Following the imprint of the ECB's asset purchase programme on global bond and deposit flows

We trace the imprint of the ECB's expanded asset purchase programme (APP) on international bond portfolios and euro-denominated deposits. Our analysis suggests that non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) located outside the euro area sold large volumes of euro area government bonds and kept a substantial fraction of the proceeds as euro-denominated deposits, primarily in UK-resident banks. Since the APP's modalities did not allow the NBFIs to engage directly with the Eurosystem, their deposits left an international trail of euro-denominated claims. Our findings highlight the role of the United Kingdom as a gateway to the euro area financial system for investors outside the euro area.1

JEL classification: E50, E52, F30, F40.

Since its launch 20 years ago, the euro has consolidated its role as a major currency in the international financial system, second only to the US dollar (Chinn and Frankel (2008), ECB (2018)). Monetary policy actions undertaken by the ECB can thus have consequences beyond the immediate borders of its currency area.

In this special feature, we attempt to piece together evidence from multiple international data sets to trace the imprints left by the ECB's expanded asset purchase programme (APP) on the international financial system. Concretely, we document notable shifts in euro-denominated bonds and deposits between the euro area and the rest of the world during the period associated with the ECB's APP. Our findings shed light on the channels through which the APP interacted with the global financial system.

A distinctive feature of the ECB's APP was that investors outside the euro area were very active sellers of euro area government bonds to the ECB (Adalid and Palligkinis (2016), ECB (2016, 2017), Koijen et al (2017), Cœuré (2018)). They accounted for roughly 50% of all APP bond sales. The asset purchase programmes conducted by other major central banks elicited much less involvement on the part of non-resident investors (Carpenter et al (2015), Joyce et al (2017), Hogen and Saito (2014)).

Key takeaways

- Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) located outside the euro area were active as sellers of euro area bonds during the ECB's expanded asset purchase programme (APP).

- Our analysis suggests that non-euro area NBFIs retained a substantial fraction of their bond sale proceeds as euro-denominated deposits in banks outside the euro area.

- Banks located in the United Kingdom and their euro area affiliates were the main facilitators of the APP bond sales by non-euro area investors.

The evidence suggests that the non-euro area APP sellers of euro area bonds retained a large fraction of their bond sale proceeds as euro-denominated deposits, rather than immediately repatriating the proceeds or reinvesting them in other bonds. UK-based investors, for instance, appear to have retained roughly a fifth of the bond sale proceeds as euro-denominated deposits.

Our analysis also highlights the key role of the United Kingdom as the main gateway to the euro area banking system for non-euro area investors during the ECB's APP. Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) located in the United Kingdom were both the largest non-resident sellers of euro area bonds during the APP period and the largest contributors to the concurrent increase in euro-dominated deposits outside the euro area.2 Furthermore, the majority of those deposits were with banks in the United Kingdom, which, together with their euro area affiliates, appear to have been the main facilitators of the APP bond sales by non-euro area investors, and the conduits to the Eurosystem.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. In the following section, we provide a stylised overview of the APP's imprint on the global financial system. We then present a "before and after" picture of the impact of the asset purchase programme, beginning with the key non-euro area bondholders on the eve of the ECB's expanded APP. Next, we track the evolution of non-euro area investors' portfolio allocations during the ECB's APP period. We go on to link these non-resident portfolio choices to the dynamics of international euro-denominated deposits, making use of the enhanced BIS locational banking statistics (LBS). We conclude by highlighting the policy relevance of our insights and posing questions for further research.

Some simple balance sheet arithmetic

We start with the following stylised example of how the ECB's APP purchases can impact on the balance sheets of the key protagonists involved in the APP (Graph 1). As a large share of euro area government securities were owned by non-euro area investors prior to the start of the APP, we consider a case in which the holder of an APP-eligible security is an NBFI located outside the euro area - for example, in the United Kingdom.

Suppose that, following the launch of the asset purchase programme, the UK investor opts to sell its holdings of euro area government securities. Since, due to the technical modalities of the APP, the NBFI cannot engage directly with the Eurosystem, it has to accept the Eurosystem bid through a bank (which is assumed to be in the United Kingdom for this example). The Eurosystem credits the bank's affiliate in the euro area with the sale proceeds in the form of central bank reserves (Graph 1, arrow 1). The affiliate in the euro area credits the bank in the United Kingdom with a within-banking group claim (arrow 2). In turn, the bank in the United Kingdom credits the selling NBFI with a euro-denominated deposit (arrow 3).

