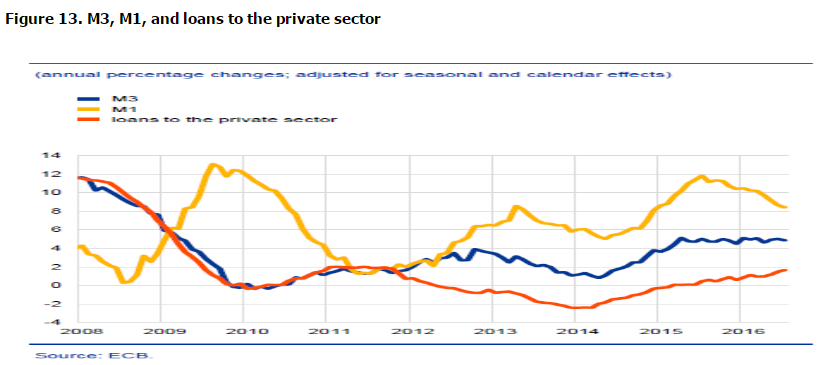

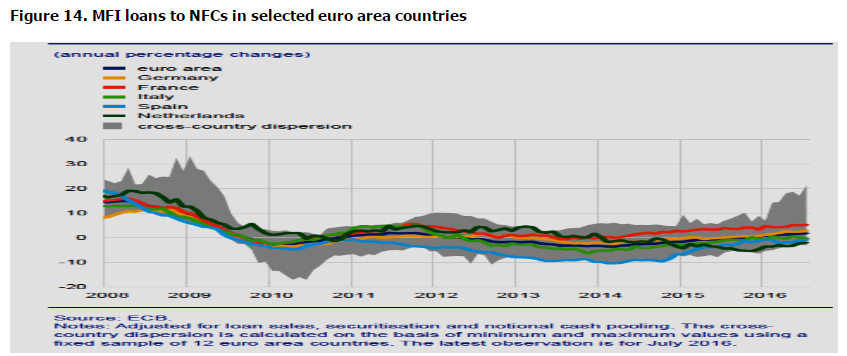

Banking credit channel

Loan growth continued to recover gradually as the annual growth rate of the monetary financial institutions (MFIs) loans to the private sector (adjusted for loan sales, securitisation and notional cash pooling) is expected to increase further in the second quarter of 2016 and in July (see Figure 13), particularly for private companies (non-financial corporations or NFCs in ECB jargon) (see Figure 14) which recovered substantially from the trough of the first quarter of 2014. Lending to companies grew by 1.9% year-o-year, while household lending grew by 1.8%.

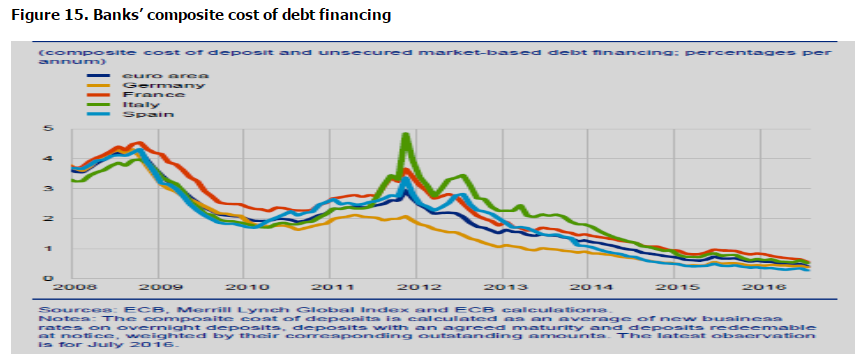

A significant improvement has also been observed in Eurosystem banks' composite cost of debt financing, which declined in July to a new historical low, after broadly stabilising in the second quarter of 2016 (see Figure 15).

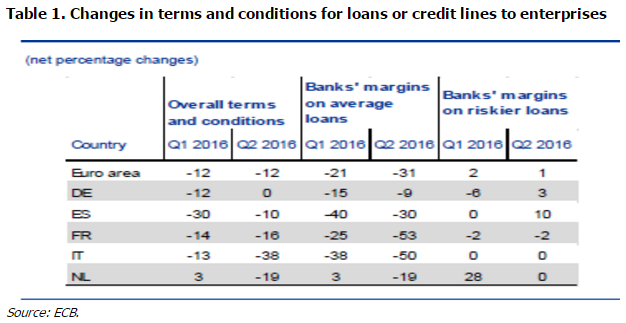

Also, banks reported a further net easing of credit standards on loans to enterprises in the second quarter of 2016, suggesting a continued improvement in financing conditions for corporate loans. Across the largest euro area countries, overall terms and conditions eased across all larger countries except for Germany (Table 1). In most of the large euro area countries, in particular, France and Italy, banks continued to report a narrowing of margins on average loans in net terms. Margins on riskier loans widened in net terms in Spain and Germany.

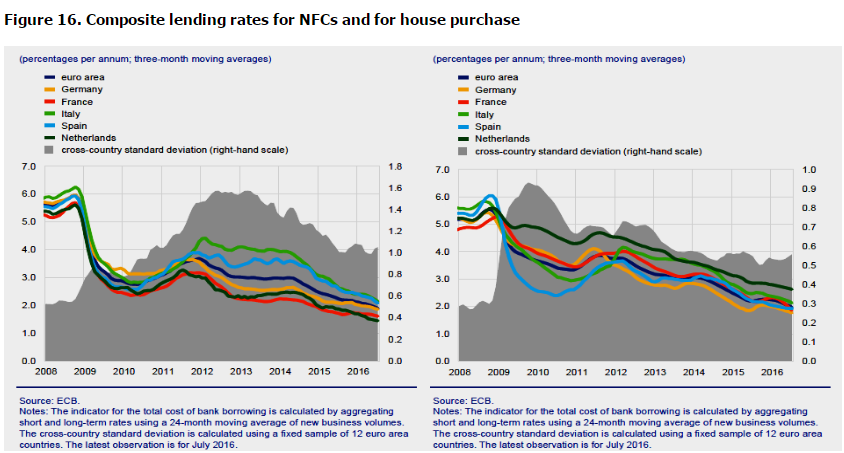

Furthermore, bank lending rates for the private sector remained on a downward trend in the second quarter of 2016 and in July (see Figure 16). Composite lending rates for NFCs and households have decreased by significantly more than market reference rates since June 2014, and between May 2014 and July 2016, composite lending rates on loans to euro area NFCs (corporate loans) and households (i.e. mortgages) fell by around 100 basis points. The reduction in bank lending rates was especially strong in vulnerable euro area countries, indicating reducing fragmentation in euro area financial markets. Over the same period, the spread between interest rates charged on very small loans (loans of up to €0.25 million) and those charged on large loans (loans of above €1 million) in the euro area followed a downward trend. This indicates that small- and medium-sized enterprises have generally been benefiting to a greater extent than large companies from the decline in lending rates.

b. QE vs. negative rates

Staying in the eurozone and taking as a given fact that we will move towards more accommodative monetary policy in the months ahead, a more open question is: which policy instrument will be used? More QE or further negative rates? This is the essence of the monetary policy debate in the eurozone today.

Clearly, there are limits to persistent negative rates, namely the underlying question is how far and for how long they can actually go. There are a number of concerns including banks' profitability, how negative rates may act as an anaesthetic to euro area governments especially in the euro area's southern periphery, taking into account that the fiscal space gained from lower debt service costs may result in a slower implementation of necessary fiscal and structural reforms.