Following the sale of its government securities, the non-euro area NBFI in the above example will have several options for the proceeds. First, it can opt to rebalance its portfolio towards higher-yielding euro-denominated assets (for example, non-APP-eligible euro- denominated public sector bonds or corporate bonds). Second, the NBFI can swap the euros into, say, US dollars and invest in US dollar bonds on a hedged basis. In this case, the far leg of the swap will leave a forward sale of dollars against euros. Third, the NBFI can close its euro position in order to invest in assets denominated in a different currency (eg the US dollar). Fourth, the NBFI could keep the euro-denominated deposits.

The closest substitutes to the NBFI's previous position would be the first two options. According to standard portfolio choice models, the first option would be seen as the most likely outcome. If so, the impact will be consistent with the portfolio rebalancing channel of unconventional monetary policy (Dunne et al (2015), Carpenter et al (2015), Joyce et al (2017)). The portfolio rebalancing channel is frequently considered to be the most effective channel through which central bank asset purchases impact the real economy (Joyce et al (2012)). Greater demand for higher-risk assets, whether of longer duration or with more credit risk, increases their prices and lowers their yields. Higher asset prices increase the wealth of investors, which should boost their spending. Falling bond yields also reduce the borrowing costs for other bond issuers (eg non-financial corporates). This could spur investment, and thereby improve the overall prospects for economic growth.

Nevertheless, as we find in the next section, a substantial fraction of the APP- generated deposits of non-euro area investors may have been "sticky" in a certain sense. That is, we find that NBFIs located in the United Kingdom and in other countries outside the euro area that sold euro area securities during the APP period increased their holdings of euro-denominated deposits in banks located in the United Kingdom. This suggests that a substantial portion of the APP bond sale proceeds was retained in that form.3

Further reading

Major non-resident bondholders prior to the APP

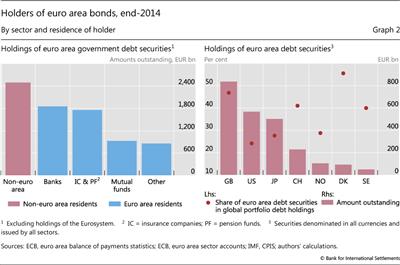

On the eve of the ECB's expansion of the APP to include public sector securities, the euro area government bond market was characterised by significant, although not overwhelming, regional bias. As of end-2014, the majority of investors in euro area government securities unsurprisingly resided in the euro area (Graph 2, left-hand panel, blue bars).4 Financial institutions - namely banks, asset managers, insurance companies and pension funds - were the primary holders of euro area government securities. Nevertheless, non-euro area investors still held almost a third of outstanding euro area government securities (left-hand panel, red bar).

The IMF's Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) sheds light on the distribution of non-euro area investors' holdings of euro area debt securities.5 These data suggest that investors from only a few countries accounted for most of the euro area bonds held outside the euro area on the eve of the ECB's expanded APP (Graph 2, right-hand panel, red bars). Investors from only seven countries - Denmark, Japan, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States - accounted for close to 90% (or €2.4 trillion) of all non-euro area investors' holdings. Investors based (but not necessarily headquartered) in the United Kingdom alone held close to a third of those securities.6

These holdings represented a significant proportion of the international portfolios of investors located in countries near the euro area (Graph 2, right-hand panel, red dots). This pattern is consistent with a gravity model of international diversification (Portes and Rey (2005), Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2008)). The portfolio shares of euro area securities were highest for Denmark (56%) and the United Kingdom (47%). Switzerland (41%) and Sweden (40%) were not far behind. The respective shares for investors in Norway (29%), Japan (28%) and the United States (24%) were also considerable.

NBFIs owned the majority of the non-resident holdings of euro area bonds. NBFIs resident in the United Kingdom alone held €560 billion worth of euro area bonds on the eve of the ECB's APP, accounting for two thirds of the euro area bond holdings of all UK residents and over a fifth of the euro area bond holdings of all investors outside the euro area.

The large share of euro area bonds held by investors based in the United Kingdom underlines its role as a gateway to the euro area financial system for non-euro area investors. To a large degree, it reflects the United Kingdom's role in hosting an international financial centre (Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018)).7 Importantly, UK-resident NBFIs include the investment management subsidiaries of financial firms headquartered in other countries.