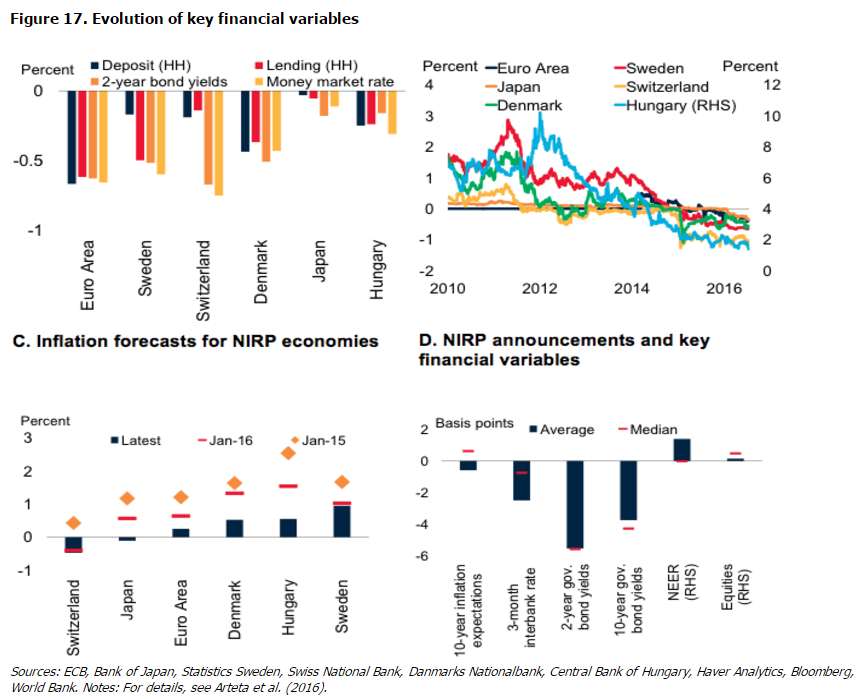

Policy rate cuts to negative levels have generally been reflected in corresponding declines in money market rates and short-term government bond yields (see Figure 17). In turn, the fall in bank wholesale funding costs has helped lower lending rates, but to varying degrees across countries. The decline in rates on new loans has been particularly notable in the eurozone (Viñals et al. 2016, Jobst and Lin 2016). Inflation expectations have continued to decline in most economies with negative interest rate policies (also known as NIRP countries).

In addition, there are concerns about the political and institutional feasibility of negative rates as their long-term effects are still unknown. Most importantly, their effectiveness is put under question during a recession, if this were to emerge in the near future.

I would personally, in my professorial hat, prefer to see more QE rather than further negative rates. If this is the case, the next question is where could more QE in the eurozone come from? In other words, does the ECB have the tools for more QE stimulus?

Well, there are several options. From changing the parameters of the current QE programme like, for instance, buying bonds below the deposit rate, increasing the 33% issue share limit, dropping the capital key allocation, or even adding new securities to the pool of eligible assets such as bank bonds or equity.

Let me now turn to the effects of Brexit on the dynamics of European integration and indeed offer a southern point of view and, more particularly, make five points from the South on the Brexit vote.

3. A Southern view on Brexit's implications for the EU1

The European Union is currently facing crises on multiple fronts (anaemic growth, high unemployment, persistently low inflation close to deflation, a debt crisis, an ongoing migrant crisis), but Brexit represents the biggest medium- to long-term challenge of all. I will focus here on a couple of rather important points.

Euroscepticism is now a strong sentiment in Europe. Populist, authoritarian parties are in government or in a ruling coalition in nine (9) countries of the EU. This is an alarming figure. Referendums in Italy and Hungary, and national elections next year in the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, France and Germany, are expected to reinforce this eurosceptic mood.

Beyond the obvious economic concerns which triggered the UK vote to leave the EU, everyone agrees that the EU needs to address the issue of its democratic deficit and accountability.

In addition, it has long been argued that the European Union remains a 'market without a state'. This quote perhaps summarises the debate on European integration over the last 40 years at least. The most frequent complaint regarding the way the EU works is that it is governed by an elite of unelected technocrats through several independent European institutions and bodies (including the ECB).

In light of the above issues of democratic deficit and accountability, Europeans are increasingly disenchanted with the EU, as shown by the rise of populist, authoritarian parties. Support for populist political parties with eurosceptic credentials has been rising, that is, parties which are by nature more Eurosceptic and less oriented towards reforms, which of course the South badly needs. As a result, this is a major downside risk to debt sustainability in this part of the euro area.

For continental Europe, Brexit represents a shock to the institutions and norms that underpin markets, albeit different from the euro break-up fears of 2012, the global financial crisis of 2008 or the bursting of the high-tech bubble of 2001. The origins of previous financial crises can be located in multiple factors that are linked with the financial system and the economic cycle, respectively. The risk today is not financial contagion, like in 2008. Instead, it represents a contagious political development. No matter whether we have a full-blown or a light Brexit, the political risk for the continent is that referendums may mushroom across Europe in a tug-of-war between populist forces and the political establishment and elites. Brexit has the potential to unleash centrifugal forces, leading perhaps to a breakup of the euro, especially if such a referendum were to be held this time in a major eurozone country. Perhaps such a referendum is more likely in a southern eurozone country.

Thank you very much for your attention.

1 For a more detailed account, see my speech (September 2016) at Banca d' Italia, Rome.