Tracking cross-border bond flows during the ECB's APP

In the first quarter of 2015, the ECB significantly expanded the scale of its APP by starting to acquire euro area government bonds and public sector bodies' bonds under the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP).8 The intensity of the targeted pace of APP purchases fluctuated considerably - from a high of €80 billion a month between April 2016 and March 2017 to a low of €15 billion a month between October and December 2018. At the cessation of net purchases at end-December 2018, Eurosystem holdings of debt securities under the APP had reached €2.6 trillion, with holdings of public sector securities at €2.1 trillion, or 82% of the total.9 In this section, we examine the dynamics of non-euro area investors' holdings of euro area debt securities during the APP.

Non-euro area investors sold large amounts of euro area government bonds into the Eurosystem bid. In fact, these investors accounted for approximately half of net sales during this period (ECB (2017)). This represented a sharp reversal of the trend from the pre-APP period, when non-euro area investors were net purchasers.

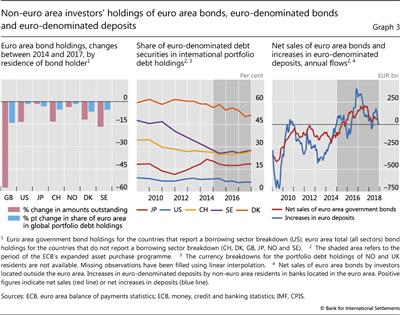

Investors located in the United Kingdom were the most active sellers located outside the euro area (Graph 3, left-hand panel, red bars).10 Their portfolio holdings of euro area debt contracted by more than 50% between end-2014 and end-2017.11 The share of the euro area in the global debt portfolio of UK-based investors fell from 47% at end-2014 to 33% at end-2017 (left-hand panel, blue bars). Over the same time period, the positions of investors in Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland also fell considerably.12 Holdings of investors in Japan fell somewhat less in percentage point terms, but from a much larger initial stock. The upward slope to the euro area yield curve and the flattening of the US yield curve made hedged Japanese investment in euro area government bonds relatively attractive, even with low yields.

Among individual sectors, NBFIs sold the most euro area bonds during the period of the ECB's APP. Our estimates suggest that NBFIs resident in the United Kingdom cut their holdings of euro area debt securities by approximately €300 billion between end-2014 and end-2017. NBFIs resident in Denmark and Sweden also reduced their holdings of euro area bonds considerably.

In contrast to the share of bonds issued by euro area residents, the share of euro-denominated bonds remained relatively stable for most major investor countries outside the euro area during the APP period (Graph 3, centre panel). This finding suggests that those investors purchased euro-denominated bonds issued by non-euro area residents. This is in line with the surge in euro-denominated ("reverse yankee") bond issuance by US (and other non-euro area) corporates that occurred during the APP period (Borio et al (2016)).13

Tracing cross-border euro deposits during the ECB's APP

The net sales of euro area securities by non-euro area investors during the APP have gone hand in hand with a significant rise in non-euro area-sourced euro-denominated deposits in euro area-resident banks (Graph 3, right-hand panel). The simultaneous increase in the two series is not coincidental. It most likely has two drivers. First, as illustrated in Graph 1, the modalities of the APP necessitated that sales by non-euro area investors be settled through banks in the euro area (via central bank reserves). This generated new cross-border positions between banks located outside the euro area and their affiliates inside the euro area. Second, non-euro area NBFIs considerably increased their euro deposits during the APP period, suggesting that they are likely to have retained a non- negligible fraction of their bond sale proceeds in the form of euro-denominated deposits.

In this section, we combine the enhanced BIS LBS with the IMF CPIS data set to link the evolution of cross-border bond flows with the international flows of euro-denominated deposits.14 In the process, we identify the residence and the sector of the most important participants and quantify their respective contributions.

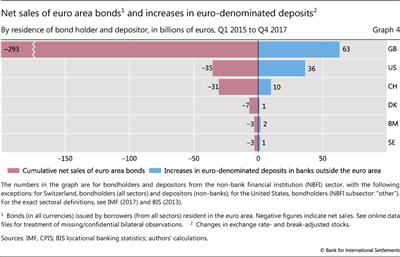

The investors that were the most active sellers of euro area bonds during the period of the ECB's APP were from sectors and countries that were also the main drivers of the concurrent sizeable increases in euro-denominated deposits in banks outside the euro area (Graph 4).15 Most notably, NBFIs located in the United Kingdom reported a large contraction in their holdings of euro area bonds (Graph 4, red bars) and a sizeable increase in their euro-denominated deposits (blue bars). The respective bond and deposit holdings of NBFIs in several other countries exhibited a broadly similar pattern, although the amounts involved were much smaller.16

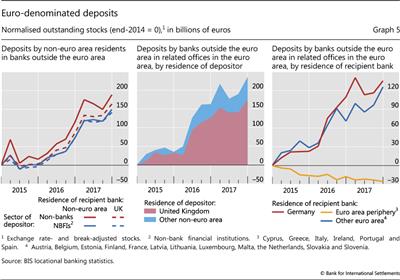

The increase in euro- denominated deposits outside the euro area between end-2014 and end-2017 was substantial (Graph 5, left-hand panel). At approximately €190 billion, it amounted to almost 20% of the total volume of APP public sector securities sold by non-euro area investors. NBFIs accounted for the majority of the expansion in euro-denominated deposits. Most of those were placed in UK-resident banks.17

The substantial increase in the euro-denominated deposit liabilities of banks located outside the euro area was closely matched by a simultaneous, similarly sized expansion in their euro-denominated claims on related offices in the euro area (Graph 5, centre panel). The latter series grew by €236 billion between the start of 2015 and the end of 2017. The majority of the surge took place between Q2 2016 and Q1 2017, which was the period when the pace of purchases (€80 billion per month) was at its highest.

Banks located in the United Kingdom were the main drivers of the expansion in euro-denominated deposits between affiliated offices of the same banking organisation during the APP period (Graph 5, centre panel, red area). Roughly three quarters (or €176 billion) of the overall expansion was reported by banks located in the United Kingdom. This total also reflects the role played by banking groups headquartered outside the United Kingdom, underscoring the role of London as a global banking centre (McCauley et al (2017)). Within-group deposits from all other non-euro area jurisdictions followed a similar pattern (centre panel, blue area), but rose by a smaller amount (€60 billion). The latter comparison highlights the important role of the United Kingdom as a financial gateway to the euro area.

The main recipients of the APP-induced increase in euro-denominated deposits from outside the euro area were banks located in the traditional financial gateways inside the euro area. Banks in Germany alone received €136 billion of additional deposits from their related offices outside the euro area (Graph 5, right-hand panel). The corresponding increase for banks in other (non-periphery) euro area countries was €126 billion. By contrast, deposits into related offices in the euro area periphery countries (Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain) contracted by €26 billion.18

Lessons learned and questions for further research

In this special feature, we have combined information from multiple sources in an attempt to trace the imprint left by the ECB's APP on international bond portfolios and euro-denominated deposits.

We find that NBFIs located in the United Kingdom and in other countries outside the euro area sold large volumes of euro area bonds during the ECB's APP. Given that the NBFIs could not engage directly with the Eurosystem due to the technical framework of the operations, the "sticky" portion of their APP proceeds left a trail in the global financial system in the form of a chain of euro-denominated deposits. The substantial rise in the NBFIs' euro-denominated deposits in banks outside the euro area was mirrored by contemporaneous expansions in those banks' deposits in their euro area affiliates as well as by corresponding increases in those affiliates' reserves at the Eurosystem. We argue that, taken together, the above pieces of empirical evidence suggest that non-euro area NBFIs kept a substantial fraction of their APP bond sale proceeds as euro-denominated deposits at banks outside the euro area.

Our study highlights the key role of the United Kingdom as a gateway to the euro area financial system for investors outside the euro area. During the APP period, NBFIs located in the United Kingdom were the most active non-resident sellers of euro area bonds and the main drivers of the increase in euro-denominated deposits. Moreover, banks in the United Kingdom acted as the main facilitators of the APP bond sales by non-euro area investors.

Our findings highlight possible channels through which unconventional monetary policy can have significant cross-border effects. In a complementary study using micro data (Avdjiev et al (2019)), controlling for global factors and bank-specific characteristics, we provide additional empirical support for the effects of the ECB's APP on non-euro area-sourced deposits with euro area banks. Avdjiev et al (2019) also document how banks in the euro area that received the funds not only increased their excess reserves with the Eurosystem but also expanded their lending to borrowers outside the euro area. Continued monitoring of these cross-border positions and transactions would allow a better assessment of the possible economic impact of the completion of net asset purchases by the Eurosystem as of December 2018.

Our exploration of the international dimension of the ECB's APP also raises questions for further research on unconventional monetary policy measures. Understanding the mechanisms of unconventional monetary policy may provide insights as to how investors will react to its unwinding. Is it likely that, in contrast to more standard forms of stimulus, there will be asymmetry between the effects of the implementation and the unwinding of unconventional monetary policy? And, does the behaviour of global investors depend on the degree of divergence among the monetary policy stances of central banks in charge of major reserve currencies?

References

Adalid, R and S Palligkinis (2016): "Sectoral sales of government securities during the ECB's asset purchase programme", mimeo.

Auer, R and B Bogdanova (2017): "What is driving the renewed increase of TARGET2 balances?", BIS Quarterly Review, March, pp 7- 8.

Avdjiev, S, M Everett, L Gambacorta and H S Shin (2019): "An international bank lending channel during quantitative easing: a view from the euro area", mimeo.

Avdjiev, S, P McGuire and P Wooldridge (2015): "Enhanced data to analyse international banking", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 53-68.

Bank for International Settlements (2013): Guidelines for reporting the BIS international banking statistics: version incorporating Stage 1 and Stage 2 enhancements recommended by the CGFS, March.

Borio, C, R McCauley, P McGuire and V Sushko (2016): "Covered interest parity lost: understanding the cross-currency basis", BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp 45-64.

Carpenter, S, S Demiralp, J Ihrig and E Klee (2015): "Analyzing Federal Reserve asset purchases: from whom does the Fed buy?", Journal of Banking and Finance, vol 52, pp 230-44.

Cecchetti, S, R McCauley and P McGuire (2012): "Interpreting TARGET2 balances", BIS Working Papers, no 393, December.

Chinn, M and J Frankel (2008): "Why the euro will rival the dollar", International Finance, vol 11, no 1, pp 49-73.

Cœuré, B (2018): "The international dimension of the ECB's asset purchase programme: an update", speech at a conference on Exiting unconventional monetary policies, Paris, 26 October.

Dunne, P, M Everett and R Stuart (2015): "The expanded asset purchase programme - what, why and how of euro area QE", Central Bank of Ireland, Quarterly Bulletin, no 3.

Eisenschmidt, J, D Kedan, M Schmitz, R Adalid and P Papsdorf (2017): "The Eurosystem's asset purchase programme and TARGET balances", European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series, no 196.

European Central Bank (2016): "TARGET balances and the asset purchase programme", Economic Bulletin, issue 7, box 2.

--- (2017): "Which sectors sold the government securities purchased by the Eurosystem?", Economic Bulletin, issue 4, box 6.

--- (2018): The international role of the euro, Interim Report, June.

Hartmann, P and F Smets (2018): "The first twenty years of the European Central Bank: monetary policy", European Central Bank, Working Paper Series, no 2219.

Hogen, Y and M Saito (2014): "Portfolio rebalancing following the Bank of Japan's government bond purchases: empirical analysis using data on bank loans and investment flows", Bank of Japan Research Papers, 14-06 -19.

International Monetary Fund (2009): Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual.

--- (2017): Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey Guide.

Joyce, M, Z Liu and I Tonks (2017): "Institutional investors and the QE portfolio balance channel", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol 49, no 6, September, pp 1225-46.

Joyce, M, D Miles, A Scott and D Vayanos (2012): "Quantitative easing and unconventional monetary policy - an introduction", Economic Journal, vol 122, no 564, November, pp 271-88.

Koijen, R, F Koulischer, B Nguyen and M Yogo (2017): "Euro-area quantitative easing and portfolio rebalancing", American Economic Review, vol 107, no 5, May, pp 621-7.

Lane, P and G Milesi-Ferretti (2008): "International investment patterns", The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol 90, no 3, August, pp 538-49.

--- (2018): "The external wealth of nations revisited: international financial integration in the aftermath of the global financial crisis", IMF Economic Review, vol 66, no 1, pp 189-222.

Maggiori, M, B Neiman and J Schreger (2018): "International currencies and capital allocation", NBER Working Papers, no 24673, May.

McCauley, R, A Bénétrix, P McGuire and G von Peter (2017): "Financial deglobalisation in banking?", BIS Working Papers, no 650, June.

Portes, R and H Rey (2005): "The determinants of cross-border equity flows", Journal of International Economics, vol 65, no 2, March, pp 269-96.

1 The authors would like to thank Claudio Borio, Stijn Claessens, Benjamin Cohen, Ingo Fender, Branimir Gruić, Robert McCauley, Benoît Mojon and Gillian Phelan for helpful comments; Zuzana Filková and Deimantė Kupčiūnienė for excellent research assistance; Conor Parle and Swapan-Kumar Pradhan for excellent data assistance; and Mario Barrantes for excellent assistance with graph design. Mary Everett developed parts of this work while visiting the Bank for International Settlements under the Central Bank Research Fellowship Programme. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements, the Central Bank of Ireland or the European System of Central Banks.

2 NBFIs include non-bank entities engaged in the provision of financial services and in activities auxiliary to financial intermediation such as fund management. Examples of the entities included in this category are insurance companies, pension funds, money market funds and other financial corporations (eg investment funds, financial auxiliaries, and securities and derivatives dealers). For more details, see IMF (2009) and BIS (2013).

3 It bears emphasis that the available data do not allow us to examine whether individual bond sellers increased their deposits, but reveal only that the largest increases in euro deposits outside the euro area came from the sector-country pairs (eg NBFIs in the United Kingdom) that sold the largest volumes of euro area bonds during the APP period. This pattern is consistent with the seller retaining the deposit, and for concreteness we will phrase the finding this way, but strictly speaking the data only provide evidence of sectoral stickiness.

4 When the available data allow us to do so, we focus on euro area government securities since they represent the overwhelming majority of the ECB's APP purchases.

5 The CPIS covers bilateral country holdings of debt securities. Since not all countries report detailed bilateral sectoral breakdowns, we examine bilateral holdings of debt securities issued by all sectors for the cases where more detailed sectoral breakdowns are not available.

6 The CPIS data set is compiled on a residence basis, ie it reports the asset holdings of a creditor based on its geographical residence rather than the location of its ultimate owner.

7 Unfortunately, the existing data do not allow us to attribute the UK-resident NBFIs' holdings to their ultimate beneficial owners.

8 In March 2016, the APP was enhanced through the inclusion of euro-denominated debt securities issued by non-bank corporations resident in the euro area. Known as the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme, it commenced in June 2016 and as of end-December 2018 it accounted for just under 7% of the APP's total asset holdings.

9 In December 2018, the ECB's Governing Council announced that the principal payments from maturing securities would be reinvested for an extended period of time, past the horizon of interest rate increases. See Hartmann and Smets (2018) for a detailed discussion of the evolution of ECB non-standard monetary policy measures.

10 As mentioned above, we examine bilateral holdings of debt securities issued by all sectors, since more detailed sectoral breakdowns are not available for most countries. Nevertheless, data from the ECB balance of payments statistics reveal that almost the entire contraction in the portfolio debt liabilities of euro area residents vis-à-vis the rest of the world between end-2014 and end-2017 can be attributed to debt securities issued by the government sector.

11 We stop our empirical investigation at end-2017, due to the fact that this is the date of the latest available data points from the CPIS series we examine.

12 The reported changes in stocks from the CPIS data may have been affected by valuation effects.

13 For a detailed analysis of the determinants of the currency composition of international bonds portfolios, see Maggiori et al (2018).

14 See Avdjiev et al (2015) for a detailed description of the enhanced LBS.

15 The category "Deposits" in the BIS LBS also includes repurchase agreements (repos).

16 As noted above, the CPIS data allow us to track only the country of residence of the seller, thus ignoring the country of the ultimate investor. Hence, given the United Kingdom's role as an international financial centre, the CPIS numbers are likely to overstate the volumes of euro area bonds sold by UK-owned investors and understate the respective volumes for investors headquartered in other economies.

17 We end our empirical analysis based on the enhanced BIS LBS at end-2017 in order to match the last data point currently available in the CPIS data set.

18 The combination of the fact that banks outside the euro area primarily selected their affiliates in core euro area countries to facilitate the APP sales and the fact that banks in the euro area tend to hold reserves at their respective national central banks contributed significantly to the widening of TARGET2 balances during the implementation of the APP; see Auer and Bogdanova (2017), ECB (2016) and Eisenschmidt et al (2017). The dynamics of this latest episode differed sharply from those of the earlier episode of widening TARGET2 balances, as described by Cecchetti et al (2012).